The politics of statuary have been big news in Britain this year, beginning when a group of Oxford University students echoed their counterparts in South Africa by campaigning for the removal of a figure of Cecil Rhodes, the Victorian imperialist and (with his ill-gotten gains) well-known benefactor. A by-product of the proliferating disputes has been a rare focus on the warriors and statesmen who still dot Britain’s city squares and public parks.

Overwhelmingly male they may be, but surprisingly few of the memorialised are twentieth-century leaders. Leaving aside the special case of Westminster itself – Winston Churchill looms over Parliament Square, Margaret Thatcher is safely ensconced inside the Houses of Parliament complex – it would make a good quiz question: which prime ministers since 1900 are remembered in this way, and where? An unlikely collection is the answer, and it evidently has more to do with local enthusiasm than any official initiative. By serendipity, it also produces a neat political balance.

Lord Salisbury, an influential Conservative peer whose third term ended in 1902, guards the entrance to his family estate at Hatfield, north of London. Henry Campbell-Bannerman, a humane Scots Liberal, is on a leafy road in Stirling. Lloyd George, the mercurial “Welsh wizard” who gave Liberalism zing (and bonded with compatriot Billy Hughes during the Great War), stands proud both in his Caernarfon constituency and in Cardiff. Alec Douglas-Home, a Tory “countryman” who briefly occupied 10 Downing Street in the early 1960s, bides outside his own ancestral grounds in the Scottish borders.

Two Labour prime ministers complete the list. Clement Attlee stands modest at the approach to Queen Mary University in east London, near the site of the hall where he welcomed news of the party’s sweeping victory in 1945. And Harold Wilson, in office for eight years between 1964 and 1976, has two statues: one in his birthplace of Huddersfield, in west Yorkshire, the other in his constituency of Huyton, near Liverpool. Each was unveiled, in 1999 and 2006, by Tony Blair, who joins the two men in the trilogy of Labour leaders to have won a general election in the last seventy years.

Wilson’s distinction might be thought fitting, for he came out ahead in four of the five contests he fought, a record no twentieth-century rival of any party can match. (To emphasise the point, ten of the eleven British elections between 1964 and 2005 were won by Wilson, Thatcher or Blair.) Yet if Attlee is canonised by posterity and Blair execrated, and if Thatcher’s reputation mixes respect and loathing, Wilson has often seemed a marginal figure, overshadowed by the convulsive changes that succeeded his time in office.

Now, three landmark anniversaries – of his birth (11 March 1916), his most decisive victory (31 March 1966), and his surprise resignation (16 March 1976) – all but demand a retrospect. Fortuitously, the current political scene also has many Wilson-era echoes. A referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union on 23 June, four decades after the previous such vote, is the most resounding, with divisions over nuclear weapons and within the Labour Party close behind.

Another echo brings Wilson himself closer. The very definition of what it means to be a successful leader has been in flux since the arrival of television as a mass medium. Democratic jousts began to require a repertoire of visual and performative skills, to be displayed before a newly constituted audience in a variety of contexts (studio, filmed conference and hustings, encounters with voters). With the advice of sharp advisers such as David Kingsley and Denis Lyons, from the worlds of advertising and public relations, Wilson customised his TV slots for news clips, orchestrated confrontations with hecklers at public meetings to showcase his skills, and grasped the power of slogans (“Let’s go with Labour and we’ll get things done” in 1964, “You know Labour government works” in 1966).

By treating these techniques as an opportunity rather than a constraint, and in allying them to a coherent political message and image, Harold Wilson was a pioneer. Blair was astute as well as artful when, in unveiling that 2006 statue, he called Wilson “the first modern prime minister.”

“In British politics, where there is death there is hope.” The evergreen jest attributed to the Labour intellectual Harold Laski, who died in 1950, precisely captures Harold Wilson’s rise to the party leadership in February 1963 and Tony Blair’s in May 1994. In short: after long opposition and internal trauma, but with victory against a tired Conservative government at last in sight, Labour’s respected centre-right leader died suddenly, to be replaced by an energetic younger figure who went on to clinch the first of several victories.

Wilson’s chance came when the fates struck down Hugh Gaitskell, Labour leader since 1955. In the subsequent vote of Labour parliamentarians, the centre-left Wilson defeated the “Gaitskellite” favourite George Brown – whose choleric temperament promised a bumpy ride – and the outsider James Callaghan.

