It’s a puzzle. The Turnbull government almost brought off a really good budget. But it has chosen to focus our attention on tax cuts that won’t happen, if they do happen, for six years, and are aimed at the top 10 to 15 per cent of taxpayers.

The centrepiece of the budget could have been the return to surplus, coupled with the modest but well-targeted tax cuts for lower- and middle-income earners planned for next year. Australians would have welcomed both parts of it. It would have given credence to the Coalition’s claim to be the better economic manager, and chimed with its long-running narrative of trying to get the budget back in the black.

But Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison clearly felt they needed something there for the Coalition’s base, the well-off and those who aspire to join them. So they added a stage two of the tax cuts from 2022–23, which would mean anyone earning between $41,000 and $120,000 would be on the standard marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent.

Okay, there’s a case for that too, so long as the budget can afford it, which is impossible to tell from this point. But by and large, the second round of cuts provides significant savings only to people earning more than $100,000. It offers nothing to the great bulk of taxpayers.

Even that, however, was not enough for Turnbull and Morrison. So they added a third stage of tax cuts from 2024–25, solely for those who are already well-off. The standard marginal rate would apply to incomes all the way up to $200,000.

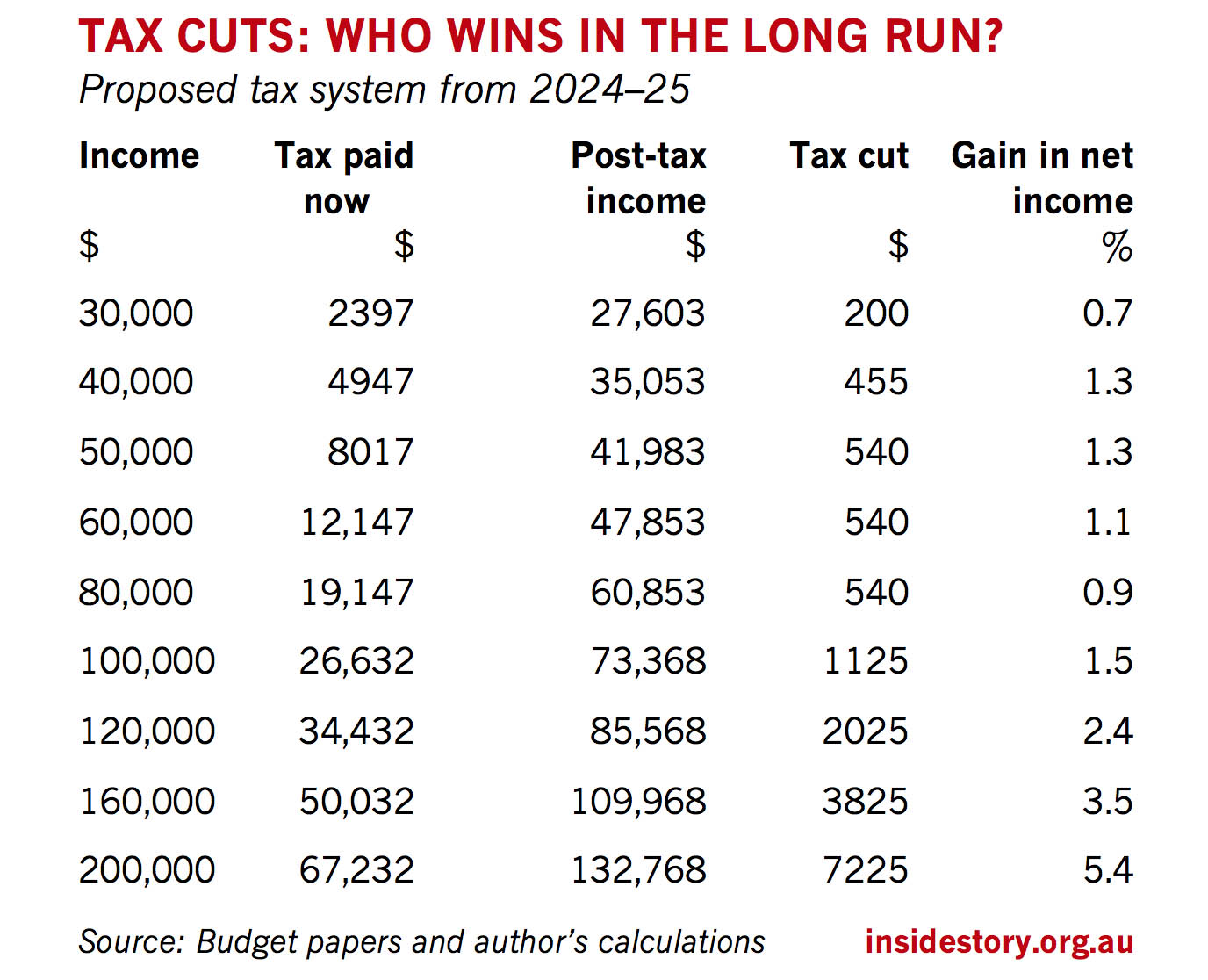

Put it all together, and the panel shows what that means.

A cleaner on $30,000 a year would get a tax cut of $200. A nurse on $80,000 would get a tax cut of $540. But a lawyer on $200,000 a year would get a tax cut of $7225 — thirty-six times as much as those on low incomes.

The best measure is the gain in incomes after tax. Everyone earning up to $100,000 a year, the vast bulk of Australians, would get an increase in disposable income of around 1 per cent — and that’s their only tax cut for fifteen years. Those on $200,000 a year would get a boost in disposable income of 5.4 per cent.

That’s fine if you think that what’s wrong with Australia is that the rich have too little money and the poor have too much. I doubt that many swinging voters share those values. It’s a very easy target for Labor to attack, and the fact that it would not happen for six years — two elections away — makes it implausible as well.

Why give your opponents a second target when you are already on the defensive over unpopular company tax cuts and you have a good story to tell in the shorter-term budget projections? Future historians will wonder.

