Mike Smith (1955–2022), a great Australian archaeologist, died in Canberra on Sunday 16 October. As his family announced, “he put down his tools and hung up his hat.” A week before his death he was walking his beloved dog, writing a scientific paper, riding his recliner-bike around Lake Burley Griffin, converting cabbage from his garden into kimchi and no doubt cooking his famed custard tarts. He was a warm, witty, courteous and deeply learned scholar and scientist whose research and fieldwork changed the way Australians understand the recent and deep past of their continent. His book, The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts, published in 2013, is a powerful and enduring encapsulation of his life’s work; my review, first published in 2013, appears below.

— Tom Griffiths

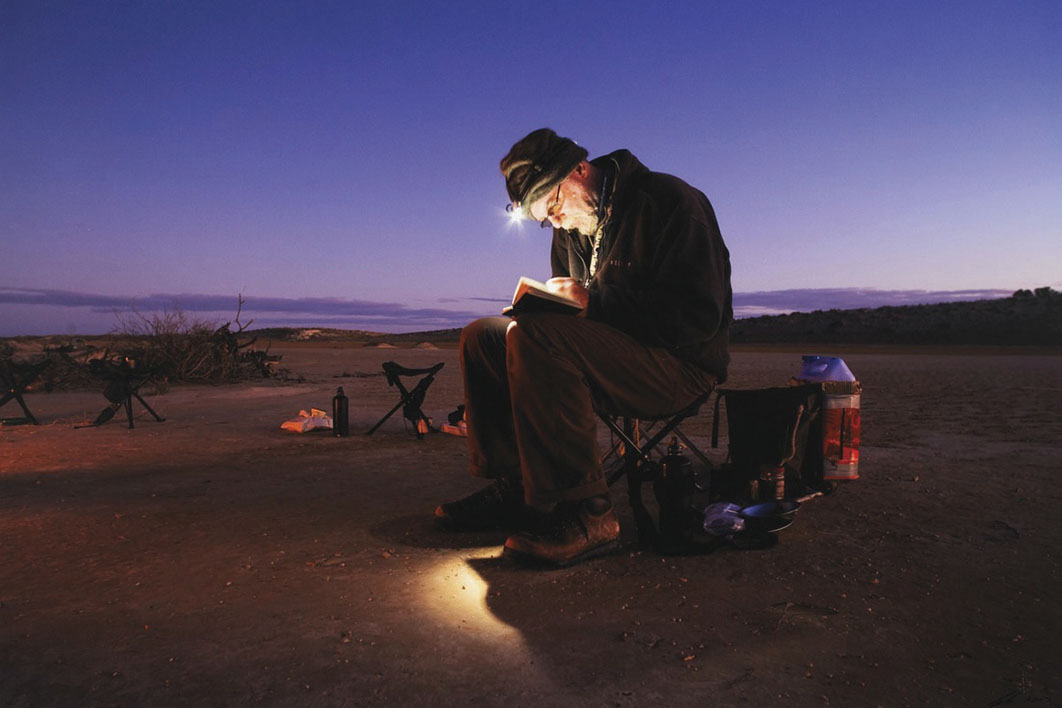

Crouched in the red sand, handling a stone artefact with an arc of blue desert sky above him, Mike Smith is at home. This connoisseur of deserts, who revolutionised our understanding of the human history of Central Australia, has a discerning eye for the distinctive character of Australia’s Red Centre. His new book, The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts, published in March by Cambridge University Press, is the most important exploration of Australia’s ancient human history since John Mulvaney’s The Prehistory of Australia was published forty-four years ago.

“The discoverers, explorers and colonists of the three million square miles which are Australia,” Mulvaney wrote in his revolutionary opening sentence, “were its Aborigines.” He was writing at the end of the 1960s, a decade that he called “the deluge,” “the golden years,” “the Dreamtime” of Australian archaeology. Australians had finally confirmed that they lived on a continent with a truly ancient human history and suddenly found themselves gazing into a dizzying abyss of time.