The moment was already propitious for Labour. The languid Harold Macmillan – who had succeeded Anthony Eden as prime minister in 1957 following the Suez disaster – presided over a stop–go economy and a rivalrous cabinet. Labour’s internal rancour since 1959, when it lost an election it expected to win, was easing as its mind was concentrated by the approaching contest. After three successive defeats, the next election seemed winnable, even more when the infirm Macmillan anointed the aristocrat Douglas-Home as a compromise successor.

In October 1964, Wilson clinched the deal, entering Number 10 with a bare majority of five seats, which he increased to a comfortable ninety-seven in 1966. His reforming though fractious and economically troubled government fell in June 1970. Edward Heath’s Conservatives then foundered, and Wilson was back in February 1974 at the helm of a minority government. Eight months later he won another slim majority, but two years later resigned to general surprise. From meteorite to puff of smoke, the Wilson era was over. In a sense it was also the symbolic end of “the long 1960s,” and the beginning of a short transitional period before Britain hurtled into a prolonged new age.

The first of the era’s four phases, 1963–66, was the zenith. Wilson consolidated his new leadership, assailed the Tories’ “thirteen wasted years,” and presented himself to voters as an impatient moderniser. A vigorous speech in October 1963, promising a brave new classless Britain “forged in the white heat of this [scientific and technological] revolution,” projected a futuristic confidence with traces of JFK (who, despite appearances, was only a year younger than Wilson). Along the way the “uncompromisingly dirigiste” address, in the words of his biographer Ben Pimlott, also lauded the “formidable” achievements of Soviet planning while disdaining its methods.

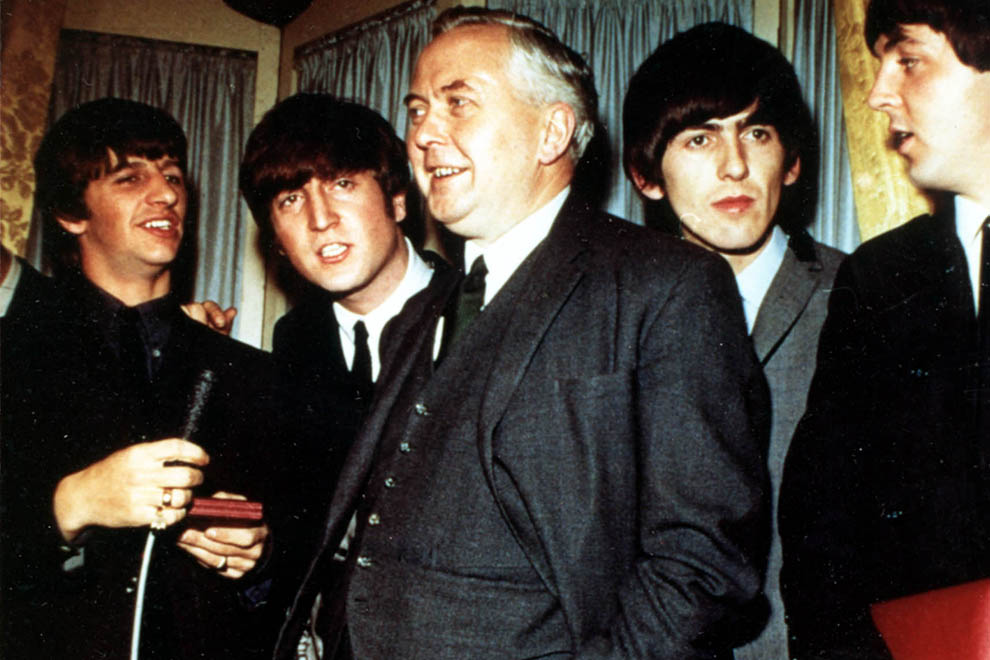

Though Labour inherited a parlous economic situation, Wilson used office to build popular support in advance of the inevitable follow-up election. Social benefits were increased, regressive taxes abolished, state bodies relocated outside London, regional policy expanded. Wilson also imprinted himself on the national imagination: he was the man with the plan, the pipe and the ever-ready quip, his populist flair (on display when he awarded MBEs to the Beatles in 1965) in rough tune with the changing times.

The second phase, 1966–70, was made tougher by a big budget deficit fuelling pressure on sterling. Wages and prices were frozen, as the already listing flagship of socialist renewal – an expansionist “national plan” – collided with Treasury fears over the currency. The plan was George Brown’s responsibility, at a new economic department created for the purpose. In an age of fixed exchange rates, devaluation as an option gnawed at ministers, but the debate was haunted by memories of 1949, when Labour’s financial credibility was battered by just such a decision.

