One of the stranger characteristics of the nineteenth century was that while it prided itself on being progressive, it was also intensely historicist. Consider London’s St Pancras Station: it’s at once a neo-medieval folly, and a temple to state-of-the-art Victorian technology. The new idea of evolution could be said to have underpinned both impulses. Achievement could not be understood, it was felt, without due attention being paid to origins.

The Oxford English Dictionary was partly based on these assumptions. But the idea didn’t come out of nowhere. In Germany, the brothers Grimm (yes, they of the fairy tales) had embarked on a German dictionary that proved the exemplar. Applying comparative linguistics, it was they who pioneered the descriptive method of defining and tracing a word’s meaning across time — and who also, more practically, devised the crowdsourcing techniques and everyday policies and practices adopted by the OED editors.

Arising from a proposal made to the London Philological Society, the dictionary took some time to attach itself to Oxford. But in practice — rather like the University of Melbourne and Meanjin — Oxford was reluctant to fully endorse the project.

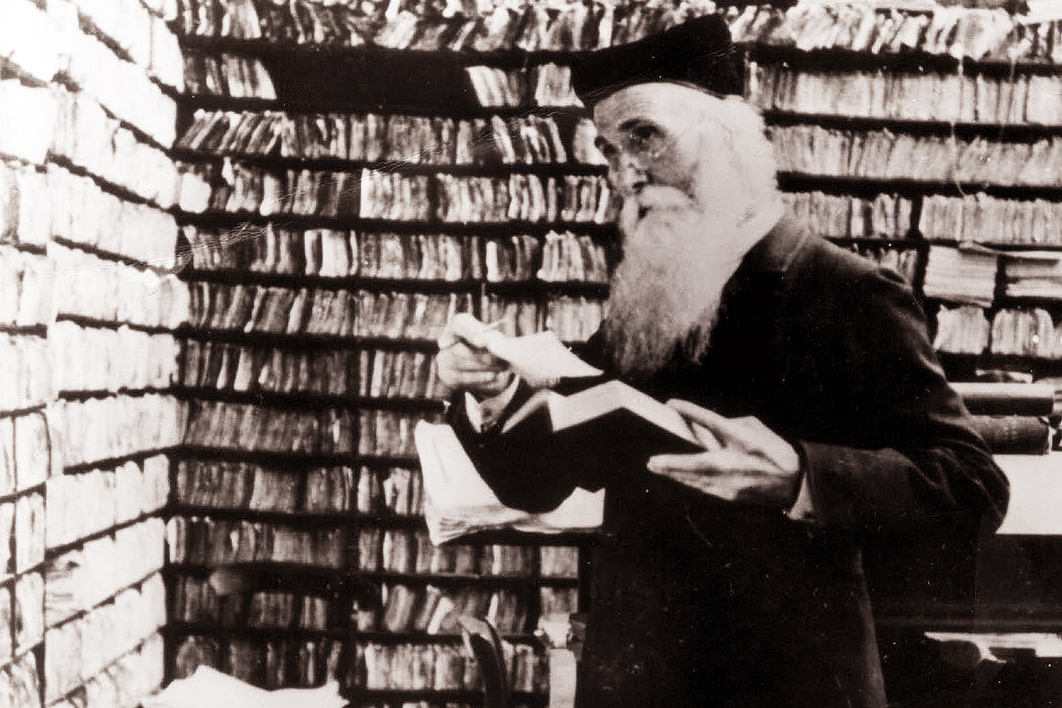

James Murray, whose long editorship from 1879 to 1915 was crucial, was never embraced by the establishment. He was underpaid, given a grant by the university which (unrevised) had to cover expenses as well as provide him with a salary. Indicatively, the dictionary operated not from an office amid the dreaming spires, but from a large tin shed — “the Scriptorium” — built by Murray in his own backyard. It was often so cold that staff working there had to wrap old newspapers around their legs.

In Oxford Murray was an outsider: a Scot who left school at fourteen, an agnostic and a liberal moving among Tory Anglicans — and without benefit of the usual social props, for he was a teetotaller and non-smoker. Beyond concerns with his large family — often recruited to dictionary work — Murray applied himself totally to the great project.

