He had only been prime minister for a year, but Gough Whitlam’s efforts to empower Australia’s first people had disturbed and angered Aboriginal people and whites alike. The missteps of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs had received extensive media coverage, and included a costly turtle-farming proposal that – as the press reported – had gone belly-up in the Torres Strait. Radical Aborigines saw the department as disingenuous and slow, while conservatives thought its intentions misguided or even dangerous.

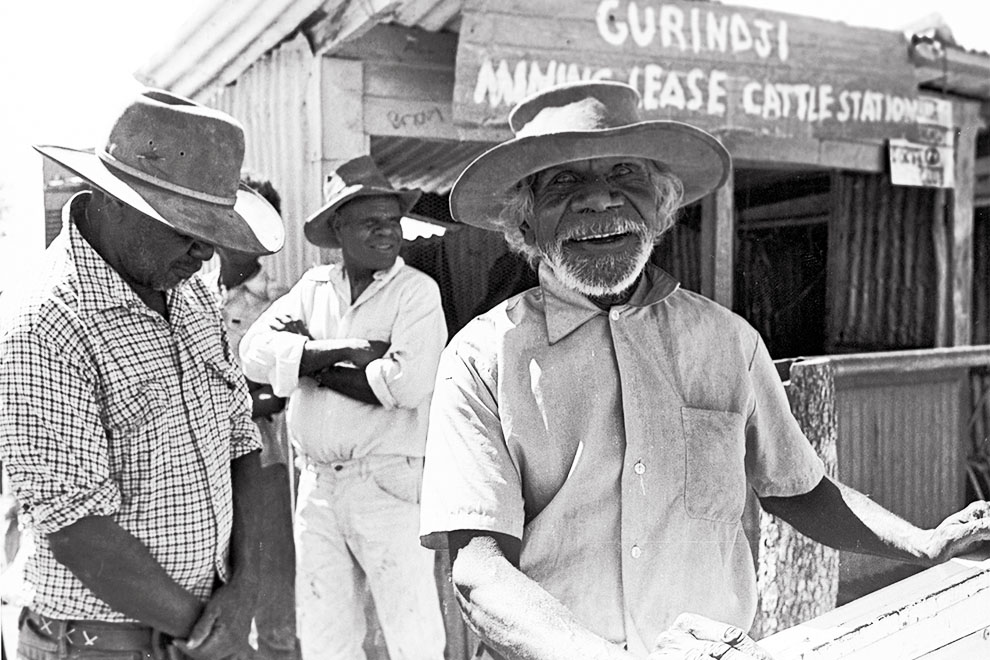

The people most able and willing to take up opportunities flowing from the DAA’s policy of “Aboriginalising” its workforce were English-speaking, urban and politicised. The radical agenda of some of these activists (and even their identification as Aborigines) was criticised by paternalistic whites, including former staff of the NT Welfare Branch still working in the department. “Traditional” Aboriginal people like the Gurindji were mostly untouched by these controversies, but in 1974 the elders at Daguragu – formerly the Wattie Creek camp – were also drawn into the fray.

One person inflaming these controversies locally was Philip Nitschke. Nitschke, an opinionated physics graduate of Flinders University, had been given a government-funded gardening job in the Gurindji community by two elders, Lupngiari and Mick Rangiari. Since he’d arrived several months earlier, Nitschke had embraced his role as gardener, scribe, lobbyist, mechanic and tutor with huge energy. His efforts to publicise the Gurindji’s quest for land made those of his predecessors seem half-hearted. But unlike other activists who had attempted to maintain good relations with kartiya, or whites, in the area, Nitschke had no hesitation about fronting Europeans on behalf of the “track mob” as he saw fit. His confrontational style quickly enraged the settlement’s new DAA adviser, Trevor LaBrooy – and its other white residents.

When LaBrooy arrived to replace his friend Len Ibbetson in early 1974, the Victoria River was in flood. His “welcome” included being swept several kilometres downriver before burying an old Gurindji man’s body in the dark, soaked by driving rain. A principled public servant, LaBrooy had worked on Queensland’s notorious Palm Island Aboriginal settlement. Finding the policies he was expected to enforce there unfair, he had petitioned the then Aboriginal affairs minister, W.C. Wentworth, over lunch about other work, and was offered a job by Harry Giese in the NT Welfare Branch.

As a justice of the peace who believed strongly in the rule of law, loyalty to the government and respect for “common decency,” LaBrooy was Philip Nitschke’s nemesis. To the young firebrand then flirting with anarchism, LaBrooy’s Dutch–British Ceylonese background was a sign of his “colonialism.” Although both men were on the DAA’s payroll, serious altercations occurred within weeks.

Like the Gurindji, Nitschke was dependent on the settlement’s services and needed LaBrooy’s goodwill. When a hunting rifle seemingly went missing in the post – which was being managed by Anna LaBrooy, Trevor’s wife – Nitschke angrily accused her of sabotaging Daguragu. The new superintendent was so enraged by this attack that he “bum-rushed” the younger man from his office with a well-aimed kick. Afterwards, when Nitschke threatened to dispose of him violently, LaBrooy – a former big game hunter – responded in kind.