When it came in November 1967, a cut of 14.3 per cent against the US dollar, a single sentence in Wilson’s TV address – defending a move he had long resisted – became notorious: “It does not mean, of course, that the pound here in Britain, in your pocket or purse or in your bank, has been devalued.” It was an invitation to political and press adversaries to say that the PM himself was now devalued.

Chancellor James Callaghan resigned, to be replaced by Roy Jenkins. Four months later the bibulous Brown, now a “tired and emotional” foreign secretary (the phrase was immortalised by the satirical magazine Private Eye), took one too many of his late-night resignations and found himself in the gutter, looking at the stars. By-elections turned nastier for Labour, the wounds including a savage loss to the Scottish National Party, or SNP, in Hamilton. Yet Britain’s finances did slowly rebalance, and with them the government’s prospects. By mid 1970, with an election looming, it seemed to have come through.

On political skills alone, Wilson outranked the stolid Heath. But bad eve-of-poll trade figures were an untimely reminder of the 1967 humiliation. In a languid midsummer, during the soccer World Cup in Mexico (and days after a bleary post-midnight TV audience had seen England knocked out by West Germany, which folk memory would deem significant), a fit of absent-mindedness helped put the Tories back in.

The 1960s cabinet of “big beasts of the jungle” (as the political lexicon put it) had featured all forms of animal life. The fiery socialist Barbara Castle’s efforts to formalise corporatism in the labour market were quashed by the trade unions with the backing of Callaghan, now home secretary. Jenkins’s liberal reforms in the latter job – on abortion, divorce, homosexuality, the voting age, the death penalty and theatre censorship – were a landmark stride towards (as he put it) “the civilised society,” as was the creation of the Open University under Jennie Lee, the first arts minister.

Wilson had pushed for Britain’s membership of the European Union’s predecessor, the European Economic Community, or EEC, had kept Britain out of Vietnam, and had sent troops to Northern Ireland to restore civil order. (Out of sight, though, brutal “small wars” rat-tatted through Borneo, Aden, Cyprus and Dhofar, and the Diego Garcians were ejected from their Indian Ocean home to make way for an American base.) The long-serving defence minister Denis Healey announced withdrawal of forces from “east of Aden” in 1968, as military deployment “east of Suez” (Rudyard Kipling’s poetic phrase was always preferred) became the overseas equivalent of the devaluation conundrum.

Wilson also sought close ties with the Commonwealth, a motive influenced (as perhaps was his career choice) by an enthralling sojourn in Western Australia as a fifteen-year-old in 1926. His grandparents ran a small farm near Perth, and Wilson’s uncle, Harold Seddon, was a member of the legislative council who had abandoned Labor for the National Liberal Party over conscription in 1917. The visit, says Wilson’s biographer Ben Pimlott, “gave him a first hand glimpse of the pomp and glamour of politics.” There was little of those in his exchanges with the Australian prime minister Harold Holt in the mid 1960s, in which they circled around respective adjustments in national priorities. The cold war is moving east, insisted Holt, and this underscored the importance of Vietnam: “I believe that for all the shift and change in the world, none is more important to us in Australia than the shift of international tensions from Europe to Asia.”

Wilson’s default pragmatism fitted Britain’s foreign-policy juggling act. Beyond this home ground, his grander assertions reflected less deep purposefulness (a favourite word) than accommodation to orthodoxies he was unable to change or unwilling to confront. “Britain is a world power or it is nothing,” Wilson had said, the arch moderniser voicing an ancestral instinct. From another pool of the same vast deep he had declared in 1962: “The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.” After almost six years at the helm, the quip-master’s words had an ample record against which to be judged.

The third phase of the Wilson era, 1970–74, was an interregnum, in opposition to a Conservative Party newly committed to a bold program of slashed controls and market discipline as the route to economic revival. The experience of 1963–64, when he had faced the tweedy paternalism of Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home, was no guide against his contemporary Edward Heath, another provincial grammar school boy with an Oxford degree. Jibes about a Conservative leader’s aristocratic lineage or fondness for the grouse moor no longer applied, while any targeting of Heath’s favourite pursuits, sailing and piano playing, would be otiose.

