The abysmal performance of the polls in the 2019 election poses two last questions. We know the pollsters unanimously predicted the wrong result, but for how long had they been wide of the mark? And how did that influence the course of the campaign?

The polls had been remarkably consistent for the two years leading up to the election. In fact, I can’t find a single reputable poll during that period showing the Coalition ahead, or even managing 50 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote. Perhaps late deciders went disproportionately to the Coalition, but there is nothing in the polls to suggest much movement as election day drew closer. Indeed, Newspoll detected a very slight, half-a-per-cent swing to Labor in the last week.

It is possible, even likely, that major-party support at the beginning of the campaign — and perhaps much earlier — was level-pegging, or even that the Coalition was ahead. If that reality had been reflected in the polls at the time, how different would the campaign have been? Faced with the danger of losing rather than what looked like the certainty of winning, would Labor have campaigned differently? And if the media hadn’t shared the all-but-universal assumption that Labor would form government, would they have scrutinised Scott Morrison and the Coalition more closely?

With a win apparently assured, Bill Shorten seemed determined to take the high road to victory. Even as the criticism of Labor’s franked-dividend and negative-gearing policies became more ferocious, Labor made no attempt to finesse or soften them. If the polls had been neck and neck, would Shorten and his colleagues have been more flexible? Labor ran an unusually positive campaign, concentrating on its own policy proposals; if it had thought it might lose, would it have tried harder to keep the focus on the government’s failings?

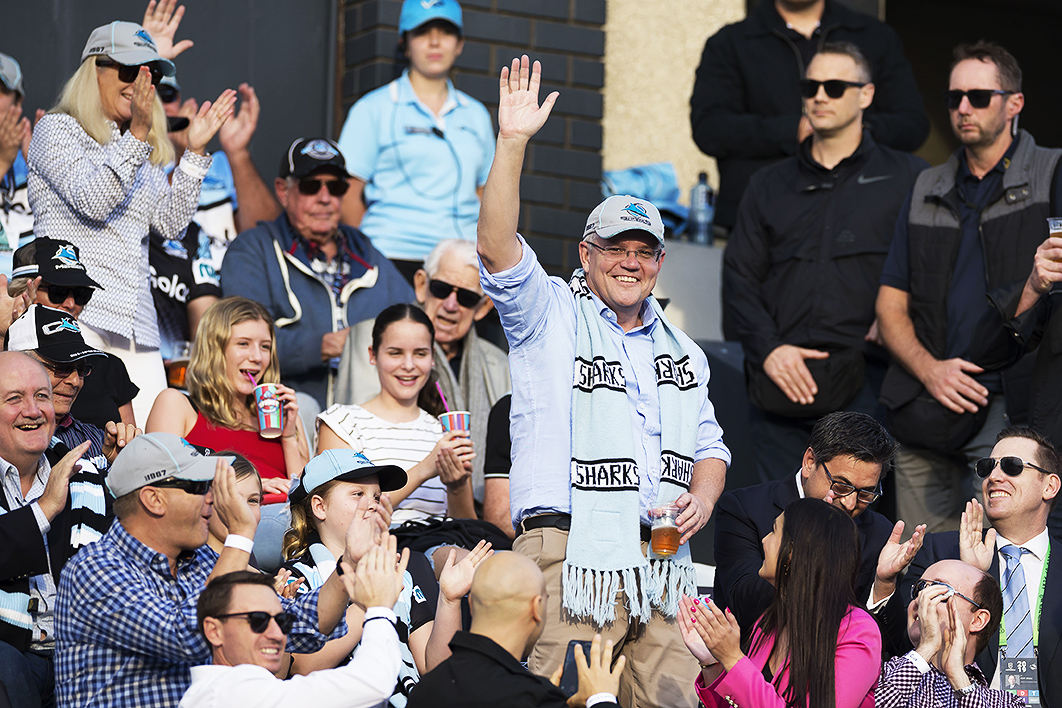

Morrison, by contrast, was able to take the low road to victory. Very few governments running for re-election have been able to direct the focus so strongly onto the opposition. The media generally scrutinise the alternative government more closely as the election gets nearer, but this campaign was notable for how little the government’s record or its plans for the coming term of government figured.

The rather threadbare positive side of the Coalition’s campaign featured three elements. One was its claim to superior economic management, captured in its promise that the budget introduced for the coming financial year would be in surplus. But even this claim to virtue was overshadowed by its dire predictions about what would happen under Labor’s leader, “the Bill Australia cannot afford.”

The second element was the promise of large tax cuts, projected a preposterous ten years into the future to make the benefits seem greater. Without much scrutiny, the Coalition simply asserted that these cuts could be made while keeping the budget in surplus and without harmful cuts to spending. Labor’s costings and tax policies, by contrast, were subject to intense analysis and criticism.

The third element was a sweeping series of local projects, which largely passed under the radar of the national media. In this unashamed example of widescale pork barrelling, it isn’t clear how many projects were of social value or represented value for money.

Post-election, with Morrison’s stunning victory lending a halo of success to all he did, commentators have tended to forget some of the more bizarre aspects of his campaign. After lower-house crossbenchers and Labor defeated the government on the medivac legislation, Morrison sought to dramatise the consequences by re-opening the Christmas Island facility. A few weeks later, after the huge influx of asylum seekers failed to materialise, he closed it again, having spent an enormous amount on an extravagant pre-election gimmick.

Equally absurd was the government’s campaign against electric cars, and its casting of Labor’s aspiration that half of the new cars sold in Australia would be electric by 2030 as an attack on tradies and boat owners.

If the Coalition’s re-election had been seen as likely then its cynical and erratic polices on global warming would surely have been subjected to more scrutiny. Instead, environment minister Melissa Price gave not a single interview during the campaign, a reflection of a belief within the Coalition leadership that she couldn’t be trusted to handle difficult questions on this key portfolio. Morrison removed her straight after the election, despite having denied during the campaign that he would do so. Several times the government made blanket assertions about its progress on global warming, but few journalists showed great interest in probing the claims.

No doubt expecting Labor to take government, the media went along with the Coalition’s strategy of focusing on the opposition. Labor put forward perhaps the most economically responsible and carefully costed election platform in many years. Its reward was the deliberate misrepresentation of its “retiree tax,” its “housing taxes” and even, largely on social media, its completely fictitious “death tax.”

The Coalition’s campaign was in many ways an unsubtle throwback to the 1950s and 60s, when it cast Labor as inherently unfit to govern. When Labor announced a $4 billion plan to improve childcare, education minister Dan Tehan dismissed it as “a fast track to a socialist, if not communist, society.” Morrison told a business meeting that “the union movement will basically be in control of your business if the Labor Party is elected.”

It is miraculous what Morrison got away with. The sense of shock on election night was very much a product of the expectations generated by the polls. But the way the campaign itself unfolded may also have been the product of how those expectations shaped the behaviour of the parties, the media and perhaps even, indirectly, the electorate. •