I began my encounter with Vietnam in the 1960s, wondering why so many people there talked with such excitement about where they were and what they were doing in 1945–46. Puzzlingly, Vietnamese materials about that era proved very hard to find. I could find almost nothing in Saigon libraries or bookshops, but I did manage to locate a left-wing book store in Hong Kong that sold subscriptions to Hanoi periodicals, notably Nghien Cu’u Lich Su’ (Historical Research). One day in 1964 two FBI agents came to our Berkeley graduate student apartment to ask why I was receiving enemy propaganda in the mail. The following year, while researching student political agitation in Saigon, I was given a stack of confiscated Hanoi publications by Colonel Pham Ngoc Lieu, chief of the Republic of Vietnam’s National Police. These whetted my appetite, but were hardly the makings of a PhD project.

My 1968 dissertation and first book, Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885–1925, focused on the minority of Vietnamese who contested French occupation and colonisation during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They left a legacy of failures tinged with heroism, as well as a blunt challenge to the new generation of French-educated youth to learn from their mistakes. My second book, Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945, pursued the intelligentsia of this generation as it debated issues of ethics and politics, language and literacy, the status of women, lessons from the past, harmony and struggle, knowledge power and political praxis. These lively exchanges took place amid rapid socioeconomic change, repeated changes in French colonial policy, and finally the turmoil of the second world war. Not solely intellectuals, but other Vietnamese as well, became convinced that life was not preordained, liberation and modernity were open to all peoples of the world, and one could join with others to force change.

My third book, Vietnam 1945: The Quest for Power, tried to bring alive the events and explain the significance of what Vietnamese still call the August Revolution of 1945. First I canvassed the previous five years, when Vichy French, Japanese, Chinese, Americans, British, Free French, Vietnamese communists and Vietnamese nationalists all tried to control or influence events in Indochina. On 9 March 1945, the Japanese Army overturned the French colonial administration, which meant that France was removed from the contest for a vital six months. Vietnamese quickly discovered they could publish, organise and demonstrate in favour of national independence, so long as they did not hinder Japanese defence preparations. The anti-Japanese Vietnam Independence League, or Viet Minh, continued to extol Allied victories and denounce the “dwarf bandits” (giac lun), but mostly avoided confrontation in favour of popular proselytising and preparations for eventual revolt. In some localities, peasants raided rice granaries, seized landlords’ properties, incarcerated village headmen and caused district mandarins to flee for their lives.

News of Tokyo’s capitulation to the Allies on 15 August spread quickly across Vietnam, triggering scores of exuberant demonstrations, seizures of government offices, burning of documents and formation of revolutionary committees. Members of the Indochinese Communist Party, or ICP, took control in Hanoi, Hue, Saigon and some provincial towns in the name of the Viet Minh, while elsewhere bands of young men and women accomplished much the same thing of their own volition. It was a moment when everything seemed possible, when people felt they were making history, not just witnessing it. Some Japanese commanders gave local Vietnamese groups stocks of arms and ammunition they had seized from the French. Viet Minh cadres, having identified themselves with the Allies, now enjoyed a major propaganda advantage over groups that previously had cooperated with the Japanese. As a result, most youth groups were soon waving Viet Minh flags and repeating available Viet Minh slogans, even though they had no contact with higher Viet Minh echelons and no familiarity with the overall Viet Minh platform.

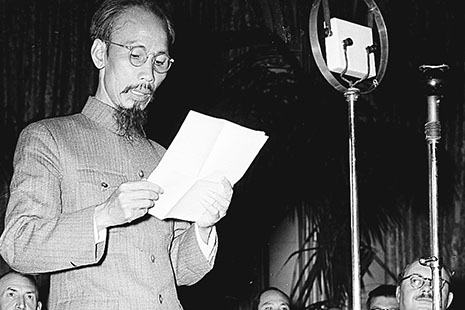

Vietnam 1945 ends on 2 September, when big crowds gathered in Hanoi and Saigon to celebrate Vietnamese national independence. In Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh, provisional president of the new Democratic Republic of Vietnam, read a short independence declaration designed for as well as domestic consumption. Loudspeakers ensured that the audience not only heard what Ho and others had to say, but also responded loudly and eagerly on numerous occasions. After Ho brought the meeting to a close, Viet Minh contingents marched downtown, disbanded and joined in the general merriment until the hour of curfew. In Saigon, however, members of the Southern Provisional Administrative Committee had just finished addressing the crowd when shots rang out on the periphery, people stampeded, and mobs proceeded to hunt down French civilians, killing several, beating up others, and terrorising the rest. These two denouements, one orderly, the other anarchic, showed how the popular upheavals of August could propel Vietnam in starkly different directions. People sensed that their lives had changed irrevocably, yet no one could predict what the next week might bring, much less subsequent months and years.

