We are used to the Coalition being unable to get its legislation through the Senate. But what if an incoming Shorten government is unable to get its legislation implemented too?

That’s very likely to happen. My examination of potential Senate outcomes suggests that even if Labor wins the next federal election, the left (Labor and the Greens) will be even weaker in the next Senate, with as few as thirty-four of the seventy-six seats.

The first of these two thoughts is not an original one: it comes from an important column by Phillip Coorey in Friday’s Financial Review.

Coorey pointed out that Labor can only provide the income tax cuts and new spending it is spruiking if it can get its tax changes through the new Senate. Its proposals to end negative gearing and lift capital gains tax might get the new Senate’s tick of approval, but two other key pieces of its legislation are supported only by the Greens.

They are:

- Its plan to take back the company tax cuts that are already law for companies with income of up to $50 million a year. Labor has floated the idea of reducing the threshold to $10 million, but that is very unlikely to win support from the senators who voted the $50 million limit into law.

- Its plan to lift the top marginal income tax rate from 47 per cent to 49 per cent, generating a tenth of the new revenue Labor is counting on. This also has no support from the crossbench, apart from the Greens.

“Consequently,” Coorey concludes, “unless Labor and the Greens boost their Senate numbers to a combined thirty-nine votes at the election, Labor’s $220 billion war chest could be reduced by between $50 billion and $100 billion.”

That’s serious. Our budgets over the past five years became untrustworthy partly because the government kept including “zombie” savings measures that had never passed the Senate. Will its zombie savings be replaced by Labor’s zombie tax hikes?

This is no minor issue or cheap political point: it goes to the heart of Labor’s program, and its ability to deliver what it is promising. Of course, the election could be up to a year away, and this is not Labor’s ultimate election platform. But we’re getting close.

The idea that Labor could persuade the Senate to raise company tax by repealing the tax cuts already passed after so much debate fails any pub test. A Labor campaign policy that includes that will not be believable.