Instead, Wilson mocked “Selsdon Man” – after the hotel where the Tories’ rightward march was agreed – who was “designing a system of society for the ruthless and pushing, the uncaring.” The trouble, as Alwyn Turner suggests in his brilliant Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s, is that Tories looking for a new direction, for so long ridiculed as members of the “stupid party,” wore the imputation of ideological coherence with pride.

Labour was winded by its shock defeat, and those near the summit of the “greasy pole” were forced into instant recalibration of their own and the party’s prospects. But Wilson’s position was not a priority. Six exhausting years in government had taken their toll, and time to reflect was needed. Labour leaders, even losing ones, tend to go in their own time.

Moreover, none of the potential candidates was quite ready. There was no shortage of them: Callaghan, Jenkins, Healey, Shirley Williams, Anthony Crosland on the right, Castle and the metamorphosing Tony Benn on the left. (Tony “immatures with age,” would be Wilson’s verdict on the former technology minister. Benn was just as comradely in return, a diary entry in June 1969 describing Harold as “a small man with no sense of history and as somebody really without leadership qualities.”)

Such frayed relationships, in part the inevitable result of governing through crisis, also reflected dislike of Wilson’s political character and operating style. Few of his colleagues would credit him with clear purpose or ideas. A good party manager, a witty performer in the House of Commons and on TV – that was about the best of it. The vacuum bred suspicion on both sides, accentuated by Wilson’s penchant for what Richard Crossman, former housing and health minister, called “prime ministerial government.” Wilson was ever attuned to cabinet plots, real or imagined, his fears stoked by cronies such as the bloodhound George Wigg, his confidence by his loyal press secretary Joe Haines and secretary Marcia Williams. Rumours of palace coups swirled with the cigarette smoke around every Labour conference. “I know what’s going on!” declared Wilson from the platform at a packed London rally in May 1969 – long pause for effect, nervous laughter in the hall, then – “I’m going on!” Cue relieved cheers, but that he had to say it was telling.

Distrust of Wilson had deeper roots. It had seeped across both wings of the party since at least 1951, when, with Aneurin (Nye) Bevan and John Freeman, he resigned from Attlee’s government over health charges, then chaired Bevin’s “Keep Left” group, only to accept a shadow job under Gaitskell in 1955 after switching sides. In 1960, he reacted to Gaitskell’s conference defeat over reform of Clause IV of Labour’s constitution, which in effect enshrined state control of the economy as an aim, by seeking to replace him as leader. “If there were a word ‘aprincipled’ as there is a word ‘amoral’ it would describe Wilson perfectly,” Freeman had said in 1951.

An external source of criticism in 1971 was the BBC documentary Yesterday’s Men, depicting Wilson as a political has-been who had earned a vast sum from the serialisation of his memoirs in the Sunday Times. The ensuing row amplified the program’s impact, with Labour seeing it as a vengefully titled media stitch-up. (Wilson had minted that very phrase to describe his Tory adversaries in the 1970 campaign.)

The memoirs, which became a bestseller, reflected a choice use of energies for an opposition leader in mid-career facing a stiff fight to recover power: an 800-page tome on the 1964–70 governments, written in the mandarin prose of the civil servant Wilson had been until he became an MP in 1945 but sprinkled with what the Guardian’s Ian Aitken called his own “cutting retorts, crushing witticisms and icy repartee.”

Behind The Labour Government 1964–70: A Personal Record was another source of tension in the former cabinet. Wilson knew that several colleagues (Benn, Castle, Crossman) had kept records, perhaps with an eye to a future when the restrictive official codes on publishing had been breached. Crossman’s diaries became the pivot of that quasi-constitutional tussle, three volumes eventually appearing in 1975–77. Wilson was to make sure that the first draft of history, filleted to avoid undue controversy but also to enhance his own status, would be his.

Labour’s uneasy adjustment to opposition received succour from a Conservative government of remarkable ineptness, which veered off its intended course almost from the start. Its economic policies, including the lifting of price controls, stoked inflation even before the first oil shock hit in 1972. Its frenetic “Barber boom,” named after Heath’s chancellor, was springtime for spivvery in property and construction. Its confrontational attitude towards the trade unions was more than reciprocated, but lacked political nous. It sought market-friendly reforms but was unable or too arrogant to build a consensus in their favour.

