As anyone who has been paying attention is aware, the emerging tensions between China and the United States have created a dilemma for Australia. Key elements of those tensions include ongoing friction over both countries’ trade; China’s posture in the South China Sea; and the ever-present problem arising from US military protection of Taiwan, over which neither we nor the United States challenge China’s claim of sovereignty.

In a nutshell, our dilemma arises from the fact that we have relied on the United States for our security since the fall of Singapore in 1942, but in recent decades China has become by far our largest trading partner. China represents a quarter of our two-way trade, taking about a third of our exports and providing about a fifth of our imports.

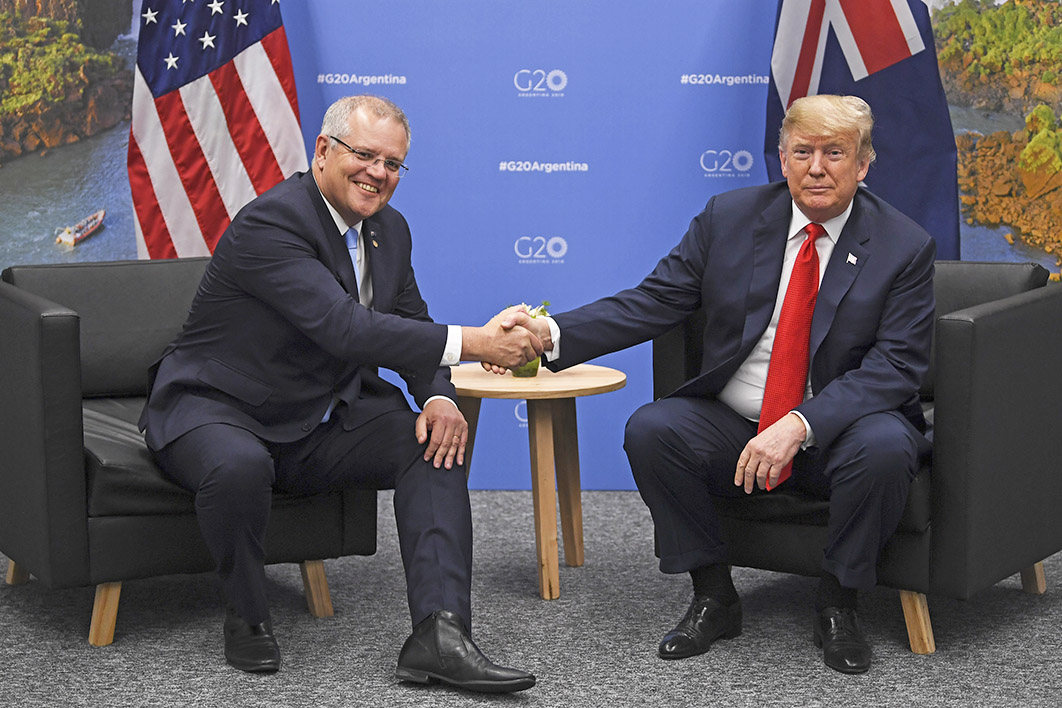

John Howard was able to assert with some plausibility that we didn’t have to choose between our ally and our major trading partner, but in the age of Xi Jinping and Donald Trump that assuredly doesn’t apply. Beijing and Washington are becoming increasingly assertive and increasingly strategically competitive. Plausible scenarios in both the military/strategic and trade domains will force us to make choices, and we need to think carefully, ahead of time, about how we would handle as wide a variety of scenarios as we can imagine. This level of forethought will enable us to respond in a timely and appropriate way to such exigencies as do arise and, just as importantly, to signal to each of these great powers both what we expect of them and what they can expect of us.

Our allies and those with whom we have more difficult relations can cope with our taking different positions from them, as long as we are up-front and consistent. The United States coped with Britain’s decision not to go into Vietnam and Canada’s decision not to participate in the invasion of Iraq. What friends and antagonists most dislike are surprises.

Navigating this tricky environment is going to require careful thought and full national debate about where Australia’s interests lie. These are matters on which reasonable people can differ, but the debate must be held in good faith and without political point-scoring. Only if we have a clear and widely agreed picture of our national interest can we decide and communicate what we will and won’t do.

A good place to start is the trade war being waged by the United States, both because we have a history of active multilateral trade diplomacy going back to the signature of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, in 1947, and because it is an opportunity to demonstrate to China that we are not an automatic and uncritical supporter of the United States. While China’s trade policies are not beyond reproach, if our decades of trade diplomacy mean anything, they mean that we stand for the maximum liberalisation of international trade and investment, and we should be saying loudly and clearly that we do not support the US policy of unilaterally imposing or raising tariffs.

