Australia was once widely regarded as a nation that “punched above its weight” in international affairs. It’s a cliché, and not necessarily a helpful one, but it reflected a reputation gained over many years for constructive and influential diplomacy on many issues of global and regional significance. In one notable example, successive Australian governments – both Labor and Liberal–National – have played a leading role for more than thirty years in nuclear non-proliferation and arms control efforts. In the face of intransigence by the major powers (all of which had nuclear weapons), Australia applied its resources creatively and skilfully to achieve tangible benefits in the realm of peace and security.

Compare that with Australia’s approach to climate change – another issue of global importance where major power intransigence has long been contrary to Australia’s, and the world’s, long-term interests. After a decade of near total inaction under the Howard government, there were at least some improvements under Rudd-Gillard. With the expansion of the Renewable Energy Target and then, under Gillard, the creation of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and a modest de facto carbon tax (which would have become a weak emissions trading scheme with a very low price as of 1 July 2015), Australia took some significant steps in a more proactive direction to moderate Australia’s domestically-produced emissions.

But Australia’s “sphere of influence” over global emissions is not limited to the ones that it produces on home soil, and the collective emissions saved from the Rudd–Gillard government’s climate measures would have been more than wiped out by the massive expansion in coal and gas exports that it championed. This fossil fuel expansionism in the context of a rapidly dwindling “safe global budget” of “burnable carbon” ensured that Australia was still, all things considered, a global laggard. Moreover, Australia came nowhere near to fulfilling its potential in clean energy innovation, through which it could have played a global leadership role.

Things took a significant turn for the worse upon the ascendancy of the Abbott government. Repealing Australia’s extremely modest carbon price sent all the wrong signals to investors and to the rest of the world, as have the government’s (so far unsuccessful) attempts to abolish the other climate institutions created by the previous parliament. In substance, the Abbott government’s championing of coal and gas exports reflects a continuation of Labor policy. But rhetorically, the Abbott government’s coalphilia has reached new levels; its frankly bizarre fetishisation of coal (fast forward to the 1.15 minute mark) surpasses even that of Martin Ferguson, Labor’s fossil-friendly former energy and resources minister.

Moreover, the Abbott government has elevated the promotion of coal and the obstruction of climate initiatives to a foreign policy objective. It joined with Canada, another fossil fuel laggard, in an alliance to promote fossil fuels globally, prompting jibes about an “axis of carbon.” (Naively thinking that conservatives everywhere don’t care about conserving a liveable climate, they asked the conservative British and New Zealand governments to join the new dark force, and were promptly and publicly rebuffed.)

It has also waged a campaign against the UN Green Climate Fund, which is intended to facilitate financial flows from rich to poorer countries for reducing emissions and adapting to climate change. The amounts being discussed for the Fund are modest, and the Fund itself is a limited institution that represents a small fraction of the public and private financial flows needed to tackle climate change. But developing countries, understandably aggrieved at rich countries’ historical failure to act on climate change, see the latter’s contributions to the Fund as a litmus test of good faith in tackling climate change cooperatively. Suffice it to say, Abbott’s Australia flunked it.

International cooperative sentiment on climate change tends to go in waves, and a new wave has been swelling as countries prepare to announce their emissions reduction contributions (and, in the case of developed countries, also their pledges of financial support to the above-mentioned Fund) towards a multilateral climate agreement slated to be concluded in Paris in late 2015. Much of this has occurred beneath the surface, through concerted diplomatic initiatives over the last year or so – for example, in US–China bilateral climate talks, in the European Union’s internal debates over regional emissions objectives, and within the international financial institutions and various organs of the United Nations. In the context of this marked uptick in global climate diplomacy, Australia’s newfound obstructionism has earned it a reputation not merely as a laggard, but as a climate change pariah – an outcast perceived by others as destructive of accepted standards of international conduct.