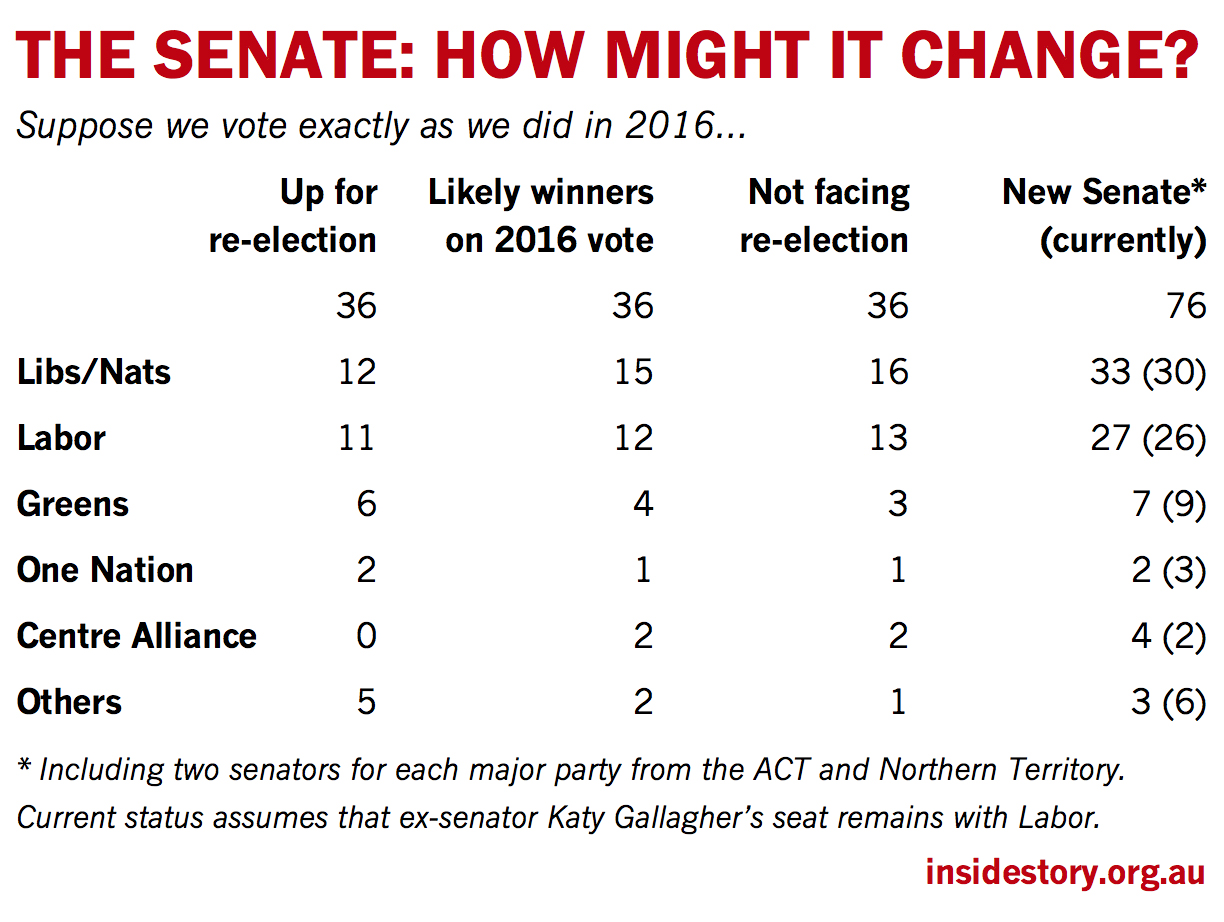

In fact, the new Senate is likely to be even less supportive of Labor. We know that because after a double dissolution, as we had in 2016, senators are divided into two groups. The first six to be elected in each state get six-year terms, and the other six get three-year terms. It is the latter group that will face us at the next election.

Of the thirty-six senators whose term extends to 2022, only thirteen are Labor, and three are Greens, whereas eighteen are on the right: sixteen from the Coalition, Pauline Hanson, and Liberal defector Cory Bernardi, now leader of the Australian Conservatives. In the middle are Stirling Griff and Rex Patrick, the two remaining senators of the Centre Alliance (formerly the Nick Xenophon Team). The left goes into the election already two seats behind, 16–2–18.

Of the thirty-six senators from the states whose terms expire next year, seventeen are on the left — eleven Labor and six Greens — three are arguably in the middle (Derryn Hinch, Xenophon defector Tim Storer, and Lambie defector Steve Martin), and just sixteen are on the right: twelve from the Coalition, One Nation senators Brian Burston and Peter Georgiou, One Nation defector Fraser Anning and Liberal Democrats leader David Leyonhjelm. On that classification, it’s 17–3–16 — or if you classify Hinch and Martin as leaning to the right and Storer as leaning to left, it’s eighteen-all.

No one can predict the outcome of the Senate election from this distance. Malcolm Turnbull doesn’t have to hold it until mid May 2019. We don’t know how popular the parties will be when we vote, or which candidates will be standing.

But we can construct a baseline. What would have been the result had the 2016 election been run as a half-Senate election — as the next one is likely to be — rather than the full-Senate election it was?

At a half-Senate election the quota needed to win a seat is 14.3 per cent; at a full-Senate election it is lowered to 7.7 per cent, which is why so many crossbenchers were elected.

I have tried to estimate the outcomes of the 2016 voting with the higher quota. Some of them are a matter of judgement; because of the way Senate votes are counted, even major parties are often eliminated early in the count, and you can’t tell precisely how many preferences they would have won. (The four seats from the territories are contested at every election, and always split two/two between the major parties, so they are not analysed.)

On my estimate, had 2016 been a half-Senate election, the Coalition would have won fifteen seats to Labor’s twelve. The Greens would have come down from six seats to four, and five crossbenchers would have won seats: Nick Xenophon and his running mate; Pauline Hanson; Derryn Hinch; and Jacqui Lambie.

Note: that is the baseline we start from, not a forecast of where we will finish. But on that baseline, Labor would be one seat better off and the Greens two seats worse off. The combined left would be one seat down. The Coalition would be three seats better off, the Xenophon team two better off, and the other crossbenchers would be four seats down. One Nation’s Brian Burston and Peter Georgiou, One Nation defector Fraser Anning, and Xenophon defector Tim Storer would not be sitting in the Senate.

The baseline would see Labor with twenty-seven seats in the seventy-six-member chamber, and the Greens seven. The Coalition would have thirty-three seats, One Nation two, the Xenophon team four, and the others would be Bernardi, Hinch and Lambie. That’s a tough Senate for a party with a policy of raising taxes.

As I explain below, current polling and recent elections point to slightly different outcomes in some states, but they would not significantly alter that balance. Labor will have to design its policies for, and be ready to live with, a Senate that is generally against raising taxes.

There are two rules of thumb for Senate voting. The first I call the Mackerras rule, because I think the political scientist Malcolm Mackerras was the first to point it out. If there are six senators to be elected in a state, they will normally split three-all between left and right.

