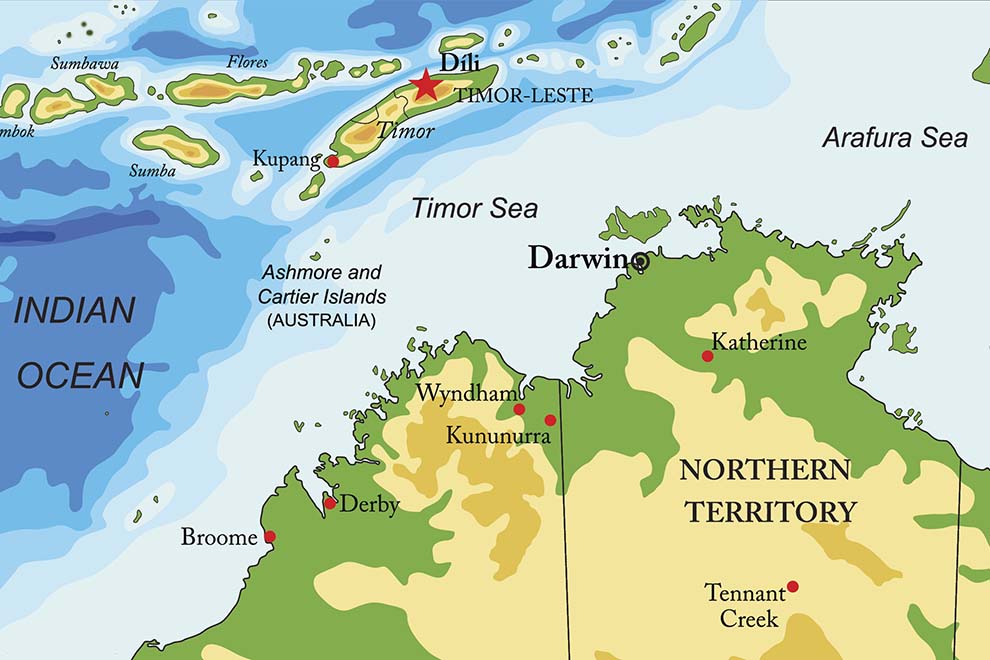

Election year in Timor-Leste got off to an unexpected start with Monday’s joint announcement that the government in Dili would terminate its 2006 treaty with Australia covering maritime arrangements in the Timor Sea. The decision, which Australia said it would not contest, opens the way for fresh boundary negotiations between the two countries.

Aside from provisions for sharing the proceeds of under-sea resources, the key feature of the 2006 agreement – known as CMATS – was a fifty-year moratorium on negotiations to determine the boundary between Australia and Timor-Leste. Instead, the two countries negotiated a series of revenue-sharing agreements, known as “provisional arrangements” under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS.

Monday’s announcement is especially significant because it is the first time since the restoration of East Timorese independence in 2002 that Australia has publicly committed to negotiating permanent maritime boundaries. Malcolm Turnbull and foreign minister Julie Bishop had consistently rejected calls for boundary talks and were voicing their support for CMATS as recently as late last year, so the turnaround is a significant step.

Several factors help explain the change in Australia’s position. For one, the 2006 treaty had been tarnished by allegations that Australia had spied on the East Timorese negotiating team in 2004. The reported evidence of a former ASIS agent, “Witness K,” provided grounds for Timor-Leste to challenge the treaty, invoking the Vienna Convention’s principle that negotiations should take place in “good faith.” Monday’s joint announcement is, in effect, an acknowledgement that Australia wants that case to end.

Equally significantly, last April the government of Timor-Leste initiated compulsory conciliation proceedings under UNCLOS with the aim of concluding permanent maritime boundaries with Australia. Australia’s opening legal gambit – the claim that the CMATS treaty had already settled the border dispute – was roundly dismissed by the proceeding’s judges, who found that Australia’s obligation to settle the boundary survived the treaty, despite the purported moratorium. Having lost this argument, Australia had little further use for CMATS. Monday’s announcement demonstrates that the UN-auspiced conciliation process is working, and highlights the importance of the principles and institutions of law in these disputes.

