Over the past few years, additive manufacturing – better known as 3D printing – has become a mainstream technology. Although its roots go back to the 1970s, a great deal of hype has accompanied its recent emergence among a wave of “disruptive” technologies apparently set to destroy existing business models, empower individuals and evade any kind of government control.

In a technical sense, 3D printing is certainly transformative. Users can create objects that are impossible to make using conventional “subtractive” manufacturing, and they can produce less unusual objects more quickly and cost-effectively while reducing wastage. And 3D printing’s revolutionary potential also extends to the social, economic and legal realms. In particular, low-cost 3D printing, accompanied by widespread online file-sharing of design files, may be giving rise to a post-scarcity, post-control environment in which “prosumers” have access to an abundance of information to create complicated objects in their own homes.

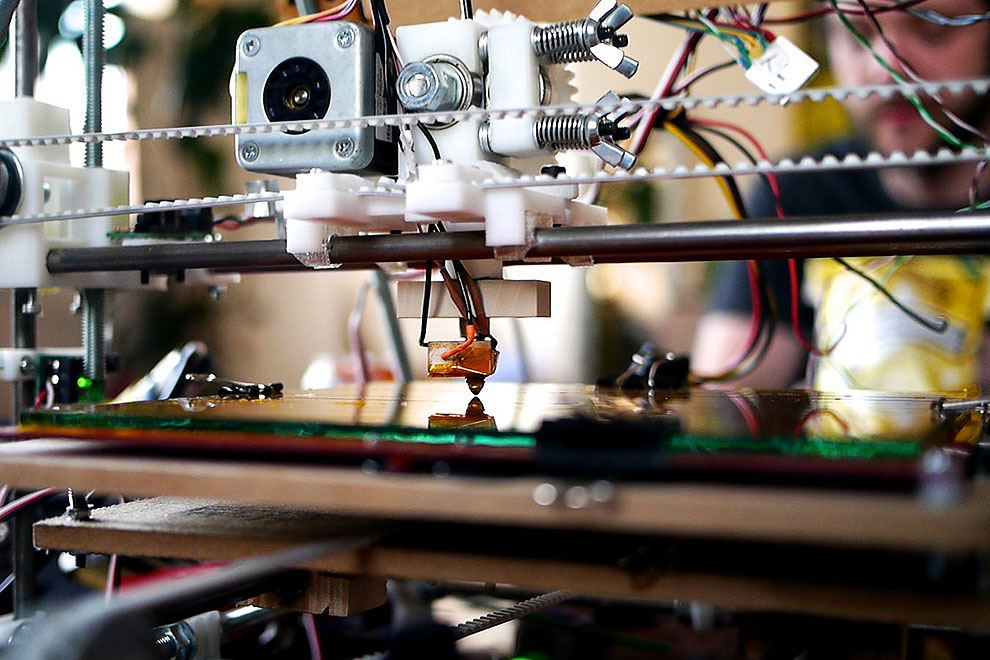

It’s true that the raw materials and energy needed by 3D printers are still subject to scarcity constraints. Yet projects such as Markus Kayser’s solar-powered 3D printer, which uses sand to print glass objects, and the Perpetual Plastic Factory, which uses discarded plastic glasses as raw material, show that the inputs need not be particularly scarce. The RepRap project even enables individuals to build their own 3D printers, and there is a strong sharing ethic – of tools, know-how and other resources – in the 3D printing hacker/maker communities.

The idea that 3D printing signals the end of bureaucratic control has its roots in the development of the 3D printed gun, the Liberator, by the open source group Defense Distributed. More of a political experiment than an expedient way to manufacture a firearm, the design’s release in 2013 led some commentators to claim that the legal and regulatory capacity of the nation-state had been fatally undermined. The proliferation of 3D printing design files, meanwhile, highlighted the technology’s challenges to intellectual property – and to the corporate business models that rest on copyright and patents.

Yet, at least in theory, existing laws and regulations do govern 3D printing and its applications. It’s more a question of how well they can be enforced. Is the decentralised nature of 3D printing too difficult to control? In fact, the fledgling consumer experience of 3D printing tells a different, more sober story.

Research so far on the popular 3D-printing design file platform Thingiverse, for example, suggests that its users tend to be protective of their own design files, despite the site’s rhetoric about sharing. A comprehensive study commissioned by Britain’s Intellectual Property Office found that while there was small-scale evidence of intellectual property infringement on 3D printing file-sharing platforms, the British businesses surveyed did not see consumer/prosumer 3D printing as posing a strong threat to their own intellectual property.

It’s also important to remember that many incumbent companies are integrating 3D printing into their own business practices or staving off competition from disruptive upstarts by partnering with existing 3D firms. US confectionery brand Hersheys announced a partnership with a major 3D printer manufacturer, 3D Systems, to launch a chocolate printer, and toy manufacturer Mattel is developing its own 3D printing offering, the Thingmaker, which will let children print their own toys at home using a custom-designed app.

Consumer take-up of 3D printers, meanwhile, seems to be lower than expected. MakerBot, a New York startup bought by Stratasys in 2013 for US$400 million, shed one in five of its employees in 2015 and has announced the closure of its manufacturing operations in Brooklyn. The company is apparently now focusing on educational and professional markets rather than consumers. 3D Systems also recently announced it would no longer produce its entry-level Cube 3D printer, would shut down the accompanying Cubify platform, and would be focusing on educational and “engineer’s desktop” markets.

As for 3D printed guns, attempts to remove the Liberator’s design files from file-sharing platforms have largely been successful, although someone who is determined to find them can no doubt do so in the less salubrious parts of the internet. For the average person, though, the still-rudimentary nature of cheap 3D printers, and the time and effort needed to create a printed gun, are major barriers. In most cases, it is probably easier and more efficient to obtain a firearm through conventional means, whether licit or illicit. Interestingly, among the organisations most interested in the 3D printing of weapons are the conventional military of countries including Australia and the United States; so much for 3D printing signalling the death of nation-state control.

Implicitly, 3D printing challenges the design of intellectual property laws and similar protections, and the belief that these laws can be enforced relatively well by regulating the centralised entities that perform gatekeeping roles. In practice, things have been rather different. While we can’t discount the possibility that the future will bring better, cheaper machines and more widespread take-up of 3D printing, we don’t yet seem to be in that post-control, post-scarcity world.

Which is why it will be important to monitor 3D printing’s real-life development. It might also be a good idea for scholars and commentators to take a more measured, and less technologically deterministic, approach to 3D printing and other developments. Another recent innovation accompanied by similar hyperbole is Bitcoin and the blockchain. As with 3D printing, governments and corporations have taken a great interest in these applications for their own purposes. We might want to think more about the mainstream uses of these technologies than about the extreme examples that have tended to grab headlines. •