If you accept the budget’s assumptions, the next four years look very good for the economy, and the budget itself. It projects growth of 3 per cent a year throughout that period, which seems to me a reasonable forecast for the next two years, at least.

It projects employment to grow by 700,000 jobs, although with only a slight reduction in unemployment, presumably because most of the jobs, as over the last decade, will be taken by recent migrants.

The budget surplus would be achieved a year early, in 2019–20, albeit at a skinny $2.2 billion, just 0.1 per cent of GDP. But then it would climb to $11 billion in 2020–21 and $16.6 billion a year later, before settling down at about 0.5 per cent of GDP as a result of all those tax cuts. It takes until 2026 to reach the target the government set for itself of 1 per cent of GDP, but for the next four years the trajectory would be admirable if achieved.

(I suspect many readers think that surpluses don’t matter. They do. Remember that over the past decade, Australia has run budget deficits averaging 2.5 per cent of GDP. That’s why we have a net debt estimated to hit $350 billion next year, plus another $23 billion of debt held by off-budget companies such as NBN, Inland Rail, Western Sydney Airport etc. That money has to be paid back in good times, otherwise the interest bills will weigh on future budgets indefinitely, as they do in Europe, eating up money that should be used to provide government services or lower taxes.)

But it is very doubtful that that trajectory will be achieved. The forecast budget surpluses in 2019–20 and beyond depend on another set of numbers that look decidedly flaky.

Wage growth has averaged 2.1 per cent over the last three financial years and, despite many official forecasts of rising wages, was still stuck there when last measured at the end of 2017. Yet Treasury, undeterred, has forecast that it will surge to 2.75 per cent in the next financial year, then to 3.25 per cent in 2019–20, and then to 3.5 per cent.

What is Treasury’s forecasting record? In the past two budgets, on average, it overstated wage growth for the year ahead by 0.5 per cent, and for the following year by 0.7 per cent. If it’s that far out again this time, the thin surplus forecast for 2019–20 will disappear, and those in future years will be much reduced.

The other dubious assumption in the budget is that spending growth from 2019–20 will be contained to average just 1.1 per cent a year in real terms over the next three years — which implies real falls in per-capita spending, since the population is growing by 1.6 per cent, and the government wants it to stay that way.

That is only half the 2.1 per cent average growth in real spending over the government’s two terms in office — in which the austerity has been pretty severe in many places, including the lack of wage rises for many public servants.