Settler Australia has a history of ambivalence about intimations of Aboriginal antiquity and adaptability. Colonists were reluctant to acknowledge the depth of belonging of a people whose continent they had usurped. This means that any broad understanding of the human antiquity of Australia is a relatively recent and dramatic event that rested on the twin revolutions of professional archaeology and radiocarbon dating, both of which emerged in local practice in the 1950s and 1960s. Since that time, archaeological dates for human occupation in Australia have deepened from 13,000 years before the present (secured by Mulvaney at Kenniff Cave in Queensland in 1962) to over 30,000 years at Lake Mungo by 1970, to over 40,000 years at several sites by the 1980s, and then a likely 50–55,000 years determined by Rhys Jones, Mike Smith and Bert Roberts at Malakunanja II in Arnhem Land in 1989. “No segment of the history of Homo sapiens,” wrote Mulvaney, “had been so escalated since Darwin took time off the Mosaic standard.” It turned out that “the timeless land” was actually replete with time – and dynamic with human history.

Mike Smith’s career unfolded during this period when settler Australia was coming to grips with the deep Aboriginal past – and one of the archaeological revelations of the mid to late 1980s came from his own excavation at Puritjarra in western Central Australia. Smith had arrived in Australia from Blackpool, England, in 1961, aged six, the son of “ten pound” British migrants. For a few months during his primary school years, his father’s work took young Mike to remote Ceduna, the last major settlement before the Nullarbor Plain, with a population that was mainly Greek and Aboriginal. In this town of sand and cinder-block houses, Mike remembers collecting lizards and playing in rusty cars. He began to develop a taste for arid Australia: “the smell of the country, that light, the sense of openness and adventure.” Although he knows Australia as few do, Smith has never lost his British accent and has been known to treat it humorously as a “speech impediment.”

In late primary school he made a conscious decision to pursue a career in archaeology. He had corresponded with staff at the South Australian Museum about his reptiles, and by the age of fifteen he was asking to join a museum dig at Roonka on the Lower Murray and then one led by Hungarian émigré Alexander Gallus at Koonalda Cave in the Nullarbor. Carrying buckets at dig sites enabled him to meet the well-known archaeologist Rhys Jones, “a very inspirational man” who was happy to “talk to a kid.” By the time Mike came to the Australian National University in 1974 to study archaeology with John Mulvaney, he already had substantial field experience and was “hooked on Australian work.” In an interview for the National Library of Australia last year, he recalled the excitement of this period: “There were new discoveries every six months or so. And this combined with my own personal exploration of the continent. I was interested in geography; I was interested in the structure of a continent. And archaeology was my means of travel as much as anything else.”

Soon after finishing a masters degree, he got a job as field archaeologist at the Northern Territory Museum in Darwin where his “amazing brief” was “to engage in the field survey and excavation of Aboriginal and Macassan sites in the Northern Territory.” By the beginning of 1982 he was keen to move his base to Alice Springs, for the Red Centre had got in his blood. Ceduna had played a part in seducing him to aridity, but so too had visits to the South Australian Museum, where he gazed, fascinated, at “those older museum displays of Arrernte ceremonial costumes: the big, conical, feather-down headdresses with the feathers glued on with blood.” They seemed to depict a society that was not just exotic but totally alien, and yet the setting was his own continental backyard, that great alluring heart of desert that was part of the geographical imagination of South Australians. He glimpsed the mysterious world captured in Songs of Central Australia by the anthropologist T.G.H. Strehlow, and in the writings of Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen. He realised that “there was a rich, exotic Aboriginal cultural and political system out there. Central Australia is where I wanted to be.”

Smith wanted to test the generally accepted belief that Central Australia had been occupied by people only after the end of the last Ice Age. He needed a site that would make full use of his stratigraphic skills and surgical precision, a site that would be a “palimpsest of different deserts,” of past climates, geomorphic processes and cultural systems. He searched for years. The desk he inherited in Alice Springs had a pile of slips of paper in a drawer, one of which noted the existence of a large cave near Mount Winter in the Cleland Hills. Nothing more than that, but it was a vital clue. “But it took a lot of time to work out quite how to get out there and also where to go,” he recalls. Finally, with the help of historian Dick Kimber and rock art scholar Grahame Walsh, Smith was able to get to the remote Cleland Hills.

It was 3 August 1986 and they had just one morning to search sixteen kilometres of the range for the great hollow of a cave. Kimber walked south and Smith walked north. Mike walked and walked, and finally came round a corner of the outcrop, and then he saw something. “I could see these shadows at the base of an escarpment and it looked like it could be something quite big,” he wrote later. “So I walked over and there was this absolutely huge rock shelter, I mean enormous! A big opera shell structure. I have not seen anything like it since; it is absolutely the most remarkable site. I knew that was the site, it matched the description. It was the site that would warm any archaeologist’s heart. I knew this was a site that would give me a good sequence.”