In the first five Senate elections under this system, the Mackerras rule worked well: between 1990 and 2001, in what were effectively thirty state elections, all but two split three-all between the left (Labor, Australian Democrats, Greens) and right (Liberals, Nationals, and former Tasmanian independent Brian Harradine). The exceptions were in New South Wales in 1990, when the Reverend Fred Nile preferenced Labor to ensure the defeat of progressive Liberal senator Chris Puplick, and in the same state in 1998, when Labor was riding high with its pledge to dump the GST.

But then along came Glenn Druery, with his dark art of “preference whispering,” to persuade other minor parties to direct their preferences to the party or parties paying him. At the same time a growing alienation from conventional politics saw the rise of a range of minor parties or individual candidates: Pauline Hanson and One Nation, Nick Xenophon and his team, Clive Palmer and his Palmer United Party, Jacqui Lambie, Derryn Hinch, and so on.

Bizarre things happened. In 2013 David Leyonhjelm of the Liberal Democrats was elected because people saw him at the top of the ballot paper and thought he belonged to the Liberals — yet, as the maths worked out, the seat he won was taken from Labor.

The result of all these things was that the Mackerras rule no longer worked.

But last year’s much-needed reforms to Senate voting by finance minister Mathias Cormann have changed that. The alienation of voters from old-style politicians is still there, but there will be no more politicians elected by bizarre preference deals. The voters now control their own preferences, and at the 2016 election they used them to reinstate the Mackerras rule.

If you classify Hinch and Lambie as centre-right, which seems to me fair, then had it been a half-Senate election, it would have yielded a left–right split of three-all in every state except Queensland. If you’re trying to work out what will happen in each state, that is the most likely outcome. It won’t always happen — in fact, as I argue below, the next battle for the final seat in Queensland and South Australia looks likely to be between Liberals and Greens — but it will be the usual outcome.

The second rule of thumb is that, with voters now controlling their own preferences, the senators elected will almost always be those with the highest first-preference vote.

I have written before about what happens when voters have control over their own preferences: they go everywhere. Journalists still assume that parties’ how-to-vote cards decide elections, but the evidence is overwhelming: most voters in fact ignore them and make up their own minds — and their preferences don’t go where you would expect.

In the 2016 Senate election in Victoria, for example, when the lead Marriage Equality Party candidate was eliminated, you would expect his preferences to flow to parties supporting marriage equality: the Greens, the Sex Party, Derryn Hinch. About half of them did. But the other half went to all sorts of parties, some of which firmly opposed marriage equality. More Marriage Equality voters gave preferences to Family First and to One Nation than to Hinch.

Similarly, later in the count when the Liberal Democrats were excluded, only a third of their voters gave their preferences to the Liberals. The next-biggest swag, 14 per cent, went to the Greens, the party with the least in common with the Liberal Democrats. Voters’ preferences are far more random than you would think.

In 2016, only one result was decided by preferences. That was in Queensland, where the tide of support for Pauline Hanson swept along her number two, Malcolm Roberts, to overtake the Liberal Democrats and claim the final seat. In every other state, the twelve highest-placed candidates on first preferences won the seats. Hence my rule of thumb: the Senate candidates with the highest first-preference votes (which include party-ticket votes) will almost always win the seat.

Let’s look at each state.

New South Wales

In 2016, One Nation’s Brian Burston and the Liberal Democrats’ David Leyonhjelm scraped into the last two seats with 4.1 and 3.1 per cent of the vote respectively. While those votes grew with preferences, they would need to poll much better in 2019 to have a realistic chance of holding their seats. Even the Greens’ Lee Rhiannon polled only 7.3 per cent, just missing the cut for a quota. All three seats are being contested this time, along with two Coalition seats and just one of Labor’s.

On 2016 voting, Labor and the Coalition would win two seats each. The Greens and the Coalition would then have just over half a quota each, with another quota spread among the rest of the field, mostly One Nation (.29 of a quota), Leyonhjelm (.22), and Labor and the Christian Democrats (each .19).

On those figures, the Coalition and the Greens would probably win the two final seats. I’m assuming that the dumping of Lee Rhiannon as Greens candidate for Mehreen Faruqi won’t hurt their vote. One Nation did well on preferences, but would need a much bigger primary vote to be in the contest. Newspoll is showing a hefty swing from the Coalition in New South Wales, and mostly to One Nation, so that can’t be ruled out.

Bottom line: on the 2016 vote, the Coalition would take Leyonhjelm’s seat, Labor would take One Nation’s, and the Greens would hold on. But if current polling is reflected in the vote, the last seat could be a very close battle between the Coalition and One Nation.

