Blueprints to reform Australia’s woeful electricity system are coming in so fast they blur into each other. And they’re coming because, after such a long debate, we are nearing the moment of decision.

Thankfully, much of the territory covered in the debate is now common ground between the Coalition and Labor. But key gaps remain, and everyone wants a say in the outcome. A final bipartisan agreement on the structure for Australia’s energy and emissions policies is within reach — but it does require common sense to prevail, especially on the Coalition side. In energy policy, that’s no certainty.

The outcome matters for three reasons. First, in just ten years, electricity and gas prices for Australians have doubled. From being among the cheapest in the Western world, they are now among the most expensive. Electricity prices are the reason battlers are angry about the rising cost of living. And those prices are threatening the existence of our energy-intensive industries, which set up here because we had cheap power and now find it is so expensive it could put them out of business.

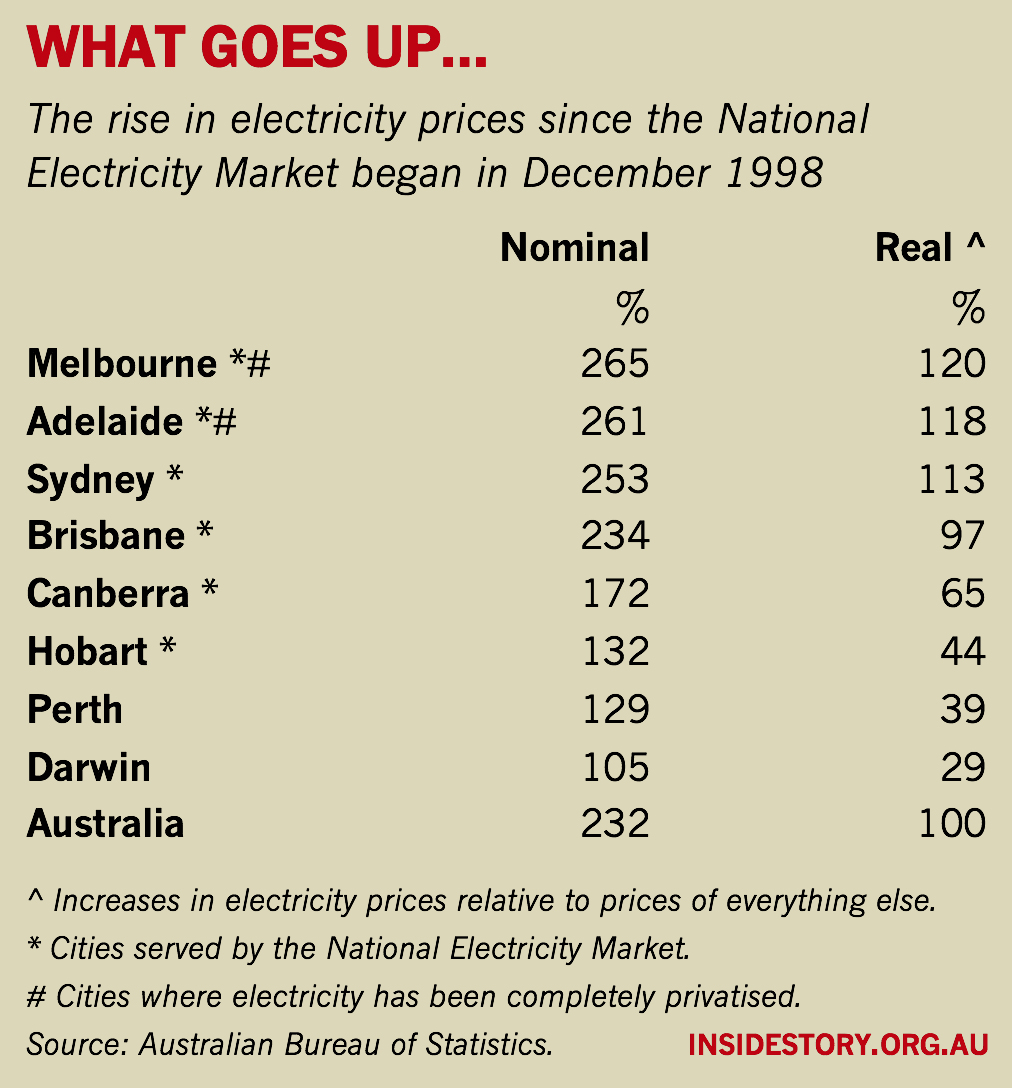

Here’s the evidence. Since the birth of the National Electricity Market, or NEM, almost twenty years ago, power prices have risen by 232 per cent nationally — and by 100 per cent in real terms, relative to the prices of other goods and services.