“A short time later I met Mike,” Dick Kimber recorded. “He was elated. He had found the cave.” Smith had found Puritjarra, the site that would occupy much of his archaeological attention for the next quarter-century.

After Lake Mungo, Puritjarra is the single most important archaeological site in the Australian desert – not simply because of its intrinsic values, but also because of the time invested in its analysis. Thanks to Mike’s enduring commitment, it is one of the most carefully documented and dated sites in Australia. Puritjarra deepened the chronology of human history in the centre of the continent from 10,000 to 35,000 years, a period at least as long as modern humans have occupied Western Europe. Modern Australians began at last to realise that they were the inheritors of a human saga of global significance, a drama in which people survived Ice Age droughts in the central Australian deserts and managed to sustain civilisation in the face of massive climate change. Puritjarra is a place that Australians should revere.

Smith’s new book, which was launched at the National Museum of Australia in March, tells the story of Puritjarra – but also of all Australia’s arid lands. It explains and analyses the social and environmental history of the largest area of desert in the southern hemisphere. In reality, inland Australia is made up of a variety of deserts with great natural diversity – it is a vast region of drylands, dune fields, stony plains, ephemeral rivers, salt lakes and desert uplands, all quite different from the deserts of southern Africa, South America or North Africa. Smith’s book is a product of his life-long commitment to understanding this unique region. He has worked on an outback sheep station as a roustabout, hiked and driven the country as a field archaeologist, walked with a string of camels through remote country west of Lake Mackay and in the Simpson Desert, and dug carefully into desert sands. He sees himself as “holding the region up to the light like a gemstone, turning it around and watching its personality refracted in different ways.” This is a scientific work that is also literature.

There have been many outstanding studies in Australian archaeology in the half century since Mulvaney’s book; in fact, I feel we are blessed, as Australians, to have so many gifted archaeologists to guide us in our quest to understand the deep past of this continent. But Mike Smith’s book is notable for its careful absorption, acknowledgement and encapsulation of all the scholarship that precedes it. Through his synthesis, which is built on the foundation stone of his own original archaeological research, he makes us see Australian human history anew.

Smith was a student of Mulvaney and, like him, is a cultural historian as well as an archaeologist. Both these men see archaeology, with its palaeo-environmental data and its science of stratigraphy, as ultimately a humanities discipline. Although Smith established some of our oldest dates of human occupation, he believes that the best way to demolish the “timeless” metaphor that stalks ancient Australia is to piece together a complex, contoured history of social and environmental change from the first arrival of people in Australia to the present. A nuanced narrative of change through millennia ultimately conveys depth better than dates. In The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts, Smith works from the ancient past forwards and from the ethnographic and historical present backwards, and he produces a rich history of Australian humanity.

As well as connecting Australians to the human exodus from Africa, he proposes an Australian history of constant social change such that, for example, “much of the fabric of desert tradition” encountered by Europeans might be no older than 4000 years. It turns out that the classic ethnographies of a “timeless” people actually described desert societies that had survived, and been transformed by, an environmental roller-coaster and were undergoing accelerating cultural change. The deep past is shown to echo powerfully in the contemporary cross-cultural history of people, politics and possession.

In 1996, reflecting on the Australian time revolution, archaeologist Denis Byrne wrote a brilliant essay called “Deep Nation” for the journal Aboriginal History, in which he meditated on what it means for a settler nation to embrace as its own the past of a culture it once rejected as a savage anachronism. Byrne analysed how the discourse of depth – which is such an appropriate and seductive metaphor – has sometimes inadvertently led to archaeology’s disconnection from the living Aboriginal present and to an essentialism of a timeless, traditional Aboriginal past. Byrne argued that, “if archaeology were to cease concerning itself with the nation’s desire for depth, it might rise, as it were, to the surface.” By “surface,” he meant that relatively horizontal (post-1788) terrain “where duration is measured in terms of generations rather than millennia.” Such practice would cease to locate real Aboriginality in the pre-colonial past, and would refuse the obsession with cultural purity. Writing almost two decades ago, Byrne did not foresee, perhaps, how quickly this apparent binary might be transcended, and how effectively the depths and the surface might be united in one remarkable vision.

Mike Smith’s career and oeuvre help us to think through these challenging and exciting dilemmas of our time. He sees himself as part of the generation of archaeologists who picked up the baton from John Mulvaney and Rhys Jones and completed the basic archaeological exploration of the continent: “in terms of finding the corners of the room, that was a job that my generation finished, completed.” He is also part of the first generation of Australian-trained archaeologists. And he feels privileged to have been among the last to have travelled and worked with Aboriginal people who grew up in the bush without major contact with Europeans. His reflective practice offers us an enabling window onto archaeology in the period of escalating human timescales and resurgent Aboriginal politics.