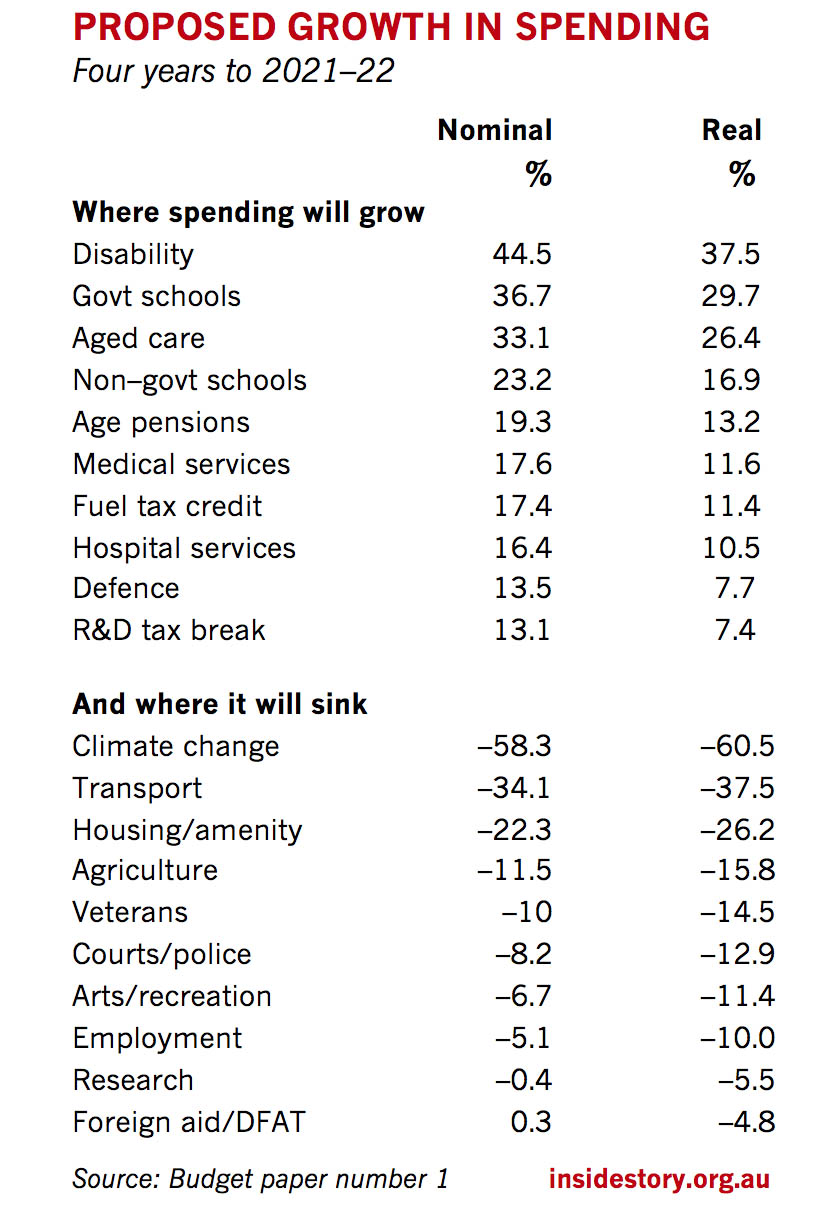

If you look at the projected spending in different policy areas, you see only islands of real per-capita growth, mostly the areas the government has specifically prioritised (schools, the NDIS), or where the ageing population is forcing it to spend more.

Some of those contradict the image of the Coalition held by many on the left. By and large, the Coalition has delivered the hard part of the bipartisan commitment to a properly funded NDIS. It is seriously tackling the relative disadvantage of government schools, while Labor has opportunistically played up the complaints of overfunded Catholic schools. The Coalition might not be spending as much on hospitals and medical services as we would like — the 50/50 split of hospital funding between Commonwealth and states was a good rule we should bring back — but it is increasing funding for them substantially.

But if nominal GDP rises 18.7 per cent in the same four years, as Treasury forecasts, then only spending on the NDIS and schools will be growing as a share of GDP. (I don’t count aged care, because that spending boost is just a correction to the misguided cuts in an earlier Coalition budget.) Spending on everything else, even defence, will be shrinking as a share of GDP, and in most areas of government responsibility, shrinking in real per-capita terms. This budget means smaller government, with a vengeance.

The budget shows the impact in some of the larger spending areas. Renewable energy subsidies, of course, are slated to end (and given the speed with which renewables’ prices are falling, that’s one of the more defensible cuts). It is heartless that the government has slashed real support for social housing at a time when so many are homeless and living on the streets. The ABC has been singled out again for cuts, with a three-year funding freeze. Funding for employment programs for jobless Australians, as well as vocational education, has taken severe cuts.

