It seemed like a bolt from the blue. At November’s Pacific Island Forum in the Cook Islands the prime ministers of Australia and Tuvalu announced they had signed the Falepili Union treaty, named after the Tuvaluan word for close neighbours. Under the deal, Canberra committed itself to resettling Tuvaluan citizens and supporting the island nation’s climate change adaptation, and Tuvalu agreed to closer “cooperation for security and stability” in what has been widely interpreted as giving Canberra veto power over its security arrangements.

As surprising as the announcement might have seemed, a long history lay behind it. Until the first meeting of signatories to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, in 1995, Canberra was largely seen as being on the same page as other Pacific nations (outwardly, at least) on climate change concerns. Then, at a tense South Pacific Forum meeting in 1997, prime minister John Howard refused to sign up to binding targets for emissions reductions. Other Pacific leaders eventually relented, agreeing instead that nations would “adopt different approaches” at the upcoming Kyoto talks.

Has prime minister Anthony Albanese finally repaired the “climate rift” with Australia’s Pacific neighbours? Although Tuvaluan critics of the Falepili Union treaty are rightly sceptical of Canberra’s commitment to climate justice, Mr Albanese was among the leaders who assented to the Forum Communiqué’s aspiration for what it labelled “a Just and Equitable Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific.” In doing so, they echoed the Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific made by six Pacific countries, including Tuvalu, in March this year.

That call reflects an international effort to negotiate a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty inspired by the 1968 nuclear non-proliferation treaty. Advocates argue that such a treaty — unlike the Paris climate agreement, which doesn’t explicitly name coal, oil and gas — would directly target their phasing out and outline a plan for a fair transition to clean energy.

If the phrase “a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific” rings a bell, you’re not mistaken — the phrase gestures to the campaign for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific that began in the mid 1970s. In 1985, with France continuing its nuclear weapons testing on Mururoa atoll and anxieties deepening about US military installations on Australian soil, those efforts culminated in the declaration of the South Pacific as a Nuclear Free Zone in the Treaty of Rarotonga. The French had bombed the Rainbow Warrior just a month earlier.

But the link between nuclear weapons and climate change goes well beyond inspiration. Historians have excavated how nuclear weapons testing shaped the US cold war–era science that shed light on the mechanisms of global warming. Likewise, the scientific debate over a nuclear winter helped to convey the possibility of widespread human-induced destruction on such a scale that even non-combatant nations would be affected. A nuclear war would have no winners.

Climate change was now seen as an issue the world’s governments should tackle multilaterally. As concerns about ozone depletion and acid rain had shown, the atmosphere respects no territorial borders.

This message was articulated clearly in the statement arising from June 1988’s Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security conference in Toronto. “Humanity is conducting an unintended, uncontrolled, globally pervasive experiment whose ultimate consequences could be second only to a global nuclear war,” agreed the largest such gathering of scientists and policymakers to date. Participants called for a global convention to coordinate scientific research and spell out concrete measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Nearly four decades later, security returned to centrestage in Chris Bowen’s annual parliamentary climate change statement last month. “The currently identified national security threats from climate change already present serious risks to Australia and the region, but they will become more severe and more frequent the further warming targets are exceeded,” the climate change and energy minister argued. “Climate change is an existential national security risk to our Pacific partners and presents unprecedented challenges for our region. It is likely to accentuate economic factors already fuelling political instability, including risks to water security across the globe.”

The implication of rising temperatures for the world’s coastal areas — home to half of humanity — was an early concern of scientists and policymakers responding to climate change. This vulnerability was especially clear in the Maldives, where storm surges in early 1987 had flooded the capital, Malé. After president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom raised the issue at that year’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting and then at the UN General Assembly, the Commonwealth Secretariat commenced its own study of the likely effects of climate change on its member nations, which in turn commissioned studies of the Maldives, Tuvalu, Kiribati and Tonga.

With Malta prepared to raise climate change at the General Assembly in late 1988, the South Pacific Forum discussed the issue at its October meeting in Tonga. It joined other pressing concerns for the region, including fisheries exploitation, political upheaval and telecommunications. Subsequent gatherings of Pacific and other island nations in the Marshall Islands and the Maldives reiterated the existential threat that rising sea levels posed to their countries.

A 1989 booklet, A Climate of Crisis: Global Warming and the Island South Pacific, described the looming threat as a “climate bomb” that “threatens the physical and cultural survival of several Pacific societies. They are the innocent victims of the northern hemisphere’s 300-year orgy of fossil fuels.” Announcing Australian funding for a regional network of sea level monitoring stations in August 1989, prime minister Bob Hawke explained that it would help “ensure that we are well aware of what the region is in for.” Pacific concerns were reiterated at that October’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Malaysia, where leaders responded to the Commonwealth Secretariat’s report with the Langkawi Declaration.