Known affectionately at the National Museum as Dr Deep Time – a man so enamoured of stratigraphy that he got a gravedigger’s certificate through TAFE to learn the ins and outs of timber shoring – Mike has also sifted the surface sands of his beloved deserts with meticulous historical care. In an earlier book, Peopling the Cleland Hills (2005), he gives us a remarkable modern history of a frontier, drawn from documents, memories and conversations-in-place. And he finishes The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts with a cultural history of the last millennium. He believes it is important to retain a feeling for the contemporary cultural landscape that swirls around the sites he studies, and so in Peopling the Cleland Hills he uses Puritjarra as a place from which to view the modern social exchange and disruption generated across Kukatja country by the European invasion.

Although his focus in that book is the last century-and-a-half, there are tens of thousands of years of history implied in his gaze. Rather than following large-scale events themselves, pursuing them off-stage, as it were, Smith keeps us grounded in place and we see them flicker past or we feel the ripple of their distant impact. There is a kind of Aboriginal patience in this earthed archaeological view – in this Ice Age inheritance, this steady, embedded watchfulness over particular country. We can sense in that book, more explicitly than in any of Smith’s other work, how intimately and even spiritually he has come to identify with the desert and its modern people. This is surely a source of the powerful poetic vision that illuminates his science.

The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts fits within a grand tradition of Australian desert literature of which Mike Smith is keenly conscious: Ernest Giles, Baldwin Spencer, Frank Gillen, J.W. Gregory, C.T. Madigan, T.G.H. Strehlow, H.H. Finlayson and Francis Ratcliffe, to name a few. A lineage of desert authors and titles is invoked in this study and every issue is elucidated through an intellectual history of its origins and evolution. You only have to talk with Mike Smith for a few minutes to know his magic with words, phrases and metaphors. It is no surprise that his book glows with poetry – I mean the poetics of hard-won hard facts beautifully presented, the poetics of disciplinary insight and logic, and the poetics of lucid prose.

Recently Smith donated his “Desert Collection” of books to the library of the National Museum of Australia. There they are shelved separately in a beautiful room. And Smith’s book now slips into the left-hand end of the top shelf. It is there at the very apex of a spine of ideas and words, a sweet acknowledgement of the donor. But the book is also, symbolically, the sum of that collection, for it is a culmination of it, a distillation of all that has gone before – and more.

Smith has written The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts for several audiences: for the world archaeological community, for his fellow Australians, and especially for the people who welcome him in their desert country. He has worked with three generations of the Multa and Tjukadai families responsible for the Cleland Hills. In his 2012 National Library interview, Mike had this to say to his Aboriginal friends: “This is a rich history. It is something that sits next to the Dreaming. It doesn’t displace it, it doesn’t replace it, but it’s a rich history here, it’s something to be proud of… It’s been my privilege to work on this history, but in a sense it has also been my gift.”

The American archaeologist Richard Gould, whose important work at the Puntutjarpa rock shelter in the Western Desert in the late 1960s is described in Smith’s book, is quoted on the back cover of The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts, declaring it “a ‘must’ for anyone seriously interested in Australian cultural history.” He’s right. And note that Gould does not use the words “archaeology” or “prehistory” or “Aboriginal.” I think there is a kind of coming of age of a settler nation in being able to say that this is, quite simply, a landmark work in Australian cultural history.

Mike Smith begins and ends the book with the Arrernte ceremonies performed for Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen in the summer of 1896, those “exotic” rituals which first fascinated him as a boy visiting the South Australian Museum. He calls the ceremonies “a watershed event in anthropological literature, a profound intellectual exchange between elite members of two very different societies.” He explains at the end of the book that he has tried to approach the 1896 ceremony from the other side, “reconstructing the long history that shaped the world of the Arrernte elders sitting across the ceremonial ground” from the observing Europeans. This is the other side of the frontier in a whole new sense. In 1981, Henry Reynolds wrote a revelatory book about the often-violent encounter between Aborigines and settlers on Australia’s grasslands, and he used that metaphor as his title. Here the archaeologist Mike Smith, with rigorous science and inspired humanism, imagines the other side of the frontier not just in space, but in deep time too. •

The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts

By Mike Smith | Cambridge University Press | $37.95 | 400 pages