It is also a good place to start because it is in a non-military realm and therefore less bound up in the emerging power play between the dominant United States and the emergent China. Relatively speaking, it is an everyday item of business.

Next, on the boundary between economic and military action, we have a right — indeed a duty — to object to Donald Trump’s proclivity to impose unilateral sanctions and then demand that allies follow. Sanctions are a hostile act, tantamount to an act of war. In medieval times they were called sieges, and no one was in any doubt that they were an instrument of war.

In the military realm, we desperately need to abandon decades of lazy thought and undertake a realistic analysis of our obligations and expectations under the ANZUS treaty, which has been invoked by politicians of both parties as the foundation of our security since its inception in 1951. ANZUS is not, in fact, a strong treaty. The obligations it contains are limited and weak because an unenthusiastic United States wanted it that way. All it requires of the parties is that, in the event of a threat in the Pacific to the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the parties, those parties will consult, and in the event of an armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the parties, they will act to meet the common danger in accordance with their own constitutional processes.

So let’s be clear about ANZUS: the United States is only obliged to do anything for Australia in response to an armed attack on us or one of our island territories, and all it is required to do is act to meet the common danger through its own constitutional processes — which locate the war-making power in the Congress, not the president. Hardly a bankable guarantee of our security.

In practice, any US interest in Australia’s security stems more from the close relationship between our respective armed forces, the very close intelligence and technical relationships, the joint facilities in Australia, and the very high levels of US investment here. Those clear US interests, as distinct from the words written on a piece of paper in 1951, will ensure a certain level of US tolerance for Australia taking different positions on issues where we perceive our interests to differ.

As part of any consideration of the security relationship with the United States we need to undertake an audit of all joint facilities in Australia, and the US use of them and of Australian facilities, and consider whether they make us safer or simply turn us into a target.

In relation to China, we need to decide exactly where our interests lie in the South China Sea. Clearly they lie in the direction of freedom of navigation and a rules-based order derived strictly from the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS. On this basis, we can decline US invitations to participate in joint freedom-of-navigation operations, but argue strictly from UNCLOS principles that, as a party to the convention, China must abandon historical claims based on the “nine-dash line.” Legally, any historical rights China may have had to the resources of the South China Sea were extinguished to the extent that they were incompatible with the exclusive economic zones established by the convention. These principles gives us a basis to argue for better Chinese behaviour in the South China Sea without getting involved in the Washington–Beijing power struggle.

Of one thing we may be sure: after its “century of humiliation” China is in no mood to be pushed around by anyone. Quiet, independent diplomacy behind closed doors will stand us in far better stead than the muscle-flexing and megaphone diplomacy currently favoured by the United States and a gaggle of the usual suspects.

The elephant in the room is, of course, Taiwan. Defence writers of the eminence of Paul Dibb and Hugh White have argued that Australia’s alliance with America would be fatally undermined if we did not join the United States in the defence of Taiwan in the event of a Chinese attack, and over the years various Republican figures have been gung-ho about what would be expected of Australia in this eventuality. Dibb argues that an attack on Taiwan “certainly comes within the ANZUS Treaty’s definition of an armed attack in ‘the Pacific Area.’” I disagree with that view of what ANZUS requires, if not about the politics: the complete phrase is “an armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the Parties,” and Taiwan is not a party to ANZUS.

Like me, Hugh White argues that the requirement to defend Taiwan is not evident in the text of the treaty itself. White cites the foremost legal authority on the matter, J.G. Starke, who writes that the context of Article 4 makes clear that the “Pacific Area” doesn’t include Taiwan, because Australia didn’t want it to.

I think our best approach is to cut the defence of Taiwan unambiguously out of the picture, arguing that we expect the grown-ups in Beijing, Taipei and Washington to maintain the peace, and not to assume that Australian forces would be made available in the event of their failure to do so. Having acknowledged Beijing’s claim that Taiwan is a province of China, and having recognised that Taipei, like Beijing, regards itself as the legitimate government of an undivided China, why would we allow ourselves to become involved militarily in a confrontation to which we cannot make a meaningful difference?

All of these issues will require careful thought and diligent and skilful diplomacy. The point is that Australia, with its long history of effective diplomacy, is up to the task of navigating our way through the challenges of the US–China confrontations provided we pay careful regard to our national interests, and act as an independent state on the basis of the applicable rules.

And just to make sure we do not let our proclivity towards military action get the better of us, we should follow the US lead and locate the power to decide whether we go to war in parliament and not executive government. •