Former prime ministers can be a problem for incumbent prime ministers – especially if they remain in parliament. Despite his “no sniping” pledge, Tony Abbott looks set to make himself an irritant for the man who displaced him, Malcolm Turnbull, if his belligerent forays into foreign policy are a guide.

History tells us that prime ministers go neither quietly nor willingly. One characteristic shared by almost all twenty-eight former Australian prime ministers is a marked reluctance to relinquish the office. After all, what does one do after leaving the top job? What else is there to aspire to?

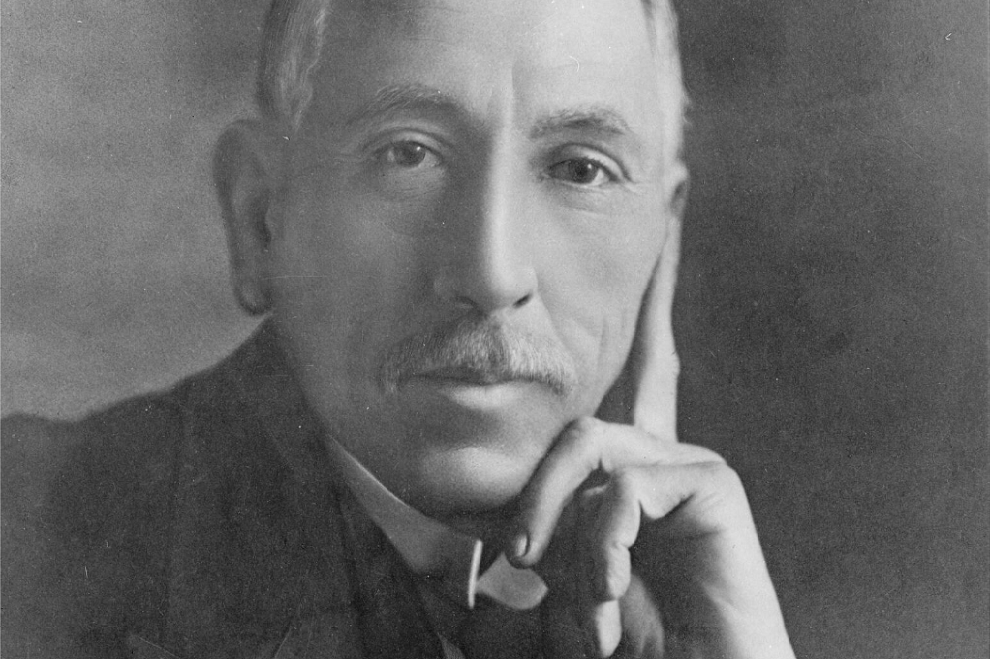

For some, it has been all about planning, plotting and intriguing to regain the top job. Billy Hughes, dumped by his own party in 1923, hoped time and time again that he would be recalled. He never was, but he spent the best part of his three remaining decades in parliament scheming and hoping.

Hughes was nothing if not tenacious in his pursuit of his old job. In 1929 he was instrumental in bringing down the man who succeeded him, Stanley Bruce, when he organised a parliamentary revolt that forced Bruce to an early, forlorn election. He had hopes that he might be chosen to replace Bruce; and he also, less realistically, hung onto the thought that the Labor Party (which he had left in 1916) might forgive him and restore him to its leadership. As a minister in the Lyons government during the 1930s, he liked to think he was still carrying the field marshal’s baton in his rucksack. In 1941, when the United Australia Party turned against prime minister Bob Menzies and deposed him, Hughes was there again, in deep with the plotters – and again hoping for a recall. It was Country Party leader Arthur Fadden who emerged to succeed Menzies, however; but still Hughes was not done, even returning briefly as leader of an exhausted UAP at the age of eighty.

Bruce, for his part, lost his own seat in 1929. But he soon returned, seeking to position himself for another tilt even after he had arrived in London as high commissioner. Like Bruce, James Scullin (1929–32), Robert Menzies (1939–41), Ben Chifley (1945–49), John Gorton (1968–71), Gough Whitlam (1972–75) and Kevin Rudd (2007–10) could never accept that losing the job was final. Menzies, of course, returned in triumph in 1949, Gorton’s hopes remained just hopes, Scullin, Chifley and Whitlam each fought on as opposition leader for one more election, and Rudd wrested back his old job after a long and ugly campaign.

Malcolm Fraser set a different precedent when he retired from parliament after losing the 1983 election. He was followed by Bob Hawke, who resigned after being deposed in 1991; Paul Keating, who resigned after losing the 1996 election; and Julia Gillard, who left parliament after losing the leadership in 2013. John Howard had the matter taken out of his hands when he lost his seat in 2007.

Kevin Rudd was the first ex-prime minister not to follow the Fraser precedent. After being dumped in favour of Gillard in 2010, Rudd devoted every waking hour (and possibly every sleeping hour as well) to finding a way back to the job he believed was rightfully his. Despite one challenge that failed and another that failed to happen, he eventually returned in 2013 to preside, briefly, over the carnage that was largely of his own making.

The death of a serving political leader always delivers a jolt to the system; it is not simply the loss of an individual and the accompanying bereavement, it is the sudden disruption of the power dynamics and the potentially destabilising effect on government and party – and of course the nation as a whole. As hitherto contained or concealed forces emerge, the prospect of a power vacuum and a scramble to fill it can shake the most rigid of hierarchies. However well-managed the transition, an element of uncertainty is always present, and its effects can continue to be felt long after the event.

The three instances of death in office all saw short-term prime ministers summoned by fate to fill the void until permanent replacements could be found, but even these three looked at ways of staying put: Earle Page in 1939, after the death of Joe Lyons, used his brief tenure to launch a vitriolic character assassination of Menzies to try to block his succession; Frank Forde in 1945, the shortest-serving prime minister, contested the ballot won by Chifley to succeed John Curtin; and John McEwen in 1968, after the death of Harold Holt, had some desultory discussions about staying on before the Liberals elected John Gorton.

Which brings us to Tony Abbott and his intentions. So far, he has not shown any inclination to follow the Fraser precedent; indeed, his demeanour suggests he is more of the Rudd persuasion, however delusional that appears to be. As Abbott liked to say as his prime ministership unravelled and leadership speculation mounted, “We are not the Labor Party.” And nor is he Kevin Rudd.

The differences between Abbott now and Rudd post-2010 are many. Rudd was not incompetent as prime minister, merely dysfunctional. He retained a solid core of support within his party while his successor had her tribulations with the uncertainties of minority government.

It was Abbott’s inability to hold a conversation with the electorate, combined with his increasingly bizarre political judgement, that eroded his support. Nothing has happened to change that view, and the government’s rapid recovery in the opinion polls since he was dumped more than vindicate the party’s decision. He is now thought to have at most five firm adherents in the Liberal party room, and even if Turnbull were to fall under the proverbial political bus, his replacement would not be Tony Abbott.

Former prime ministers will always receive a media hearing, but all too often their words, with Paul Keating a shining example, smack of relevance deprivation syndrome. It is not an excessively harsh judgement to see the Abbott prime ministership as a failure, in company with the negativity of Joseph Cook (1913–14), the ineffectuality of James Scullin (1929–32) and the embarrassment of William McMahon (1971–72).

Historians are by nature reluctant to make predictions, but in this case such reluctance can be confidently cast side: Tony Abbott will not return. •