An electoral thriller is looming in Melbourne’s inner south. We owe it to a subtle boundary change that escaped notice in this week’s redistribution of Victoria’s federal electorates by the Australian Electoral Commission.

Media coverage has focused, naturally, on the fact that Labor can hope to gain at least two seats from the redistribution, and possibly three. Having lost thirty-four consecutive Newspolls, the Coalition could have done without that aspiration.

Fraser, the new seat gained by Victoria as a result of its rapid population growth, will be in safe Labor territory in the western suburbs around Keilor and St Albans. The new boundaries will also see the outer-suburban Frankston seat of Dunkley switch from marginal Liberal to marginal Labor.

And the southwestern seat of Corangamite, now reduced to cover essentially the coastal resorts and the hinterland of Geelong, will become a lineball electorate, with my fellow psephologist Ben Raue of The Tally Room estimating that Labor will need a swing of just 0.1 per cent to retake it from Liberal MP Sarah Henderson.

Against that, South Australia will lose a seat — almost inevitably a Labor seat — in Adelaide. And in Victoria, other marginal Liberal seats such as Chisholm, La Trobe and Deakin will become appreciably safer under the new boundaries.

But the most intriguing of all the Victorian seats at the coming election will be the three-way contest for the bayside seat we have known since Federation as Melbourne Ports. (It will be renamed Macnamara — after medical scientist Dame Annie Jean Macnamara — under the commission’s policy of evening up the gender imbalance by naming as many electorates as possible after women. Why can’t it name them after places rather than men or women, so we all know where they are?)

Melbourne Ports has always been a Labor seat. Labor has won it at forty-three elections in a row, an unbroken run of 110 years. Its former members include Frank Crean, the first of three treasurers in the Whitlam government, and former Hawke government minister Clyde Holding. But no other area of Melbourne has undergone such a transition over the past fifty years.

Port Melbourne, which used to be one of the poorest areas of Melbourne and the home of wharfies and other dock workers, is now an upmarket, Liberal-voting area of posh apartment blocks with bayside views. Middle Park has become one of Melbourne’s richest suburbs. The electorate as a whole, according to the 2011 census, is now the third-richest in Melbourne.

The redistribution commissioners have further shifted the balance by adding 5000 voters from funky inner-suburban Windsor. (The draft report has the details.)

Labor will not only be under threat from both sides, but the boundary shifts will also virtually wipe out its lead over the Greens.

Even in 2016, Melbourne Ports ended up as the second-closest contest in the entire House of Representatives. Labor MP Michael Danby outpolled the Greens by just 953 votes at the three-party stage of the contest, then Greens preferences allowed him to overtake the Liberals to win by 2337 votes. But a swing of just 0.56 per cent from Labor to the Greens would have seen them swap places, and potentially given the Greens a second seat in the House.

On my estimate, the addition of Windsor effectively closes the gap between Greens and Labor. In 2016, after preferences from minor candidates, the Greens won the Windsor polling booth with an absolute majority over the Liberals and Labor combined.

At the neighbouring booths of Prahran and Prahran East, the Greens topped the count at the three-party stage, and my time-tested assumptions suggest that they ran a close second to the Liberals on all the non-booth votes — pre-polls, postals, absentees and so on — that made up almost half the votes cast in the electorate.

While any estimate of the vote after a redistribution can only be a rough one, my estimate is that on the new boundaries, Labor’s margin over the Greens in 2016 would have shrunk to just seventy-six votes, or 0.05 per cent. Given that we can’t know exactly where pre-poll and postal votes came from, that’s a virtual dead heat.

