And lo, as did King Solomon before him, the Honourable Justice Jonathan Beach of the Federal Court last week ordered the baby cut in twain. The Cormack Foundation, a $70 million investment fund, has been the subject of a long and bitter feud among Victoria’s Liberals. The party, under state president Michael Kroger, claims its resources are held in trust for the Liberals alone; the fund’s board, run by its eight shareholders — all big noises in the Melbourne Establishment — apparently feels otherwise, having cut off regular donations to the Libs in 2016 and directed funds to other right-wing parties at the last federal election.

The result has been a very public squabble over just who owns the money — one that has gone all the way to the Federal Court. There, Justice Beach, having pored over thirty years of letters, deals, oaths and entrails, found neither side to be quite right. He traced two shares to the Liberals — now worth just 25 per cent of the fund, and not enough to win any board seats — and left the rest with the independent directors (or perhaps that should be the secessionists?).

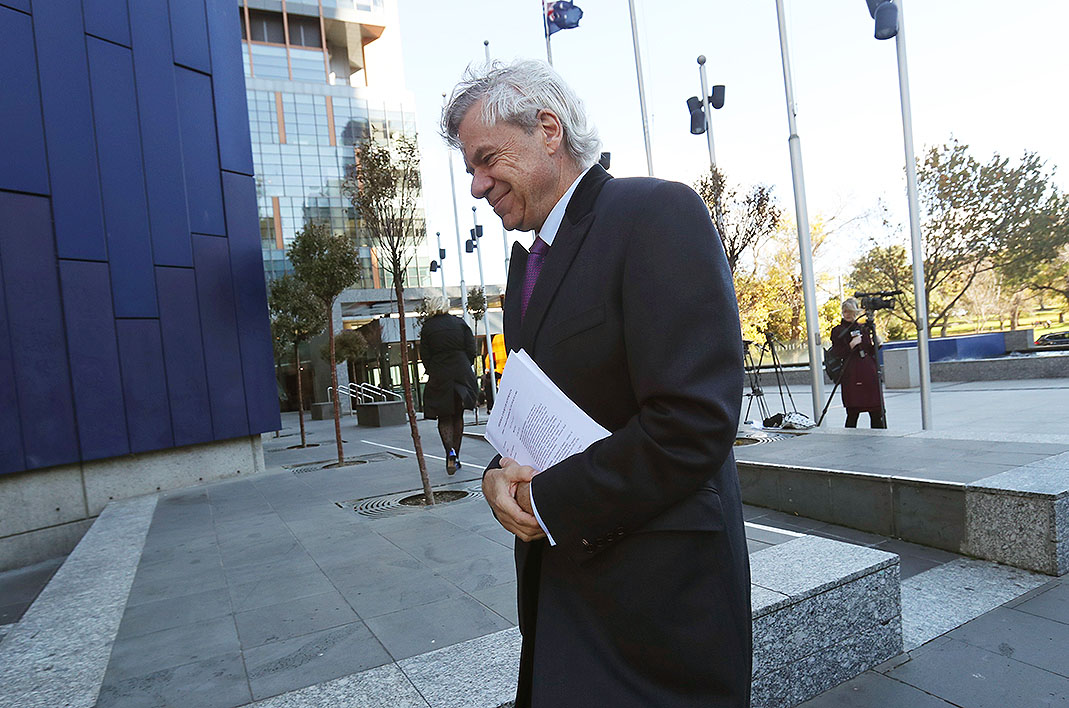

Both sides claim this as a moral victory, but in truth it is a stalemate. Round two of the Cormack bout commenced within minutes of the judgement, with Kroger issuing a demand via the assembled media that all remaining non-party shareholders quit the board and hand their shares to the party. The board, it appears, is disinclined to indulge him. After two years of bickering and brinkmanship, the battle for the Cormack kitty seems to have made no progress towards resolution at all.

The debacle puts the Liberals in bad shape for upcoming state and federal elections. The fund is usually its biggest donor, handing over millions to help make each campaign run smoothly. It also helps the party to maintain its Melbourne headquarters, a small CBD office block that Kroger is now looking to sell. As of last year, the official Liberal fundraising body, Enterprise Victoria, was also making a significant loss, with the party going into over a million dollars of debt to keep the operation afloat.