Victoria

The 2016 fight became surprisingly close, as the voters delivered a big swag of preferences to Family First (it wasn’t a bad brand name, Cory! Better than Australian Conservatives). Derryn Hinch (6.05 per cent) also won enough preferences to sweep him across the line, followed by Janet Rice of the Greens, with the Coalition’s Jane Hume holding out Family First’s Ashley Fenn for the last seat.

For a half-Senate election, the Coalition polled 2.32 quotas, Labor 2.15, the Greens 0.76 and Hinch 0.42. No other party polled well enough to have a chance. The preference distributions would have given the Greens one seat, with Hinch probably taking the other. When he was declared elected and removed from the count, he had .58 of a half-Senate quota and Hume .48. Preferences from Family First, the Sex Party (now renamed the Reason Party) and One Nation would have decided the outcome, and Hinch probably would have held his own there.

But Senator Hinch will be seventy-five next year, and eighty-one in 2025, when the next six-year term will end. He gave us a shock when he stood in 2016, but it will be another shock if he volunteers for a second term. Again, Newspoll shows the Coalition has lost support in Victoria — to Labor as well as One Nation.

Bottom line: on 2016 voting, there would be no change in Victoria’s representation; Hinch would hold on. In real life, he would probably win if he stood again. If he doesn’t, his seat will go to the conservative side; with One Nation weak in Victoria, that probably means the Coalition.

Queensland

In 2016 One Nation’s Malcolm Roberts won the final seat from Family First on a tidal wave of preferences intended for Pauline Hanson, but then the High Court ruled that he was still a Brit. The next in line on One Nation’s ticket was Fraser Anning; his leader told him to give up the seat, but Anning decided instead to give up One Nation, and now sits as an independent.

So the six facing the voters next year will be two Coalition, two Labor, a Green (Larissa Waters, who outed herself under section 44, but is coming back for a second bite), and Senator Anning. On 2016 voting, the Coalition would have won two seats clearly, Labor two and Hanson one, with preferences probably giving the Coalition the final seat narrowly ahead of the Greens.

If that vote were repeated, One Nation would regain its lost seat from Anning, and the Coalition would take the Greens’ seat. But the Coalition has lost ground to both Labor and One Nation since 2016.

Bottom line: on 2016 voting, the Coalition would gain a seat from the Greens. But in 2019, that will be a very close contest, and is more likely to go the other way, restoring the three–three balance.

Western Australia

The WA election in 2016 unexpectedly saw Pauline Hanson steal a seat from the Coalition, and strong preference flows gave the Greens and One Nation’s Rod Culleton the final two seats ahead of the Nationals. The most colourful of all the new senators, Culleton was lost to us early owing to his run-ins with the law when he tried to stop the banks repossessing farms. His brother-in-law Peter Georgiou took his place.

On 2016 voting, a half-Senate election would have been straightforward. The two Coalition parties between them won 2.87 quotas, Labor 1.98 and the Greens 0.74. One Nation was a long way back with just .28 of a quota.

But Newspoll reports that the Coalition’s support in Western Australia has fallen from 49 per cent at the 2016 election to just 39 per cent in the March quarter, with most of that going to Labor. One Nation was polling a humble 7 per cent, the Greens 9 per cent, and others 6 per cent. On those figures, the only thing certain is that Labor and the Coalition will win at least two seats each.

On the Mackerras rule, one seat will be fought out between Labor and the Greens, and the other between the Coalition and One Nation. Western Australia has produced four–two results in 2007 for the left and 2014 for the right, but it’s hard to see that happening this time.

South Australia

The 2016 election in South Australia went right to the line, with three seats determined in the final three counts: one to Sarah Hanson-Young of the Greens, one to Skye Kakoschke-Moore of a party then called the Nick Xenophon Team, and one to Bob Day, then the leader of a party that at the time was called Family First. Labor’s Anne McEwen was the loser, edged out by just 3500 votes or 0.17 per cent.

Hanson-Young is still there as a Green. Kakoschke-Moore has gone, and her party is now called the Centre Alliance; her replacement, Tim Storer, was elected for the Xenophon team but now sits as an independent. Nick Xenophon himself has gone, and in his place is Rex Patrick. Bob Day too is gone, and so is his party, which is now called the Australian Conservatives, and is led by Cory Bernardi, who in 2016 was elected as a Liberal. Day was replaced in the Senate by Lucy Gichuhi, who is now a Liberal but was elected for Family First.

Does anyone find this Senate confusing? You are not alone.

That election was the high point of Nick Xenophon’s rise, which made his team a third major party in South Australia. At a half-Senate election, the 2016 voting would have given the Xenophones two seats, the same as Labor and the Coalition. If South Australians vote that way next time, Hanson-Young, Storer and Gichuhi would all lose their seats, with Labor gaining one and the Centre Alliance two.

