Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin: The Making of the Modern Labor Party

By Liam Byrne | Melbourne University Press | $34.99 | 187 pages

In the pantheon of Labor Party heroes, John Curtin and James Scullin loom large, but for very different reasons. Scullin is seen as a tragic victim of the Great Depression, a valiant trier brought down by hostile forces inside his own party and beyond. Curtin, the most revered of all, is remembered for his unstinting leadership of a fearful nation during the darkest days of the second world war.

Yet, as Liam Byrne reminds us in this remarkable book, both men risk being overshadowed by their contrasting fates as prime minister. Byrne, the ACTU historian, argues that there is much more to each of their stories. Scullin is too easily dismissed as a tragic and ill-fated figure overwhelmed by circumstance; Curtin risks sanctification, his stoic leadership “obscuring the real man who bore the nation’s burdens and suffered the cost.”

Recounted here are events that took place in the early twentieth century, long before each man became prime minister. Byrne details their long and often arduous experience in Labor politics, noting how each in his own way came to influence the growing party at a time when it was alive to the spark of new ideas. Each was from Irish immigrant stock, an outsider in an Anglo-dominated world, who found an intellectual and spiritual home, not to mention camaraderie, in the party.

It was a time of intense political ferment, and the radical Curtin and the moderate Scullin frequently found themselves on the opposite sides of the debate about what Labor stood for. Was it seeking to reform the capitalist system from within or radically restructure society along socialist lines?

With an exquisite eye for detail, Byrne recounts how both men became intellectuals and powerbrokers in the wider labour movement, addressing meetings, writing articles, arguing, persuading, cajoling and, above all, leading. Interestingly, Scullin, the former timber-cutter and grocer, and Curtin, the former factory estimator and union official, both became influential newspaper editors — the former at the Evening Echo, a Ballarat-based Labor daily whose readership extended far beyond that town, the latter at the Timber Worker and the Westralian Worker. Curtin revelled in his role at both papers, carefully dissecting the issues of the day and keenly focused on both educating and raising the consciousness of the working class.

Scullin’s and Curtin’s lives and lived experiences were deeply entwined with the emerging industrial and political wings of the movement as they grappled with the complexities of capitalism, which makes this is as much a history of the nascent Labor Party as it is a study of two of its luminaries. An illuminating quotation from Curtin about his time as an estimator at the Titan Manufacturing Company shows how work, often tedious, repetitive and poorly remunerated, shaped his worldview: hour after hour, day after day, “I calculated, measured and otherwise evolved the precise cost to a gentleman profiteer of importing wire from Germany.” Did it have to be like this? Curtin set out to educate himself, devouring books, haunting public libraries.

Sport also figured large in his life, and his sporting connections led him to socialise with men involved in politics, bringing him into the circle of Frank Anstey and later the British union leader Tom Mann, whose time in Australia had a marked impact on the labour movement.

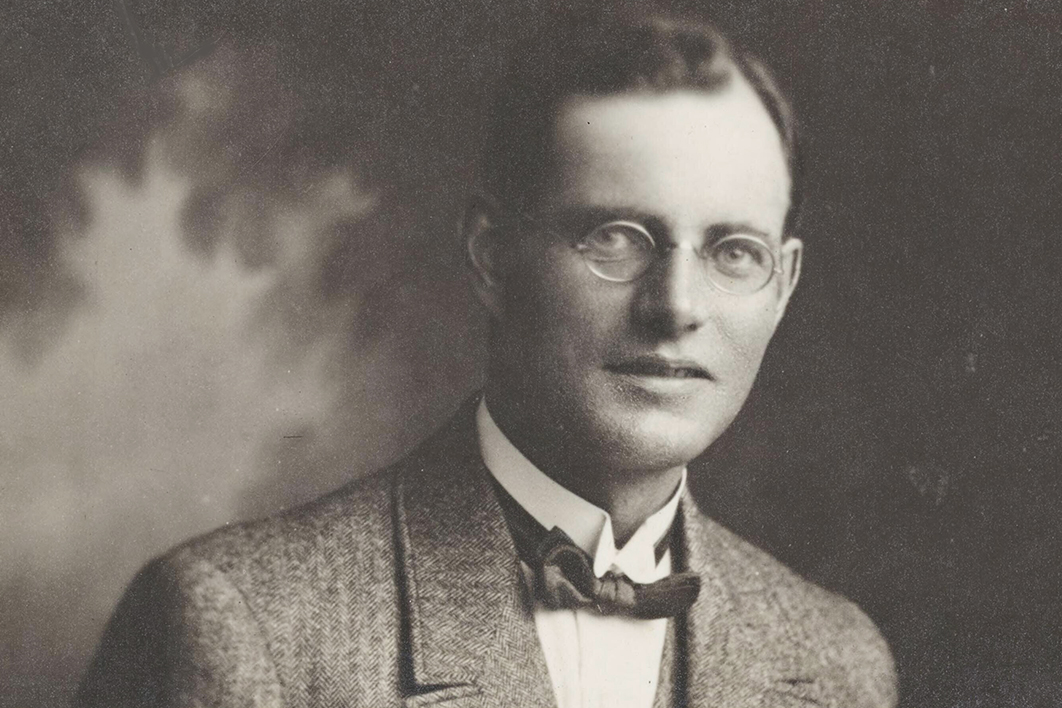

More than a victim: James Scullin in the 1920s. Detail from a photo by Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Falk/National Library of Australia