My new book, Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution, focuses on events of the next sixteen months, when Vietnam’s future course was largely determined. Between September 1945 and December 1946, the Democratic Republic began to function, a national army was created, the Japanese, British, Americans and Chinese faded from the Indochina power equation, and France and the Democratic Republic manoeuvred vigorously to gain advantage. A second famine was mostly averted, French properties were appropriated and informal fundraising campaigns were used alongside formal tax levies. The ICP gradually extended its control over local Viet Minh groups, then pressured other parties to either accept its hegemony or be treated as traitors. Millions of men, women and children joined local associations for the defence and development of the nation. Ho Chi Minh spent the summer of 1946 in Paris trying to negotiate a settlement, but tensions increased at home. This culminated in French seizure of Haiphong in November, and attacks by Democratic Republic forces in Hanoi and elsewhere on 19 December. The First Indochina War would last another seven-and-a-half years.

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam survived and eventually prevailed largely because of the unprecedented participation of ordinary citizens, most of whom never fired a shot in anger. Why and how people took part are questions I approach from multiple angles. Clearly individuals had other aspirations besides defeating the enemy. The Democratic Republic took on many functions that had no direct bearing on the armed struggle, although it usually justified these expansions in resistance terms. The ICP also used the war to justify its grabs for power. Amid all these attempts to control affairs, war and revolution produced a host of unintended consequences that Vietnamese had to live with for decades thereafter.

Often I have asked myself the same question that Thomas Carlyle did when he embarked on his history of the French Revolution: what was it like to be there? Lacking Carlyle’s dramatic flair, I cannot evoke a Vietnamese Mirabeau or Robespierre. Well-known personages like Ho Chi Minh, Vo Nguyen Giap, and Truong Chinh do tread the stage, yet I’m equally interested in the teenage Viet Minh activist, the aggrieved village petitioner, the provincial committee chairman, the former colonial fonctionnaire, the eager journalist, and the high school pupil heading south to fight the French, armed only with a machete.

Archival dossiers, newspapers and books generated in 1945–46 have motivated me for years to get up each morning, tackle inconsistent evidence, find patterns but also contradictions, and then try to craft a historical narrative of human beings responding to and making events at this particular place and time. Most exhilarating has been the gouvernement de fait collection at the Archives National d’Outre-Mer, in Aix-en-Provence, seventy-eight cartons of Democratic Republic documents captured by the French Army in Hanoi in late 1946. It is one measure of the high-level confusion bedevilling the Democratic Republic on 19 December 1946 that government clerks were still at their desks in Hanoi only two hours before Vietnamese attacks began; they then failed to destroy thousands of dossiers lodged in the basement of the Northern Region Office before leaving.

If it had been feasible to write this book twenty years ago, Vietnam watchers would quickly have recognised the political rhetoric, the policy assumptions and the attitudes of people in the late 1940s. Now a lot has changed. Amid today’s mobile phones, vibrant markets, foreign investors, Nike shoe factories and nouveau riche families, stories of war and revolution may seem embarrassingly antiquated. For young Vietnamese it is still necessary to learn enough about the anti-French resistance to pass school examinations, but beyond that the period appears distant and inconsequential. For many young scholars of Vietnam in the West there seems to be an assumption that amid all the Communist Party propaganda nothing of continuing significance can be found out about the Democratic Republic, the Viet Minh or the resistance.

Yet many of the state institutions created in the late 1940s remain intact in Vietnam today, as do popular beliefs in modernity, efficiencies of scale and centralisation of power. Just below the surface, fears of foreign intervention or manipulation persist as well. The party continues to justify its dictatorship by reference to alleged achievements in the August 1945 Revolution and anti-French resistance. Critics of the party sometimes harken back to the relatively open press of 1945–46, the January 1946 national elections, the Democratic Party, and the November 1946 constitution, yet they lack detailed knowledge of events.

When the Vietnam History Association organised a seminar in Hanoi in 1995 to discuss my Vietnam 1945 book, the passage to which a number of participants took exception was the assertion that “the only truth in history is that there are no historical truths, only an infinite number of experiences.” By contrast, only one person criticised me for underrating the role of the ICP in events, while several others chose to recount personal experiences in 1945 that supported my argument, without saying so explicitly. Today, younger generations in Vietnam seem less wedded to historical truths, more willing to question dogma. I look forward to lively discussions. •