And, to its shame, this government proposes to reduce foreign aid to the lowest levels, as a share of our income, since records began. China, of course, has been doing the opposite. We are making ourselves less relevant to our neighbourhood. They are making themselves more so.

Then there is transport. Turnbull talks up his $75 billion program for transport infrastructure as if it is all happening here and now. But it is a ten-year program, and much of it has been moved off budget. It will be a long time before you can take a rail trip to Melbourne airport.

Transport spending within the budget is shrinking, and not just in the outyears, where projects are yet to be decided. For 2018–19, total transport investment in the budget will be cut by 9 per cent, in both rail and road. Investment in key projects will be slashed by 13 per cent from the equivalent plans a year ago.

But isn’t that coming off historic highs? In nominal dollars, yes — in nominal dollars, most things are usually at a historic high. But as a share of GDP, both total infrastructure investment and transport investment specifically were significantly higher under the Rudd–Gillard government than they are now.

In calendar 2011, the Bureau of Statistics reports, new transport construction by or for governments made up 1.21 per cent of Australia’s GDP. In 2017, it was just 1.10 per cent. And, of course, in 2018 and 2019, it will be even lower. We talk about it more now, and there is more of it because there are more of us. But for all that, it has slid down the scale of our spending priorities at a time when the surging population in our four largest cities has made the need for it greater than ever.

The Bureau’s figures include both budget spending and spending on projects that have been moved off the budget, on the grounds that they are — supposedly — commercially viable. Labor pioneered that trick to keep the NBN off budget, and the Coalition has adopted it with gusto.

It has now put its spending on Western Sydney Airport and Inland Rail off budget, claiming that they are commercially viable, even though Inland Rail executives concede that it won’t make profits in the next fifty years. Snowy 2.0 will be off-budget if it happens, as will the Melbourne Airport Rail Link, if the Victorian government seizes Turnbull’s offer to unload half its ownership (and future losses) onto Commonwealth taxpayers.

If all this was happening on budget, the budget balance would look very different. In 2018–19 alone, the government’s non-financial corporations are forecast to add another $10 billion of net debt, while the budget sector itself adds just $9 billion. It’s one of those tricky details that remind us that once a government sets a rule for itself, it quickly starts finding ways around it.

To sum up: the government is forecasting an admirable path back to surplus, but it depends on heroic assumptions about wage growth, and on its plans to cut real government spending per head in most areas. Its three-stage tax plan begins well, but ends with handing out big bickies to those who have, and little ones to those who have not. And while the atmospherics suggest record infrastructure spending, the Bureau of Statistics figures show that is a mirage.

But tax is where the debate will focus. The government now plans to bring in legislation to limit taxes to 23.9 per cent of GDP, and make the coming election something of a referendum on tax. The faultlines will be predictable, but the evidence of the polls suggests that voters in the middle tend to prefer better services to lower taxes.

Certainly the economic case for the plan is weak. High-tax countries like Sweden have been just as successful as low-tax countries like Switzerland; it’s how you raise the taxes and what you do with them that matters. The Howard government itself went over the proposed limit in every year from 2000–01 to 2005–06 — except for 2001–02, when it instead went into deficit.

As Brendan Coates and Danielle Woods argue, the growing costs of an ageing population make it inevitable that taxes too must grow, or other services must be cut to make room for them.

One of those services is defence. If one shares the Coalition’s unease about the way China intends to use its new power in the region — not just under its current leader, but under future leaders brought up on its claims to hegemony over the rest of us — then there is surely a strong case for increasing defence spending from 2 per cent back to the 2.5 per cent it averaged over the decades of the cold war.

I don’t suggest that lightly. The future role of a dominant China is the most serious issue that Australia has faced in my lifetime. Few of us will be experts on it, but more of us should be thinking about it. If we see China as a potential threat, then defence has to claim a much bigger share of our future spending. There is no hint in the budget that the government is prepared to do that.

It is disappointing that the Turnbull government has adopted the tax limit as policy without considering other needs that conflict with it. It is a glib gimmick. Australia has the eighth-lowest taxes of the thirty-four nations in the OECD. In 2015, the only countries where taxes were lower were Chile, Ireland, Korea, Mexico, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. Twenty-six countries had higher taxes, most of them much higher, including successful economies such as Austria, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Britain.

The government appears to want tax versus spending to be the election issue. It has chosen to fight on weak ground in economic and, I suspect, political terms. It will make for a historic ideological battle.●