With the Commonwealth electoral roll in its best shape ever, are the Coalition’s worst fears being realised? Back in 2011–12, when the Gillard government was preparing to introduce direct enrolment, the Coalition was ferociously opposed. Direct enrolment would allow the Australian Electoral Commission to update people’s details, and add new voters, using data from other government agencies. At the time, it couldn’t do either without a signed form from the voter; it was only allowed to use that data to take people off the roll — if they moved house, for example, as millions do every year.

The Liberal Party — and shadow special minister of state Bronwyn Bishop in particular — screamed blue murder, claiming direct enrolment would facilitate voter fraud. The argument never made any sense because automation works against attempts to manipulate the roll. In reality, the Coalition was opposed for the same reason Labor and the Greens quite liked the idea: voters who fall off the roll, or don’t get onto it, tend to lean to the left. The most obvious examples are young people, renters, students and those who move around a lot.

Regardless of Senator Bishop and her colleagues, the legislation passed in 2012 and direct enrolment cranked into operation.

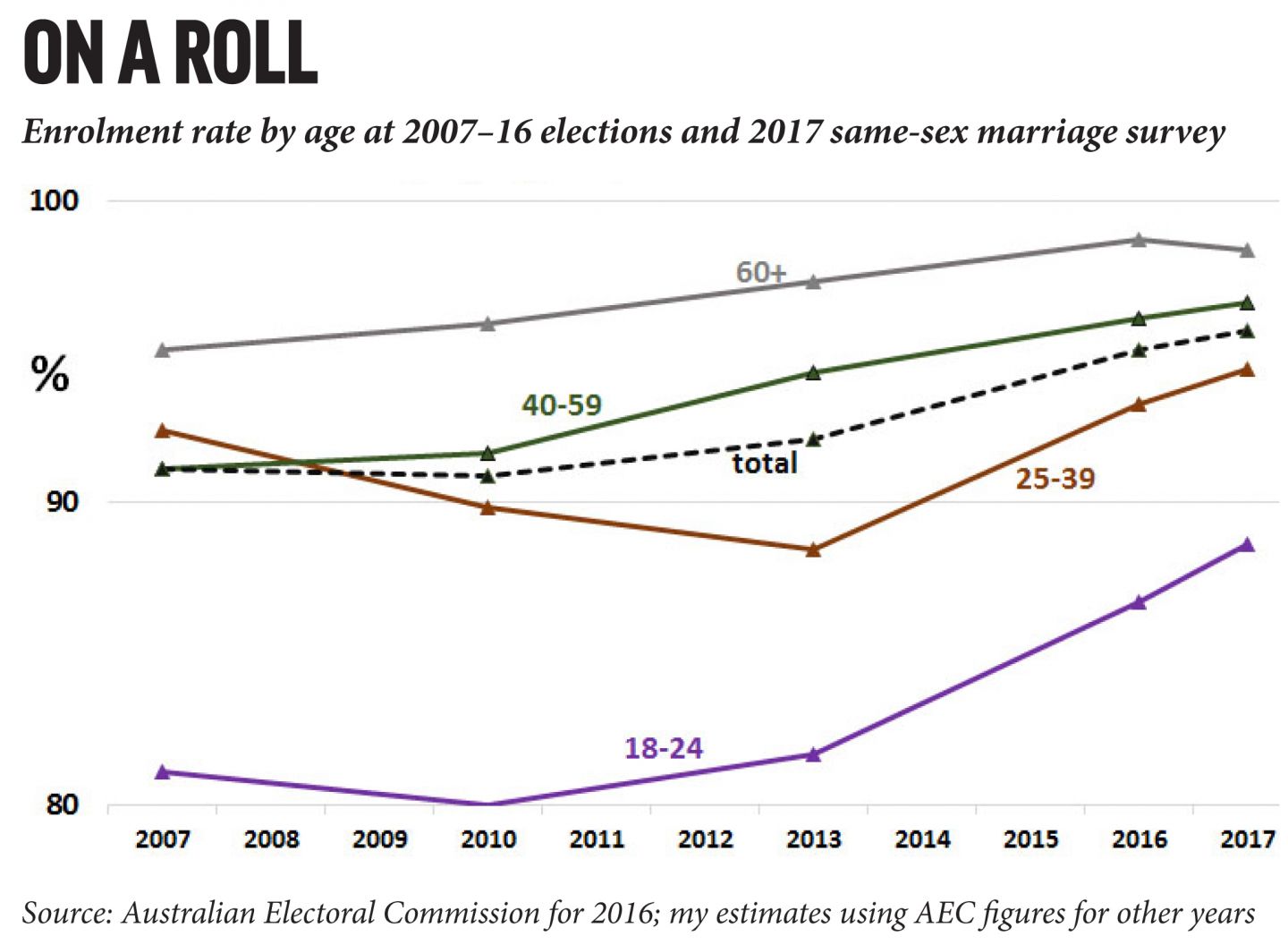

And so, at the 2016 federal election four years later, the AEC could boast about the most comprehensive roll ever, or at least on record (no one has done the numbers for all elections back to 1901), at 95.1 per cent of estimated eligible population. This was up from 92.4 per cent at the 2013 elections and 90.9 per cent in 2010.

(That’s eligible people in Australia. Another million or so Australians abroad aren’t included in the total possible number, although the less than 100,000 of them who are on the roll are included. Yes, the calculations are a bit messy.)

The biggest improvement was among the young: some 86.7 per cent of eligibles were now on the roll, up from (my estimate of) 80 per cent at the 2010 election.

This week brought more news about enrolments. The AEC released “close of roll” figures for the Australian Bureau of Statistics’s same-sex marriage survey, and while they didn’t include eligibles, a back-of-napkin guesstimate produces a new record: 95.7 per cent comprehensiveness, with an 88.6 per cent eighteen-to-twenty-four component.