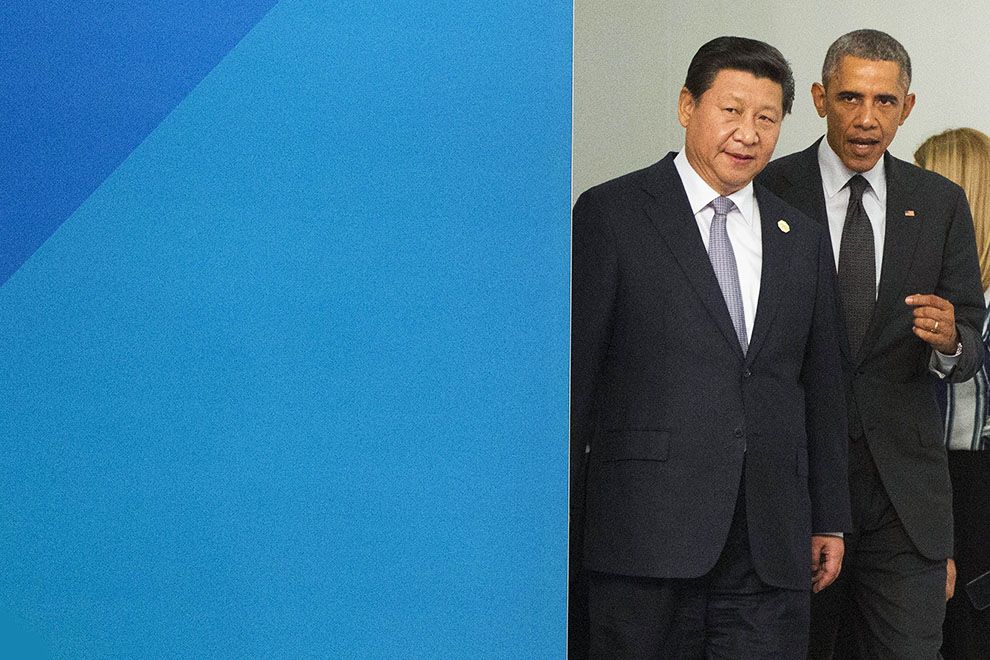

Last week, when this swelling wave of behind-the-scenes climate diplomacy spilled over into the public spotlight, Australia managed to downgrade its climate-response status further still: from pariah to embarrassment. A major public announcement on emissions reduction cooperation between the United States and China was followed by a concerted push from the most powerful members of the G20 to refocus that meeting on climate change, against the Abbott government’s determined wishes and efforts. The embarrassment to Australia was amplified by Tony Abbott’s churlish speech to G20 leaders, when he crowed about having abolished the carbon tax and built more roads, and bemoaned his government’s inability to legislate GP co-payments and slash funding for higher education.

Treasurer Joe Hockey argued that the G20 should be focused on “growth” not climate change. Even if we accept, for argument’s sake, Hockey’s premise that “growth” is the only international issue that the world’s most powerful nations should be discussing, the implication that action on climate change is a barrier to growth deserves careful scrutiny. It is at best recklessly simplistic and at worst a downright falsehood. It has long been accepted that large-scale reductions in global emissions are essential to minimising risks to growth and prosperity over the long term from the potentially catastrophic impacts of climate change. But recent research and policy analysis by some of the world’s leading economic thinkers and institutions has focused on the potentially immense contribution a well-designed climate policy can make to a country’s economic growth in the medium term (by which I mean, roughly, the next three to fifteen years), because of the economic effects such policies can have in addition to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

First, climate policy can improve the productivity of energy and natural resource use by mandating or incentivising the use of more energy-efficient buildings, vehicles and appliances, for example. Second, whereas muddled climate policies and mixed messages raise the risk of investing in infrastructure, particularly in the energy sector, well-designed climate policy can reduce this “policy risk” and induce private investment in clean infrastructure such as renewable electricity generation, stimulating growth. Third, climate policies in the land sector can improve the “ecosystem services” provided by soils, forests, rivers and so on, with growth-enhancing benefits for agriculture and other environmentally sensitive sectors.