The problems don’t stop there. New donation laws being debated in state parliament would make it very difficult for the Liberals to restock their war chest. (Perish the thought that the Libs’ financial woes might have somehow influenced the timing of Labor’s donation reforms.) Of course, the party will find ways to finance its election campaign this November — donations will still come directly to head office, or perhaps to a fund set up by state leader Matthew Guy, controversially quarantined from the rest of the organisation. Smaller, electorate-based groups raise significant sums, some of which they give to party HQ, the rest to be spent on local campaigns or saved for a rainy day.

But even all added together, those funds are unlikely to make up for the money lost — in the millions — let alone the money that might normally be expected but might not arrive this cycle, especially given Kroger’s antagonising of the Melbourne Establishment during the Cormack battle and other imbroglios. In sum, the Victorian Liberals are in dire straits.

All this comes in the months leading up to a pair of elections, state and federal. Looking at the state electoral pendulum, Matthew Guy is at least a chance for seizing the premiership in November, assuming the party can find the money to campaign. Federally, with late 2018 also a fair bet for an election, the attention tends to focus on marginal seats in Queensland and Western Sydney, but Victoria is also home to some key marginals, particularly in Melbourne’s east.

If the Victorian division can’t find the funds to replace its lamented Cormack dollars, the Turnbull government will be pretty much done for. With a one-seat majority, it can’t afford to sit on its hands in a state with eight marginal seats. The Cormack board is apparently considering sending funds to the federal office of the Liberals, bypassing Kroger and the state division, but whether this can compensate for a breakdown in the state organisation is an open question.

And that’s just the next electoral cycle. Longer term, the financial malaise within the Victorian Liberals could have profound implications for the whole country. Victorians make up 20 per cent of the current Liberal party room in Canberra. They also contribute more than their fair share to the ministry, holding 28 per cent of the Liberals’ places. Both the speaker of the House and the president of the Senate are Victorian Liberals. In other words, Liberals from the Garden State make a major contribution to the governance of the nation. If their organisational wing goes broke and can’t campaign properly, it will be felt at the highest levels.

The financial crisis in Victoria may not simply cause electoral underperformance. It could act as a catalyst for a more profound political change, too. For decades, the Liberal Party in Victoria has been undergoing a major cultural shift, transitioning in fits and starts from a moderate, liberal, pragmatic party to a more ideological, aggressively conservative, anti-establishment one.

As argued previously on these pages, they are essentially going feral, having spent so many years out of power in recent decades. The growing insurgency against the more moderate establishment in the party has been recruiting members, mounting preselection challenges and seizing positions on key organisational committees. It’s easy to imagine a scenario in which these forces seize the opportunity of a financial meltdown or electoral wipeout to mount a wider push for control.

Preselection challenges against sitting MPs are already being openly discussed. If that Victorian 20 per cent of federal Liberal MPs becomes markedly more conservative, the national factional balance could tip, changing the kinds of policies and issues the Liberals pursue and shifting the political centre of gravity. We’ve seen this kind of thing in the United States with the Tea Party, and again in US primaries this month, as Trumpian outsiders replace establishment figures, with drastic effects on the content and quality of political debate in that country. The lesson there is that small revolts in big parties can have disproportionately large impacts on the functioning of a political system.

So the crisis in Victoria’s Liberal Party is worth watching. For better or worse, the kind of politics we have in this country is deeply dependent on the state of our major political parties. If a big state division of one of those parties goes belly-up or dramatically changes character, it will have big implications for the country. Those on the left cheering the Liberal Party’s woes beware: its implosion may not mean that progressivism will come out on top on Spring Street or in Canberra. Instead, it may just poison political debate as a whole and bring about a state of political chaos unknown in this country since the early days of the party system.

You don’t need to like the Liberal Party to acknowledge that, as an institution for aggregating and organising diverse interests, it might make the political system a little more predictable, a little more reasonable, a little more functional. Perhaps it is just a bit too big to fail. ●