When Sarah Ogilvie happened upon Murray’s (undisturbed) address book, she realised she had found the key to how the dictionary worked. Here all the contributors were listed — the people who read books (usually sent to them) and recorded strange words, with their context, on standard slips that were then sent back to Oxford. (So many arrived that the post office put a special pillar box outside Murray’s house.) Often they read in areas totally disjunctive from their professional concerns; they were complemented by specialists who were consulted as the need arose. Staff then organised the citations according to shades of meaning, Murray generally providing the definitions.

Ogilvie soon found that a lot of the readers were outsiders too. “The OED,” she writes in The Dictionary People, “was a project that attracted those on the edges of academia, those who aspired to be part of an intellectual world from which they felt excluded.” And some had been, in the most absolute sense. One was Dr Minor (whose story has been told by Simon Winchester in The Surgeon of Crowthorne), locked away as a murderer in an institution for the criminally insane. Others too had mental problems; obsessionals were attracted to such projects.

But many were also progressives; a number of the women were suffragists — less militant than the suffragettes — while the men were sometimes rationalists or vegetarians. One contributor, the acclaimed writer of verse dramas Michael Field, was in fact a lesbian couple, doubling their everyday roles as aunt and niece. But conventional families were also involved: reading for the dictionary around the fireside could be a wholesome collective enterprise.

As one might expect, there was a contingent of vicars. But the army of readers included a great variety of people, many of whose stories are briefly told. Perhaps the most extraordinary was Sir John Richardson, a survivor of Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated polar expedition, who had been reduced to cannibalism and also killed a man. Then there was Eleanor Marx, Karl’s daughter, unsatisfactory from the dictionary’s point of view but a notable translator and political activist. Contributions also came from Henry Spencer Ashbee, who had built up the world’s largest collection of pornography, an embarrassment to the British Museum when he left it to them. And so the list could go on — although it includes few novelists.

But it did extend across the world — to places as different as Jamaica, China and Madagascar. Particularly significant was a node in Melbourne, where E.E. Morris, building on a network of well-placed English immigrants, gathered so many words that he was prompted to write a special Dictionary of Austral English.

Yet the OED, while both an exercise in soft power and a kind of cultural stocktaking, was not overtly imperial. This can be seen in its attitude to America, where it enjoyed huge support — the New York Times publicised the venture and American academics were always helpful. (English ones were rather frosty.) For his part Murray maintained that Americanisms “must be admitted on the same terms as our own words.” This involved recurrent tussles with the Delegates of OUP. He was right: later H.L. Mencken pointed out that in the eighteenth century, the fastidious had bridled at the transatlantic crossing of such words as “talented,” “reliable” and “lengthy.”

Murray was interested in local, indigenous words that were in common use among English-speakers. British imperialism and interaction across the world was so extensive, and English’s origins so mixed, that the language is said to contain almost three times as many words as French. This partly explains the size of the dictionary, with its ten walloping volumes, and the fact that it wasn’t completed till 1928.

A number of books have been published about the dictionary. There’s Peter Gilliver’s The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary and the acclaimed biography of Murray written by his granddaughter, Caught in the Web of Words. But the unique attribute of this one is that it is focused on the foot soldiers of the enterprise, and the contribution they made.

In the last few pages of the book, Ogilvie reveals that she is from Brisbane, and had been fascinated by the slips that arrived in Oxford from a Mr Collier, bundled together in old cereal packets. He too was from Brisbane, and so on a return visit she sought him out. A bachelor and a shorts-and-T-shirt man, he was capable of casting off his clothes and running nude through suburban streets in the dead of night.

Since Collier had been so assiduous — sending 100,000 slips — she raised the possibility of his being flown to Oxford. “No way,” he said; “imagine all the Courier-Mails waiting for me on my return.” Indeed, as she points out, the citations from the Courier-Mail exceed those from Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot or the Book of Common Prayer.

In his own distinct way, Collier fitted what Ogilvie would come to see as the classic contributor template: an autodidact, an isolate with strange ways, but hell-bent on getting a word into the dictionary. She took steps to have him awarded a gong for services to the Australian language, but unfortunately he died too soon. Ogilvie’s interest in contributors broadened then, and this book is the happy result. •

The Dictionary People: The Unsung Heroes Who Created the Oxford English Dictionary

By Sarah Ogilvie | Penguin Random House | $35 | 368 pages