When Malcolm Fraser’s lower lip momentarily quivered on election night 1983, it sent millions of Australians whooping. The villain of 1975, that great divider of Australian society, had been vanquished.

But it was soon apparent, if it hadn’t been already, that the new regime would be nothing like Gough Whitlam’s. For the true believers, and politics watchers in general, Bob Hawke’s Labor government was, for the first few years at least, boring: timid, conservative, Liberal-lite, terrified of rocking the boat.

Wasn’t it the party’s lot in life to get elected, do great stuff and then go down in a blaze of glory?

The Labor rusted-ons had tended to prefer the policy-oriented Bill Hayden to the flamboyant but perhaps substance-deprived Hawke anyway.

But contrary to some expectations, Hawke turned out not to be a Reaganesque figurehead who left the thinking and action to others.

By 1984 the word “pragmatic” was being generously employed. Mostly with derision — isn’t this lot unadventurous? — but also with implied acceptance that if you actually want to leave a mark it wouldn’t hurt to stay in power for more than a few years.

And the government just got more and more “right wing,” more disappointing for membership. Core supporters’ strongest loathing was reserved for treasurer Paul Keating, always hobnobbing with banker types, wanting to do the sort of things the Liberals would do.

Labor stayed in power for thirteen years partly because, well, if you reckon it was bad, the Liberals would be even worse. But also, during the balance-of-payments crisis from 1986, they were seen as the steady, safer, and now economically courageous alternative.

But many traditional Labor supporters did cross over and vote conservative, and Coalition supporters found themselves moving the other way. (The 1987 election in particular saw a re-alignment.) After Labor had lost office in 1996 it became apparent it had big problems with its membership.

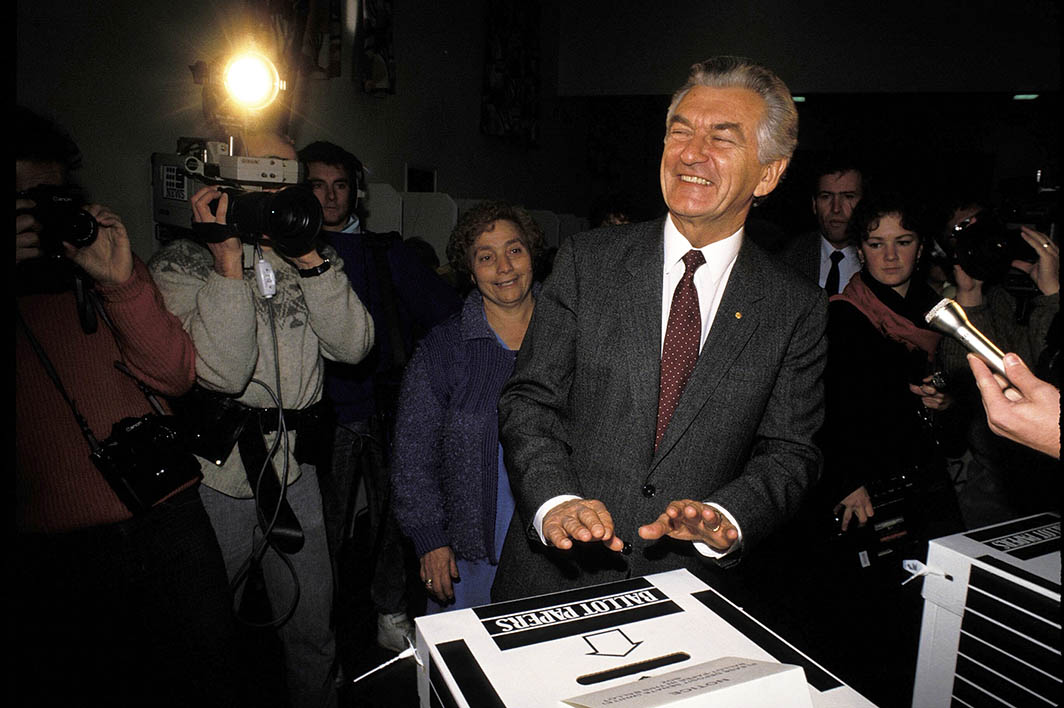

Hawke’s three re-elections were all pretty close. The first, in 1984, was a classic of the David and Goliath genre, where the popular incumbent gets a bloody nose from a supposedly deadbeat opponent. The prime minister’s huge popularity artificially inflated opinion poll voting-intention figures and election day became a relatively close-run thing. (Theresa May versus Jeremy Corbyn in 2017 is another in the category.)