The young activist was soon disliked by other whites in the area, too. Scottish nursing sisters Margaret and Bernadette Glass had just arrived at the settlement (and Australia), and although they were disconnected from local politics, found themselves in Nitschke’s sights. When he angrily told them to improve their service at Daguragu, the sisters called for LaBrooy to physically evict him from their clinic and filed a complaint. The nurses’ union spokesman doubtlessly had Nitschke in mind when he referred to “a new kind of… left-wing paternalism.” “The revolutionaries think they are going to take over,” he went on. “Some of the people implementing the government’s policy of self-determination are stirring things up. Some are employees of the ministry, and I think they should be sacked.”

By this point, Whitlam’s Aboriginal affairs minister, Jim Cavanagh, had received a stream of complaints and claims and counter-claims from the combatants at the Vestey family’s Wave Hill station. He defended LaBrooy, pointing out that “Mr Nitschke’s own inexperience and lack of training may well be an important factor in the situation.” Unbeknown to the Gurindji’s new adviser, the DAA was considering terminating his employment.

The conditions were certainly challenging, and although they were on better pay than the Gurindji, Nitschke and the nurses were doing it tough. In 2007 Nitschke remembered:

The first wet [season] we went through was pretty hard going, the bloody hut was awash with water. It was as hot as hell, there [were] twenty centimetre centipedes hurtling across the floor, sick dogs [were] everywhere, people were diseased. We were bloody trapped for a long period of time when the river was up… I don’t want to overstate this, but it was tough going.

According to local NT Legislative Council member Goff Letts, the nurses were living in

an undersized caravan with a leaky roof and a [tiny] refrigerator… They wash their clothes by hand… Their air-conditioning has been broken down for some time [and] there is no toilet or shower for them… They are in such poor circumstances that the Aboriginal people themselves have built them a bush shelter…

Daguragu’s elders were pleased enough by Nitschke’s work, but the fights erupting among the kartiya troubled them. Elder Vincent Lingiari, ever mindful of the Gurindji’s need to maintain good relationships in the region, attempted to prevent Nitschke from visiting nearby Wave Hill station. His concern was warranted; within months, the station manager Ralph Hayes threatened to “punch Nitschke’s head in.”

Hostility towards Nitschke even played out in the Gurindji’s camp. One night “Lynnie” Hayes (brother of Ralph), their old friend Sabu Sing (a mixed-race stockman who was raised on Wave Hill station by its manager, Tom Fisher) and the local policeman arrived for a “friendly beer” with the Gurindji. As the alcohol flowed, the visitors turned nasty. A senior Gurindji man, Pincher Nyurrmiarri, warned Nitschke that unless he left his camp, he would be attacked by irate whites. Nitschke watched from the darkness as the drunken whites came over to his camp:

My father [who was visiting] came out of the tin shed, and he stood outside where the fire was burning. I could hear the voices through the night, saying “Where is your shit-stirring son? We’re going to teach him a lesson.” My father said “I don’t know, he’s gone.” Then they started to give [him] rather a hard time, knocking him around.

Another senior man, Jerry Rinyngayarri, a teetotaller, arrived in the nick of time, and asked the visitors to leave. They got into their Toyota and issued a warning before driving off: “The weak bastard, we’ll get him one day.” Nitschke – who also received death threats – was inclined to take them seriously.

To encourage greater Aboriginal participation in government decision-making, the DAA had created a new National Aboriginal Advisory Consultative Council, or NACC, in a matter of months. The council was slated to be a key component of Aboriginal self-determination, and hopes surrounding the new body were high. At a meeting in Batchelor, Gurindji and other delegates were told they would “get a truly representative Aboriginal body, one big powerful voice to speak to the government.”

When the NACC assembled in Canberra in February 1974, its new councillors dictated their agenda. They requested far greater powers, an enormous pay rise, and reserved seats for Aboriginal people in parliament. It was not the “advice” the Labor government had wanted, and Cavanagh responded like an overbearing parent. The council, in turn, called for his resignation.

This clash at the heart of the government’s self-determination project – and the minister’s barely disguised dislike of “urban,” political Aboriginal people – put him on a collision course with Charles Perkins, the high-profile former activist who now headed the DAA’s liaison branch. Perkins, who had been given the job of creating the NACC, was unbowed. He told a national television audience that the minister had “as much understanding of Aborigines as of flying to the moon.” Coming on top of other misdemeanours, this transgression prompted departmental head Barrie Dexter to suspend Perkins.

Dexter’s takedown of the most powerful Aboriginal person in the nation increased the ire of new Black Power groups in the south. Despite his lobbying for land rights with the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, Dexter received death threats and was put under a twenty-four-hour police guard. The minister, Cavanagh, was also living with a security detail. In this environment it was not completely surprising that the DAA’s Canberra offices were stormed by three Kooris, one carrying a gun. Their leader, Bobby McLeod, had freshly returned from Wyndham, some 400 kilometres from Wave Hill, and was desperate about his people’s suffering. Finding that Dexter was out, McLeod and his friends held two senior ex-Welfare bureaucrats hostage instead. Perkins was called by the vigilantes to defuse the situation and, after talking down McLeod, went home with the gunman’s unfired bullets in his sock.