And fourth, climate policies, if well-designed and targeted, can induce innovation in low/zero-carbon and environmental industries. One medium-term effect of such policies on growth is in the fostering of lower relative prices for low/zero-carbon substitutes over time, generating cost savings over the medium- to long-term relative to costlier, high-carbon kit. Think, for example, of the low costs of wind and solar energy we enjoy in Australia today, thanks largely to early targeted support for innovation in these technologies in Europe and China when costs were initially high.

Another important growth effect of green innovation is less obvious, but is likely to be even more important than the first: there are good theoretical reasons, supported by a growing body of empirical evidence, to conclude that innovation in green technologies leads to a significant “spillover” of new ideas and knowledge into other sectors. Much higher than those for dirty, incumbent technologies, this spillover begets further innovation and growth in other sectors. With well-targeted policy and institutional change, the potential for innovation-led growth in the transition to a zero carbon economy is immense – likely to be in the order of a “new energy-industrial revolution” or a new “golden age” of capitalism.

The effect that good climate policies can have on growth in the short term is more complicated, and depends partly on both the structure of the economy in question and the cyclical conditions there. Low-carbon structural change is likely to be net beneficial to most countries in the medium term for the reasons discussed above, but the transition will involve some absolute costs in the short term as capital and labour are reallocated away from higher carbon sectors and into lower-carbon ones. Other things being equal, the short-term costs of structural transition will be higher (though not necessarily prohibitively so) in those countries with a relatively high proportion of the economy in high carbon sectors, and in those countries where unemployment is low and interest rates are high (making new, debt-financed investments in green infrastructure more expensive). By contrast, in those countries and regions, like much of Europe, where interest rates are very low and there is high unemployment, climate action can be a stimulus to growth in the short term: governments can borrow money at low interest to invest in new green infrastructure, crowding in private capital and creating new jobs.

This more nuanced understanding of the relationship between climate change and growth across different timescales and different macroeconomic conditions reveals that climate change is, in fact, an ideal category for international cooperation among the G20, even on Hockey’s narrow interpretation of that institution’s role. Indeed, international climate cooperation is, in its structure and in its relationship to economic growth, more akin to cooperation on trade liberalisation – a perennial priority among the G20 – than the inappropriate “tragedy of the commons” model that Joe Hockey seems to have in mind. (Freer trade tends to increase global and national growth in the medium term, meaning countries have both altruistic and self-interested incentives to cooperate, yet it often involves absolute costs and adjustments in the short term for previously protected industries, which raises legitimate distributional questions and makes the short-term politics challenging.)

Better coordination of fiscal reforms – such as through the introduction of carbon taxes and local pollution taxes, the removal of subsidies for fossil fuels, and strengthened public support for innovation (for researching, developing, demonstrating and deploying zero carbon technologies) – would have been an obvious focus for a medium-term-growth-oriented G20. Coordination among the G20 on such policies and measures would inevitably increase their short- and medium-term benefits, and reduce their costs, compared with unilateral action. These days, nothing on this list of policy suggestions is at the cutting edge of radical green thought; it reads more like a standard prescription for green growth from the World Bank, the OECD and the IMF.

Of course, we should also question Hockey’s narrow focus on growth. This is not the place to enter important debates about theories of value and indicators of national progress, but we can be certain that most governments are, or at least ought to be, concerned ultimately about things other than the mere quantity of GDP growth. Many are also rightly concerned, to put it one way, about the “quality” of growth. Aside from boosting medium-term (and in some cases, short-term) growth, there are many “co-benefits” of well-designed climate policies that improve the quality of people’s lives. More compact cities with green spaces and efficient public transport, walking and cycling infrastructure are not only more economically productive; the reduced local pollution, congestion, noise and waste also makes them more appealing places to live. A flourishing natural environment, and more localised and secure energy sources, are all desirable socioeconomic developments for reasons that go well beyond their effects on growth.