The third factor was the dispute between China and its neighbours in the South China Sea, which raised the regional profile of law in boundary disputes. In that case, Australia urged China to follow the rule of law, as represented by the decision of the tribunal formed under UNCLOS. The contrast with Canberra’s own behaviour – its refusal to discuss a boundary in the Timor Sea and its withdrawal from the dispute-settlement provisions of UNCLOS shortly before East Timorese independence in 2002 – has created something of a public relations problem for Australia.

While Australia’s new commitment to negotiating a permanent maritime boundary is overdue and welcome, this doesn’t mean that negotiations will be conclusive or rapid. The two sides are likely to start from very different positions on where a boundary should be settled. While Australia may find it difficult to maintain its “natural prolongation” continental-shelf argument given the increasingly strong presumption of a median-line boundary in law, the process of negotiating frontier and lateral boundaries, and the consequent revenue arrangements, could be lengthy or deliberately drawn out.

It is also notable that the government’s pledge to negotiate a boundary does not go as far as Labor’s policy, which commits to ly binding dispute resolution if bilateral negotiation fails. In other words, Canberra hasn’t committed to the settlement of the dispute in accordance with law. Nonetheless, this week’s announcement is a positive step, and a clear endorsement of the UNCLOS conciliation process initiated by Timor-Leste. For its part, Timor-Leste is likely to drop the espionage case against Australia.

The key issue ahead is the division of royalties from the Timor Sea. Setting the boundary at a median point between the two countries would certainly lift Timor-Leste’s revenue from existing fields in the Joint Petroleum Development Area, which stands to rise from 90 per cent to 100 per cent. But these fields are heading towards the end of their lifespans, and the larger and as-yet-undeveloped Greater Sunrise field, which straddles the eastern lateral of the Joint Petroleum Development Area, is a trickier question. CMATS divided future rents over this field on a fifty–fifty basis, but the earlier Timor Sea Treaty, which prevails until the coming negotiations are concluded, gives just 20 per cent to Timor-Leste.

Though these are merely numbers on a page while the field remains undeveloped, and would be superseded by any fresh negotiations, they highlight how critical the final revenue details will be for Timor-Leste. The future placement of the eastern lateral boundary will therefore be of prime relevance. The East Timorese government has formal legal opinions suggesting it should receive a larger share of that field when the boundary is finalised. Herein lies clear potential for disagreement between the parties.

Of potential relevance to this question is Timor-Leste’s current maritime boundary negotiations with Indonesia. While these talks will start off on the north coast, it is the south coast determination that could have a wider impact – not least where the lateral boundary is set within their territorial waters, which could potentially influence its extension further south in any new division between Australia and Timor-Leste. Canberra also remains concerned that a median-line boundary, favoured by law since UNCLOS, could open up a challenge to the 1972 “continental shelf” border with Indonesia. This possibility can’t be ruled out, though it is fair to say that the political risks exceed the legal exposure, as there remains a very substantial difference between a border settled and observed for forty-five years and one that was never negotiated.

Less often posed are questions over the western lateral boundary of the Joint Petroleum Development Area. Longstanding fields like Corallina, Laminaria and Buffalo lie just outside it, but potentially within the future Exclusive Economic Zone of Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste has received no royalties from these fields, which have returned rents to Australia. Will a settlement of boundaries include compensation for lost royalties? These issues could arise in negotiations, and suggest that Timor-Leste will have cards to play in terms of trading off potential claims. Though understandings exist between the two governments relating to these matters, they could come back into play in fresh negotiations.

The coming negotiations won’t necessarily be conclusive; nor are they guaranteed to meet all of Timor-Leste’s aspirations. But this is a significant turning point in the dispute. It may also give pause to critics of the East Timorese government’s legal strategy.

Critics are less likely to resile from their critiques of the ambitious East Timorese plans for “downstream” processing of oil and gas on the country’s south coast, which remain out of favour with commercial partners like Woodside Petroleum. More broadly, the East Timorese government’s current approach to development, heavily focused on mega-projects and large-scale infrastructure spending, continues to attract criticism, as does the sustainability of the country’s sovereign wealth fund, given current rates of annual budget expenditure.

While these matters tend to attract attention in commentary on the boundary dispute, they are separate issues, subject to increasing debate within Timor-Leste’s lively civil society itself, and are likely to feature in this year’s elections. •