Edward Heath fulfilled his career’s ambition in 1972 by negotiating Britain’s accession to the EEC. But a coalminers’ strike the same year, and an exploding conflict in Northern Ireland, compounded the growing sense of embattlement. (A surviving recording of Heath’s response to the entreaties of the moderate Irish taoiseach Jack Lynch after the British army massacred protesters in January 1972 is a chilling study in prime ministerial incomprehension.) When the miners came out again in 1974, the government’s emergency response – a three-day working week to save energy – culminated in Heath’s calling an early election on a “Who governs the country?” ticket.

The Conservatives’ strategic drift meant Labour could stay in the game without serious test. On its side a renascent left exerted strong influence in key policy reviews, committing the party to a socialist manifesto (“and we are proud of the word”) which promised “a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people and their families.” Wilson was an unlikely conduit for such an aspiration: the leader was now balancer-in-chief, his own offer to the country no longer dynamism but reassurance.

The act worked, insofar as Heath lost the election in February 1974 and had to resign after being unable to do a deal with the Liberals. That party’s advance, and that of the SNP, was a crack in two-party dominance, but the overall distribution of seats made Labour the beneficiary, allowing Wilson to become prime minister. Labour settled with the miners, patched up a “social contract” with its trade union allies, junked the Tories’ labour laws and went to the country in October, carving out an overall majority of just three. This was no reprise of 1966: Labour loyalties were no longer as automatic or easily won. (Then, Labour had taken 47.9 per cent of the vote, now the figure was 39.3 per cent.) For Wilson, though, it was a degree of confirmation for his claim that, despite the reversal of 1970, Labour had become “the natural party of government.”

In the aftermath of their second defeat in a row, the Conservatives lived up to two of their noble traditions: defenestrating a loser and enthroning an outsider. In the first, courteous exchange across the despatch box, Wilson played the experience card by saying that he had “worked closely with her three immediate predecessors.” In reply, Margaret Thatcher upheld “the mutual respect of keen antagonists which I think is in the best interests of parliamentary democracy.”

The fourth phase of the Wilson era, 1974–76, thus got under way with roles reversed as compared to 1963–64: he was now the establishment figure, his opponent the ambitious insurgent with an acid tongue (if hardly wit). The freshness of 1963 was long past. As Pimlott, his sympathetic biographer, observes, “He was a survivor; yet survival for what?” Yet people and society had changed too, and in uncharted times Wilson now had the asset – never, in Britain, to be discounted – of familiarity.

Industrial strife and raging inflation were Labour’s priorities. The Irish Republican Army, or IRA, made itself another when it killed twenty-one people in Birmingham a month after Labour came to power, provoking home secretary Roy Jenkins to introduce emergency anti-terrorism legislation. (Wilson himself had met IRA leaders in Dublin in 1972 in an effort to break the deadlock.) The new government’s survival also depended on its handling of EEC membership. Labour’s manifesto had brokered the party’s irreconcilable positions by offering the ambiguous promise that the people would have a chance to decide the issue “through the ballot box.”

Labour’s divisions were symbolised above all by the vehemently anti-EEC Benn and the passionately pro-European Jenkins. Benn proposed a referendum as a way through them, he hoped, to the exit. Wilson himself, tactical considerations to the fore, came round to the idea. (Attlee, recalling Austria’s annexation in 1938, had called it a “device for despots.”) He undertook a round of talks with Britain’s new partners that yielded nominal concessions, suspended “collective cabinet responsibility” for the duration of the campaign, and recommended to party and country that they could vote in good conscience to remain in the EEC. It would be the first ever UK-wide referendum.

Most opinion split across conventional party, class and ideological lines, though partisans of European federalism or sovereign independence made common cause with erstwhile opponents. Wilson’s stance in favour of continued membership was backed by pragmatic Labourites, while the Conservative and business case weighed heavily against the left and trade unions’ advocacy of withdrawal.

In the vote on 5 June 1975, the result was clear: on a 65 per cent turnout, over 67 per cent thought “the United Kingdom should remain part of the European Community (the Common Market).” Britain’s future in Europe was assured – at least, as it has turned out, for forty-one years. On 23 June 2016, after a comparable package of modest reforms negotiated by the Conservative prime minister David Cameron, Britons will again vote on whether to remain in or leave what is now the European Union.