But the evidence suggests South Australians won’t vote that way. Newspoll reports that the Coalition has maintained its vote, but the Xenophon team has lost ground, mainly to Labor. The recent state election bore this out. The vote for the Legislative Council, elected on the same basis as the Senate, suggests the Xenophon team will more likely get just one senator of the six — possibly Xenophon himself.

If the Council vote applied at a half-Senate election, the Liberals would win 2.26 quotas, Labor 2.03, Xenophon 1.36, the Greens .41 and the Australian Conservatives .24 of a quota. The Liberals would get a big slice of the Conservatives’ preferences, but most of the smaller parties’ preferences would end up with the Greens. As in Queensland. the final seat will probably be Greens versus Liberals — and the outcome could depend on how the new Liberal state government is faring with voters.

Bottom line: on 2016 voting, it’s 2–2–2. But unless Nick can make the moussaka rise again, it’s more likely to end up as 3–2–1 for the Liberals, or 2–2–1–1, with Hanson-Young (who last week won a close preselection battle with former senator Robert Simms) winning another term.

Tasmania

Tassie in 2016 saw one of the closest Senate contests ever. The Greens’ Nick McKim held off One Nation’s Kate McCulloch by just 103 votes, or 0.02 per cent, after Hanson’s party again won the biggest swag of preferences. Many Tasmanian voters ignored the party ticket to vote for Lisa Singh (Labor) and Richard Colbeck (Liberal), who had been dumped to sixth and fifth spots on their party tickets by conservative colleagues. Singh made it, Colbeck just missed out.

But the High Court’s rulings brought Colbeck back, in place of former Senate president Stephen Parry (disqualified under section 44). Devonport mayor Steve Martin replaced the one and only Jacqui Lambie. Like Fraser Anning and Tim Storer, his leader promptly told him to give up his seat, but instead he gave up his party and sits as an independent. Soon Colbeck, Martin, McKim, Singh and two other Labor colleagues will all be facing the voters.

In a half-Senate election on 2016 voting, Labor (2.35 quotas) would lose a seat and the Liberals (2.28) gain one. The Greens (.78) would hold their seat, and Lambie (.58) would be odds-on to take the last seat, assuming she stands. In effect, Martin would return his seat to Lambie, and Labor would give up a seat to the Liberals.

(Why does Labor have three senators in the B-team and the Liberals only one? Why do the Liberals have three senators in the A-team and Labor only two, when Labor had the higher vote?

It’s complicated. Originally the six senators with six-year terms were two Libs, two Labor, one Green and Lambie. But when Lambie had to give up her seat as part of the section 44 purge of parliament, only about half her personal vote went to Martin, and he won the seat only on preferences.

So he slid out of the six-year group, and the Liberals slipped in. Although Labor had a higher vote, the Singh rebellion had pulled a lot of it to the bottom of the ticket, whereas more Liberals had followed the party ticket, so their top three candidates outpolled their Labor counterparts.

It’s ironic. Had Labor’s state heavies not dropped a popular senator to the last spot on the ticket, there would have been no Singh rebellion, Labor would have had an extra six-year term, and an extra senator for the next three years.

Bill Shorten was one of the key figures who blocked reforms to make Labor more democratic by opening Senate preselections to a vote by party members. They call it karma.)

What comes next? Newspoll doesn’t cover Tasmania, and for many reasons the Tasmanian election is little help as a guide. I suspect that if Lambie stands, she will win back her seat, McKim will be re-elected, and Labor and the Liberals will get two each — the same result as in 2016.

Bottom line: Both on 2016 voting and in today’s world, Labor will surrender a seat to the Liberals, and Jacqui Lambie will finally turf her one-time friend Steve Martin (whose maiden speech suggests he’s no lightweight) out of her seat.

The national bottom line is that Labor at best stands to make only small gains to its Senate representation: one seat in New South Wales, and an outside chance of a second in Western Australia. In terms of passing tax legislation, this would probably be offset by losses by the Greens — the Greens could retain all six seats, but most of them are at risk, and it would be surprising if they held them all. At best, the left stands to gain one seat. At worst, it could lose another two.

Of course things could change between now and the election. Something might create a Labor landslide. New candidates could emerge to overturn these projections. Senators could change their minds. But for Labor right now, all that is blue-sky stuff.

The reality right now is that, if it wins, it is almost certain to govern with a Senate that will refuse to scrap its own company tax cuts — and Labor will face a difficult time persuading it to support any unpopular tax hikes. Labor needs to come up with a tax agenda that is politically feasible as well as socially and economically desirable. An agenda that is not politically feasible will not be believable. ●