In fact, a feature of Hawke Labor across those elections was that the prime minister’s approval ratings were high throughout each term yet government support went backwards in polling during election campaigns.

Back then Labor often lagged in primary support and led after preferences, but election watchers weren’t necessarily au fait with the concept of two-party-preferred. Newspoll didn’t even publish two-party-preferred figures until the 1993 campaign, and didn’t bother producing them outside campaigns until 2002.

At the 1987 election, for the first time, a national primary-vote lead was overturned after preferences (the second was in 2010). And it remains the only federal election at which a national swing to the opposition translated to a net seat gain for the government.

Then, of course, 1990 saw the Coalition win a slight majority of the two-party-preferred vote but come up short in seats.

The platform Hawke took to the 1983 election, mostly Hayden’s, was ambitious by modern standards, but his government’s re-elections mostly involved standing on its record and warning of the dire consequences of change. As governments routinely do today.

Treasurer Keating was particularly adept at scorning the Liberals for lacking the fortitude to make the difficult, macho decisions he had, then in the next breath conjuring up Armageddon should their mad economic prescriptions be let loose on the country.

The Coalition for its part assisted by offering up big juicy campaign manifestos, most famously in 1993 (when Keating was prime minister) but also in 1987. Here, for example, is John Howard’s shadow treasurer Jim Carlton in that earlier election:

What we are talking about is a complete change in the Australian economy. A complete change in the macroeconomic climate. Not minute arguments with economists about shadings. The real guts of the thing is getting the framework right, getting industrial relations right, getting tax right, getting the fundamentals right.

Brrrr.

Most of the reforms Hawke and Keating are celebrated for — floating the dollar, privatisation, tariff reduction, deregulation and so on — were not taken to elections first. These days, folklore has it that they patiently explained these to voters, convincing them of the need for change, but it’s truer to say they just did them, got them through the Senate with the support of either the Coalition or the Democrats, and then hoped that voters would get over it by the election. What’s done is done, and it’s tricky for oppositions to promise to undo policy.

So they gave up on land rights, sold uranium to the French, broke election promises, privatised, deregulated, introduced HECS and prioritised fiscal rectitude. Even Paul Keating’s beloved consumption tax looked a fait accompli for a while in 1985.

It was all life education for the true believers, who either were inch by inch dragged kicking and screaming into the pragmatic “economically rational” real world, or departed in disgust.

Today politicians and commentators blather incessantly about past greats, but Hawke and Keating were in no doubt that they themselves were the best thing since sliced bread, and certainly better than Whitlam, that practitioner of “the politics of the warm inner glow,” as Keating described him.

They were modern and forward- not backward-looking, but “progressive” didn’t come into it. It was a blokey affair. We knew at the time that the Hawke team were economic hardheads, but that social stuff wasn’t really contested. Fraser had not been particularly conservative that way. But Hawke’s retorts to attempts to capitalise on community discontent with Asian immigration, first by Andrew Peacock and then more overtly by John Howard, were unequivocal.

The response to the HIV epidemic was perceived as typically Australian, practical and no-nonsense, not hung up like in Britain and the United States. Australia was unideological and, if not progressive, then not reactionary either. If nothing else, we were too apathetic to get worked up about these things.

But Howard’s 1996 victory, in a drover’s dog election, changed the way Australian storytellers described our country. It turns out, they reckoned, that Australians are deeply conservative after all. Didn’t we keep electing Howard? None internalised this theme more than the Labor Party, who especially after 2001 obsessed about finding the messiah who would connect with socially conservative “battlers” as Howard did.

After the 2004 loss a certain self-promoting AWU leader called Bill Shorten directed such nagging at Mark Latham, of all people — the party had been too obsessed with trendy issues like Indigenous rights and refugees, not concerned with ordinary churchgoing Aussies.

This conviction of the deep conservativism of Australian people infected the politics of all Labor leaders — most of all, to the point of caricature, Julia Gillard.

Shorten today is a much-morphed figure, casting himself as a mixture of Hawke and Justin Trudeau. At time of writing he is not yet prime minister, however. •