The contest had also been a right vs left battle over Labour’s direction, which the referendum only accentuated. (This year’s campaign is so far proving very much a right vs right – and intra–governing party – one, with Conservative schisms monopolising the debate and Labour barely visible.) Nonetheless, Wilson could claim, if sotto voce, to have added another national vote to his impressive notch. He took the opportunity for a reshuffle, demoting Benn from the industry portfolio to energy, then resumed the slog of governing with a knife-edge majority through a post-Keynesian world of high inflation and unemployment. In mid 1970s Britain, there were no glad confident mornings on offer.

Fifteen months later, in September 1976, the Labour prime minister would give a stern warning to conference against “superficial remedies” in the economy. Today’s problems are the result of “paying ourselves more than the value of what we produce.” A low-tax, high-spending response would make things worse: “I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists.” The speaker was Wilson’s successor, James Callaghan, the speech (written by the journalist Peter Jay, a rare centre-left monetarist) arguably historic both in its content and its challenge.

Harold Wilson had resigned in March, stunning first his cabinet, and then the press and the country. (“I felt as if his presence had filled the best years of my life. It was like the death of an estranged father,” recalled the Guardian journalist Peter Jenkins.) Only the inner circle knew of a decision made, it seemed, the previous year. He had just turned sixty and, disappointed at winning only a tiny majority last time, had lost the spark. It was not a “sudden” decision, says Pimlott, but on the contrary “long planned.”

The explanation was too neat for many, and rumours flourished – most of them espionage-related. Wilson had sought cooperation with the Soviet Union, it was noted, which would interest intelligence agencies on both sides of the cold war. Suspicions of “rogue” elements in MI5 out to get Wilson, such as Peter Wright of Spycatcher, bubbled on. Wilson had fuelled the chase with an interview soon after leaving office that suggested at least mild paranoia, before settling to a less exacting routine. He was re-elected an MP in 1979, ascended to the House of Lords in 1983, accepted fellowships and wrote books, before his memory weakened considerably from the mid 1980s. (The third volume of memoirs, published in 1986, had to be ghostwritten.)

Less conventional was a brief foray into TV as host of a chat show whose two excruciating episodes hinted (as perhaps had that interview) at a decline in his mental powers. Much later this would be adduced as an early indicator of the dementia that would overtake him, shadowing his retreat from public life until his death in 1995. By then, two decades after he had departed, Wilson and his period had faded from view: the devaluation saga ancient history, the “three-day week” that helped him to power in 1974 overtaken in public memory by the 1978–79 “winter of discontent” that did the same for Thatcher.

Though time and technological change would have done much of the same work, Thatcher’s own era thickened the fog that settled over Wilson’s. He was even eclipsed by the congenial Callaghan, who was liked by the public and respected in cabinet, and whose decision not to call the election in late 1978 (when polls were encouraging for Labour) is one of postwar British history’s big what-ifs.

Wilson’s reputation as a wily tactician with no deep convictions and a weakness for cronyism endured, though Pimlott’s 700-page biography, published in 1992, did an impressive job of rehabilitation. For all his political achievement, even supportive observers continued to qualify their judgement: “somehow, real success evaded him,” the veteran former Daily Mirror journalist Geoffrey Goodman, who knew Wilson well, wisely concluded in his obituary.

Whatever the political weather, Wilson’s triple anniversaries – birth, decisive election win, resignation – would be grounds enough for a media splash. The coincidence of the European Union referendum, now dominating the political agenda, adds a topical element. Wilson’s ubiquity through the packed years from 1963 to 1976 means that other contemporary resonances are everywhere, including the realm of popular culture that he was skilled at tapping.

His faintly vaudevillian aura, his allegiance to a soccer team (now a mandatory requirement of the job), his affinity with the demotic northernist glamour fashionable in the early 1960s: all offer familiarisation to time travellers from the future. The flipside of such soft-power connections between past and present is that only hard politics can bring improvement to the lives of millions of people in a democratic society, or even resolve matters over which there is deep disagreement. Wilson at his best, however, taught that hard politics – and modern politicians – need soft power to do the job.

Wilson’s breakthrough in 1964 is closer to the start of the Great War than it is to today. Yet it holds a contemporary, indeed eternal lesson. In Britain, a long spell of Conservative government tends to make even those outside the Labour family look expectantly for a centre-left leader with a national popular appeal and a convincing economic argument, the essential requirement for progress then as now. The long 1930s, 1950s and 1980s were all, by contrast, exercises in prolonged mugging by reality. So have been the 2010s. It might take until the 2020s, but today’s desperate Labour Party will eventually relearn the same truth. Then Harold Wilson will have earned another statue. •