Australia’s own scientific research on climate change meant Canberra was well aware of its implications for the Pacific. Following Malta’s call for the “Conservation of Climate as part of the Common Heritage of Mankind” in October 1988, Australia’s representative at the UN General Assembly, Michael Costello, expressed Canberra’s concern about the “potential for climate change to cause serious economic and social disruption in countries of the South Pacific and Indian Ocean regions.”

The following year Tuvaluan prime minister Tomasi Puapua described to an Australian parliamentary committee the “possible impact of the greenhouse effect on his country,” which was “one of Tuvalu’s major security concerns.” Climate change represented a “potentially catastrophic” threat to the “very existence” of atoll states like Tuvalu, the committee reported. “In the worst scenario the entire populations of these small states may end up as environmental refugees, seeking resettlement in countries such as Australia.”

Canberra’s framing of Pacific island vulnerability as a security issue reflected almost a decade of assessing the prospects of newly independent and decolonising neighbours like Tuvalu. Nor had the Soviet Union’s recent efforts to extend its influence in the region gone unnoticed. “Environmental problems, if unchecked could threaten our security,” warned Australia’s foreign minister, Gareth Evans, pointing to the “devastating effect [of rising sea levels] on the small island countries of the South Pacific.”

Echoing concerns voiced in the United States and Britain, Evans anticipated hundreds of thousands of “environmental refugees” “who would look mainly to Australia for resettlement.” “In short,” he argued, “quite apart from the cost in human misery and dislocation to the island communities, which of course are ample reasons in themselves for our concern, it would jeopardise vital Australian national interests.”

Puapua’s successor as Tuvalu’s prime minister, Bikenibeu Paeniu, continued to assert the vulnerability of island nations on the world stage. In the wake of Cyclone Ofa and early meetings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, he told the Second World Climate Conference in late 1990 that it would be “an injustice should we in Tuvalu and the island nations, be denied our right to live in our homeland.” He continued: “We contribute little or nothing to the problem and yet we will be the first to suffer. Our survival is at stake.”

Although the island nations were ultimately disappointed with the climate conference’s pared-back ministerial statement, they came away from Geneva having formally organised themselves as the Alliance of Small Island States, or AOSIS. With the legal support of the recently formed British group, the Foundation for International Environmental Law and Development, the island nations understood that their interests might be better served collectively as a UN bloc in the upcoming negotiations of the UNFCCC.

Australian negotiators were quietly sceptical of the motives of larger developing nations, which they believed to be more interested in a renewal of the New International Economic Order. But they acknowledged the difficulties facing small island nations. After a meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee of the UNFCCC in late 1991, they reported to Canberra that AOSIS members were “genuinely worried about the adverse consequences for them.” As the small island states had stressed during the negotiations, “The very existence of low-coastal and small vulnerable island countries is placed at risk by the consequences of climate change.” Although AOSIS sought more ambitious provisions, the final text of the UNFCCC would go on to explicitly acknowledge their particular vulnerability to the “adverse effects of climate change.”

Australia was one of the first signatories to the UNFCCC at the Rio Earth Summit in mid 1992. The AOSIS nations followed soon after, including Nauru, Tuvalu and Kiribati, which were not yet UN members. Upon signing what they saw as a weak treaty without targets or timetables for emissions reductions, that trio joined with Fiji to expressly declare that were not renouncing their rights under international law concerning state responsibility for the adverse effects of climate change.

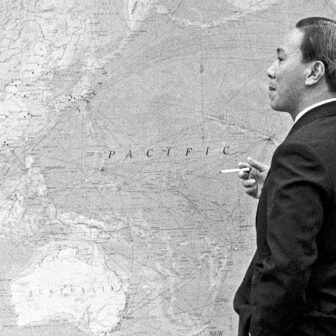

The Earth Summit offered Prime Minister Paeniu an opportunity to share Tuvalu’s position with a much broader audience. Thanks to the promotional efforts of Greenpeace, he addressed a full press conference on the implications of rising sea levels for his country. “There would be no land left for us,” he said. “There cannot be any other home for Tuvalu. Even if we were offered 10,000 acres in Australia, it won’t be the same Tuvalu.”

This was the scenario to which the leaders assembled at the recent Pacific Islands Forum returned. Having made a declaration on the preservation of their maritime zones in 2021, they now called for the preservation of their statehood and cultural heritage in the face of climate change–related sea level rise. Fearing the worst, Tuvalu had already set out to become the First Digital Nation — a project Funafuti hopes “will allow Tuvalu to retain its identity and continue to function as a state, even after its physical land is gone.”

Despite the existential threat that climate change poses, successive COPs have demonstrated the challenge of making manifest a planetary ethic for real global climate action. As in the late 1980s, however, asserting the security implications of climate change continues to allow for the alignment of territorial interests with atmospheric concerns that don’t recognise political borders.

Those territorial interests are really what’s at stake when government negotiators descend on cities like Paris and Dubai for what have become annual climate talks. For all the hot air those talks produce, there remains room for hope: regardless of territorial size or emissions, every party has a single vote on the future. •