The distinction between, and relationship between, growth and standards of living is not just a “first world problem”; it is a matter of real and lively debate in many parts of the developing world. Many people are questioning the wisdom of the “grow rich first, clean up later” pattern of development to which the Abbott government seems to think all people in poor or middle-income countries aspire. I’m writing this piece from Beijing, where the level of PM2.5 particulate air pollution just reached a staggering 583 on the US EPA’s Air Quality Index (above 300 is considered “hazardous” to human health, and this is the highest category). It is incidents like these (the index often exceeds 500 in Beijing and other cities in China, as it does in many other cities around the world) that have prompted senior Chinese officials, not to mention ordinary citizens, to ask themselves: “what is the point of growth if our cities are unliveable?”

Hazardous urban air pollution – most of which is caused by burning coal, and much of the remainder by vehicles – is one reason among many why China is aiming to restructure its economy away from heavy, energy-intensive industries and fossil fuels and towards a more resource-efficient, environmentally sustainable, equitable and low-carbon model of development. Other reasons include economic productivity, energy security, water stress, and market opportunities in the green economy. China has already undertaken major initiatives to conserve energy, close old and inefficient power stations and industrial plants, cap and reduce coal use, deploy non-fossil energy sources through massive investments in renewable energy, and experiment with carbon pricing. Deeper efforts along these lines would yield great benefits for China and for the world.

Importantly, China’s new development model represents a major shift from the 2000–11 period of heavy industrialisation-driven growth, a strategic change of policy that China has determined to be in its own national interests. It is this shift that has enabled the historic turnaround in China’s attitude to cooperation on climate change, heralded publicly last week when President Xi committed China to a peaking year for emissions of around 2030 (widely regarded as a conservative estimate that is likely to be bettered in practice). The president also announced a target for meeting 20 per cent of China’s primary energy demand from non-fossil sources by 2030, which will require an additional 800–1000 gigawatts of non-fossil energy capacity to be deployed by that time – an immense undertaking, equivalent to almost the total current electricity generation capacity in the United States.

This should not be dismissed as mere “non-binding” symbolism, as Abbott government ministers were at pains to imply last week. We can be confident in the sincerity of China’s ambition to meet, and arguably to better, these goals because they are a product of China’s self-determined development path. Moreover, these targets will be incorporated into China’s development planning system and translated into specific laws, policies and investments, which is a much stronger indicator of their credibility than whether the targets are “legally binding” under international law.

The most important challenges China faces are, rather, in the implementation of the policies and measures needed to achieve these goals. How effectively can central policy be translated into provincial and municipal action? Can vested interests be overcome? How can the interactions between many different policies be managed effectively? How can the structural transition from brown to green be managed effectively in the short term? How can the quality of relevant data be improved? Can clean infrastructure financing be scaled up even further? Can China’s capacity for indigenous technological innovation be expanded relatively quickly? These and other challenges are real and significant, and go to the heart of China’s development prospects in the coming two decades. But they are not challenges of strategic intention or sincerity.

The question that every nation – not least Australia – should be asking itself with regard to China’s new climate targets and development plans is, therefore, not “is this meaningful?” but rather “how can we help?” Australia is engaged in some practical cooperative efforts with China on low-carbon and environmental technology and processes, and this cooperation was expanded at the G20 last week with a modest bilateral initiative to support energy efficiency and environmental reporting. But this is peanuts compared with the size of the task China faces.

As a rich nation with abundant and cheap renewable energy resources, world-class capabilities in science, technology and professional services (including environmental and climate-related services), and faced with catastrophic risks from unchecked global warming, Australia has a grave responsibility to play a major role in the transition to a decarbonised China, and a decarbonised world. It is precisely the area where Australia should be punching above its weight – or at least in its own (hefty) weight class. The G20 was not only a major missed opportunity to do so, but also an embarrassing demonstration of the Abbott government’s destructive and recalcitrant agenda.

On climate change, the only punches Australia is landing are on itself. •