Scullin, who excelled as a debater, had been selected in 1906 to run for Labor against prime minister Alfred Deakin. While he failed to win the seat, his performance attracted notice, drawing him into the circle of the influential Australian Workers Union powerbroker, Ted Grayndler, a pragmatist sceptical of socialist dreams. He became a political organiser for the Australian Workers Union, travelling through country Victoria to spread the message and draw recruits.

The Great War was a testing time for Labor, which split for the first time when Billy Hughes and his followers defected over conscription. Scullin, a devout Catholic, supported the war effort — albeit, as Byrne notes, with stoicism rather than enthusiasm. He was in favour of compulsory military training, and addressed a Victorian Labor conference on the issue. Curtin was an ardent anti-conscriptionist.

Discontent over the cost of living erupted after the war, resulting in widespread industrial action. The Labor moderates struggled to retain control of the party, in 1919 adopting a Victorian motion for “the democratic control of all agencies of production, distribution, and exchange.” Fearing a rising radical tide, Scullin and his colleagues decided on a rhetorical shift, embracing the concept of socialist change, but all the while emphasising that such a transformation belonged not to the present but the distant future.

Events far away were beginning to add spice to this already volatile mix. The rise and apparent success of the Bolsheviks in Russia emboldened elements of the far left, and a number of small socialist groups formed the first Communist Party of Australia. Issues came to a head at the All Australian Trades Union Conference in Melbourne in 1921. From the chair, Melbourne Trades Hall Council secretary Jack Holloway referred to “lightning changes all over the world” and the view that, to some at least, the gradualist program of the Labor Party was already becoming obsolete.

This was perhaps the most crucial gathering yet of political labour, and Scullin and Curtin were key players. Scullin was among the moderates gathered around the AWU, while Curtin lined up with the parliamentary socialists associated with the Victorian Socialist Party. Further to the left were the International Workers of the World–inspired group advocating One Big Union, founding Communist Party member Jock Garden, and a delegation known as the Trades Hall Reds.

Fiery debate and endless procedural distractions ensued, but the eventual compromise was an agreement that the party would pursue “the socialisation of industry, production, distribution, and exchange.” Scullin and Curtin were both elected to the committee to oversee its incorporation into the party platform.

At the subsequent Labor national conference in Brisbane (which Curtin could not attend due to illness), the “socialist objective” was again heatedly debated, with arguing it was abstract to the point of meaninglessness. Labor was “being prostituted by communists,” said Queensland premier “Red Ted” Theodore, moving an amendment to the effect that “nationalisation” would apply only to industries “which are used under capitalism to despoil the community.” Scullin led the opposition and the amendment was defeated. Labor got its socialist objective, democratic socialisation, but it was not quite (as radical) as the socialists wanted. Scullin’s moderates carried the day.

In a final chapter, Byrne offers a thoughtful critique of the present-day party, lamenting the absence of the kind of working-class intellectual that Scullin and Curtin represented. “No more does Labor draw upon leaders with direct experience of working-class life,” he writes, and much has thus been lost of its rich tradition:

Labor has lost the capacity to host alternative worldviews of commitment to social change within the structures of the party. It has ceased to be a site of intellectual creation, where ideological contest — expressed through articles and pamphlets, but also motions at conferences, arguments in branches and other traditional forms of power distribution and meaning-creation — generates ideas and forces up-and-coming leaders to defend their perspective and hone their persuasive capabilities.

In short, it has ceased to be a party of ideas; it no longer articulates a vision of what might be. Byrne argues that while the socialist tradition is now merely historic, and that the prevailing moderate tradition, devoid of its historic rival, has become enervated and incapable of devising new schemes for transformative change that would fundamentally alter Australia over the longer term.

While the objective (as vague as it is) has long been the subject of controversy both within and outside the party, its symbolic importance cannot be overstated. It represents both a critique of prevailing conditions at the time it was conceived and the essence of a way forward, with a boldness and audacity that are no longer in evidence. But Labor was founded as a party of change and transformation, writes Byrne, and — as Curtin’s and Scullin’s careers attest — it can be so again.

This is an extraordinarily engaging book by a rising young historian. Liam Byrne brings the past to vibrant life in way that is both subject-focused and intellectually cogent, vividly depicting a lost world of ideas, debate, vision and leaders who fought tenaciously for a better world, no matter how hard the road. And Scullin and Curtin are mercifully rescued from caricature. •