The AEC has released several sets of estimated roll completeness by age group in recent years, but only once for an election — in 2016. But polling day is when the quality of the roll really matters, and for this reason I have estimated, by projecting the AEC’s eligible numbers backwards, the participation rate at recent elections. These are the figures going back to 2007:

The most dramatic component of the graph is the meteoric rise of youngsters. Less expected is the dip in the next age group, twenty-five to thirty-nine, in 2010 and again 2013; possibly these were most affected by the previous one-sided use of government agency data described above.

So does a comprehensive electoral roll really spell doom and gloom for the Coalition? No. Claims that the missing voters would lean 60–40 to Labor were far-fetched: voters under twenty-five might be overrepresented among the unenrolled, but they are a minority of them. And despite the lift in enrolments, the ageing of the population means eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds account for a smaller proportion of the roll (10.6 per cent) than in 2007 (11.3 per cent). Meanwhile, the seventy-plus group has grown from 13.2 to 15.1 per cent.

There’s also the fact that last year’s record participation rate was accompanied by another quite dramatic development: the lowest “turnout” figure since the introduction of compulsory voting in 1924. Turnout as a proportion of a very healthy total roll dropped substantially, although as a percentage of eligible Australians it increased a little. A big chunk of those newly enrolled voters hadn’t bothered to vote. And as the AEC continues burrowing deeper into the remaining hard-to-get group, we can expect this pattern to continue.

In other words, as more and more people are dragged onto the list, often without their knowledge (the AEC sends them letters informing them of their enrolment, but who reads those?) we can expect fewer and fewer of them to participate on polling day.

And here’s another thing: it is believed that tens of thousands of Australians enrolled last month specifically so they could participate in the ABS survey. What proportion will vote at the next general election and future ones? How many are in for a rude shock in the form of a “please explain” letter from the commission, followed by a fine?

Once you’re on the roll it’s difficult to get off.

As the list improves, the number of people chased up for not voting grows exponentially. That’s a problem not just for the individuals concerned, but also for government authorities and the public purse. The solution, as I argued last year, is to eliminate the fines — that is, make voting voluntary. But that’s another topic. •