With Perkins inflaming a mutiny in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, the weekly Nation Review described the operations of the department as a “cops and robbers saga played out each day… with ever-increasing drama.” Another reporter described “open hostility between whites and blacks” and a rift that existed “from the very lowest position to the very highest.” According to Nation Review, things were so strained that when an Aboriginal staffer “floored a white in the department with a haymaker [punch], nobody was surprised.” At Wattie Creek, Philip Nitschke saw Perkins as a hero fighting the state, and encouraged him on the Gurindji’s behalf.

Nitschke and LaBrooy’s complaints about the management of the Muramulla Gurindji Cattle Company and about each other prompted Cavanagh to investigate the situation for himself, in May 1974. When LaBrooy heard of Cavanagh’s plan to visit, he adopted a more conciliatory tone and lent the DAA’s rubbish truck to Daguragu. Pincher Nyurrmiarri saw it this way: “When minister bloke coming up, that superintendent a bit frightened, so he been clean up a little bit…” LaBrooy maintained the timing was a coincidence. Far from his generosity heralding an end to the conflict, though, disagreement about these matters lingers to this day.

When Cavanagh arrived with Barrie Dexter and Gurindji supporter Don Atkinson on 29 May 1974, the pair wanted to relay news to the Gurindji about their land request. Whitlam had bestowed a small horse paddock lease on the Aborigines the previous year, and Cavanagh would soon announce the government’s intention to excise all the country the elders claimed and buy it from Wave Hill station.

The authorities’ justification for buying the Gurindji a pastoral lease at a cost of roughly $160,000 ($1.2 million today) was simple: the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights was dragging on, and the DAA was under pressure to act. A consultant’s report had found that the area the Gurindji wanted was “suitable for the establishment of a cattle station [which] has reasonable prospects of achieving long-term commercial viability.” Evidence that the elders wanted to run cattle this way was scarce, but the government would not carve up Wave Hill station without the justification that a profit could be made from the resulting excision.

While Cavanagh’s flight was en route to Daguragu, Nitschke and the elders tried to ensure that they, not the “establishment reactionaries” at the settlement, would greet the VIPs. LaBrooy thwarted them, and he and Alan Thorpe (who was now the DAA works manager) met the minister’s plane. During the drive from the airstrip, Cavanagh asked LaBrooy if it was true, as the activists had reported, that he had assaulted Nitschke. When he heard the superintendent’s tale of manhandling the scruffy activist from Commonwealth property, Cavanagh tapped him on the arm, whispered “Well done!” conspiratorially, and broke into laughter.

Upon the VIPs’ arrival in the Gurindji’s camp, Nitschke requested an audience with the minister without LaBrooy or other “Welfare” (DAA) staff present. While Daguragu’s elders watched on in bemusement, Cavanagh asked Nitschke to leave as well. Eventually, two meetings between the elders and Cavanagh were agreed upon: one with Nitschke, and one with LaBrooy present. Lingiari politely listened as the pair aired their grievances to the minister, before he moved the conversation to the Gurindji’s land.

Barrie Dexter had bad news. First, he admitted it was likely to be another two years before the excision from Wave Hill station could be made, and second, he informed the Gurindji elders that should they muster any unbranded cattle from Wave Hill station they would face prosecution. Furthermore, the elders’ Muramulla operation would soon be limited to employing two people until they got their excision. In total, thirteen people would soon need to be laid off. All of this shocked Lingiari so much he could barely speak. According to Nitschke, the effect on the group was “shattering.”

In effect, Dexter had told the elders that if they wanted more government support, their enterprise would be locked into “caretaker” mode in the interim. It seemed the Gurindji’s land rights – if they were ever recognised – would be delivered in the distant future. The old men had tasted government generosity, but remained completely at the mercy of the schedule and requirements of the state. Nitschke sensed injustice:

The catch cry of “self-determination, control and acceptance of responsibility” has become one of the strongest weapons used against the people by the… establishment reactionaries. To exercise control, there must be money and power – to crap on about self-determination whilst hanging on to the purse strings is gross hypocrisy.

The stress Cavanagh’s visit placed on the Gurindji elders was enormous. After he and Dexter departed, latent divisions among the leadership group flared. Lingiari was rebuked for his passivity and deferral before the visitors. Pincher Nyurrmiarri “wrote” angrily, leaving out the invective he unleashed on the day, “Old Vincent didn’t tell him [Cavanagh] right story from his heart. Minister didn’t find out much from Aborigine at Wattie Creek, what’s been happening.”

Such criticism of Lingiari by members of his coterie would hasten talk of succession. While the elder defended himself, saying he had not wanted to upset the minister and his party, Aboriginal politics itself was changing. Lingiari’s civility and respect for authority was increasingly missing from Aboriginal affairs. Aboriginal people elsewhere in the county were becoming – like the more radical Nyurrmiarri and Mick Rangiari – outspokenly critical. •

This is an edited extract from A Handful of Sand: The Gurindji Struggle, After the Walk-off, published this month by Monash University Publishing.