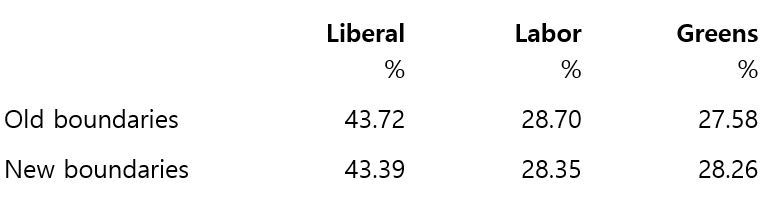

This is the breakdown at the three-party stage:

On my estimate, Labor’s margin over the Liberals would swell slightly, from 1.4 per cent at the 2016 election to 1.6 per cent. (Two fellow psephologists have estimated that adding a Greens stronghold to the electorate will improve the Liberals’ chances, but that seems to me quite implausible.)

The long-term trend in Melbourne Ports has seen Labor’s vote peel away on both sides, thanks to the gentrification of the former working-class suburbs from Port Melbourne to St Kilda — and the bizarre dogleg extension of the electorate into quiet Liberal-voting suburbs to take in as much as possible of Melbourne’s Jewish community.

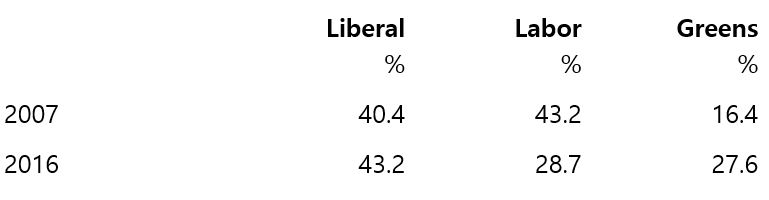

In the three elections since 2007, the change at three-party level has been startling.

Some in Labor blame Michael Danby and his intense focus on issues relating to Israel and the Jewish community. He distributes his own how-to-vote cards, putting the Greens last for supporting Palestine, and once flew to Israel to attend a conference while officially on sick leave from parliament. Like former Batman MP David Feeney, he is seen as pushing voters from Labor to the Greens.

But there is no electoral evidence for that. Labor has lost votes to the Greens throughout Melbourne’s inner suburbs, and Melbourne Ports is far from the worst example. A comparison of House and Senate votes in 2016 suggests that while Feeney dragged down Labor’s vote in Batman, Danby raised Labor’s vote in Melbourne Ports — presumably by attracting Jewish votes from the Liberals.

The Greens have re-endorsed environmental lawyer Steph Hodgins-May as their candidate for the seat after she came so close last time. Labor and the Liberals have yet to choose their candidates.

An intriguing question is what would happen if the Greens did tip Labor into third place, then relied on its preferences to win the seat. If Labor voters allocate preferences as they did last time in next-door Higgins — which included Windsor — then my estimates give the seat to Hodgins-May with 51.6 per cent of the final vote.

But in Higgins, 82 per cent of Labor voters gave their preferences to the Greens. The Liberals’ share of Labor preferences would need to rise only from 18 to 23 per cent for them to win the seat. If Danby again produces his own how-to-vote cards giving preferences to the Liberals, that could well give them the seat — and even decide who wins government.

All this may become irrelevant. On conventional political wisdom, the Turnbull government’s success in getting its huge income tax cuts through parliament should tip the scales when we go to vote, even if the polls are against it.

Some of us remember the 1980 election, when the polls pointed to a solid Labor win but the Coalition was re-elected after a last-minute scare campaign on capital gains tax; we will never underestimate the power of the hip-pocket nerve.

But there are signs that those instincts have diminished. The Howard government also offered huge income tax cuts in 2007, only to be swept from office. Both sets of tax cuts favoured the rich and were fiscally irresponsible — it is reckless to legislate now for big tax cuts in four or six years, when we don’t know what the economy or the budget will be able to afford. Voters cared about the national debt in 2013. Whether they still care about it now is unclear.

The tax cuts will help to define Turnbull, whose prime weakness is that he’s seen as not standing for anything. His former supporters appear to have switched off. Will the prospect of paying less tax make them listen to him now? Interesting times ahead. ●