Prices have risen far higher in the east coast cities, where the NEM operates, than in Perth and Darwin, where it doesn’t (or in Hobart, where it’s made little difference). Moreover, the more privatised a city’s electricity system is, the more its prices have risen. That is not what the regulators or the politicians want to hear, but it is what the evidence is telling us.

The contrast between east and west shows that the national market has been a failure. We want electricity and gas prices to fall substantially. And two reports by government agencies in recent days propose reforms that they argue will do that.

The second reason why an agreement matters is that global governments, including Australia’s, have promised to reduce or reverse emissions growth to keep global temperatures no more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels. But most governments, including Australia’s, have shrunk from implementing policies that would deliver the targets they signed up to.

Tony Abbott is calling on Australia to abandon his pledge in Paris three years ago to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 to 26–28 per cent below their 2005 levels. But the Turnbull government has already effectively abandoned that commitment by promising to reduce electricity emissions by only that amount — although they are by far the easiest and cheapest emissions to reduce and so could support greater reductions.

The government’s own figures show that Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions grew from 516 million tonnes to 534 million tonnes between 2013 and 2017. To meet the Paris target, emissions would need to shrink to roughly 450 million tonnes by 2030. There is no sign of that happening. Last year, emissions grew by 1.25 per cent — despite the closure of the Hazelwood power station, Australia’s single worst polluter.

Of the two latest government reports — from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and the Australian Energy Market Operator — one sets out a road map for meeting the government’s modest target while the other, for all its strengths, ignores the target and proposes a change that could threaten even that.

The third reason is energy security. The only power plants being built in Australia are wind and solar; they rely on nature, and nature does not commit to supply power when we need it. Look ahead, and in a renewables-based future we will need to also meet our energy needs when the sun is not shining and the wind is not blowing. For the right, that means new coal-fired stations. For the policy-makers, it means a mix of existing coal and gas stations, batteries to store solar and wind energy, hydro power using pumped storage, and contracts with large customers or groups of customers to cut off their power when a crisis looms.

That’s the context of our long, bitter energy policy debate. It is about to come to a head, with environment minister Josh Frydenberg trying to get the states (and, in effect, federal Labor) to sign up next month to the government’s plan for a National Energy Guarantee, or NEG, as a policy framework for meeting whatever emissions targets the government of the day decides.

And it’s the context for the mob of reports that have assembled in recent days. Last week began with a warning from the Grattan Institute: “Get used to high energy prices.”

Grattan analysts Tony Wood and David Blowers argue that while wholesale (generators) electricity prices have doubled in two years, the reasons were largely beyond government control, and while some reforms would help trim them, any lowering of prices will be minimal.

That message barely had time to register before the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission released its diagnosis of why Australia’s electricity has become so expensive. The ACCC proposes reforms it says would slash up to $420 a year off the high electricity prices we’ve just been told to get used to — including a very conditional government guarantee to help new generators into the market.

“PM Weighs Coal Fix for Energy Wars,” shouted the Australian, reporting that Nationals MPs and Tony Abbott saw the report as calling for new coal-fired (or “baseload”) power stations. No, replied Malcolm Turnbull, my government is technology-neutral. And ACCC chairman Rod Sims said the firms that had raised the guarantee idea with him were working on potential gas generators or pumped storage, not coal.

Then the Australian Energy Market Operator, or AEMO, issued its own “integrated system plan,” telling us we could save billions of dollars a year by focusing on upgrading transmission links between the states to provide future energy security, rather than building new generation powered by fossil fuels.

“King Coal to Rule for 20 More Years,” shouted the Australian. No, the AEMO plan foresees no new coal-fired station whatsoever. It merely suggests that some existing ones be renovated so that they last fifty years rather than thirty or forty. In twenty years’ time, on its “neutral” projection, only 18 per cent of east coast electricity will be generated by coal. Some kingdom.

We could also throw in the International Energy Agency’s annual World Energy Investment roundup, released this week, which reports that commitments were made last year to build just 31 GW (gigawatts) of new coal-fired generation — down by almost two-thirds in two years from the 87 GW approved in 2015. China still accounted for half of that, though its investment fell even faster than the rest. India committed to build just 5 GW, equivalent to two Bayswaters. The aversion to coal is worldwide.

The AEMO blueprint is a key document, since AEMO coordinates what we call the National Electricity Market, although it actually covers less than three-quarters of Australia’s electricity use (essentially, the eastern seaboard, Tasmania and South Australia). It is effectively a detailed map of how we will achieve our goals of cleaner generation and (hopefully) cheaper electricity without risking our energy security.

AEMO has four key things to tell us — and the politicians.

1. From here on, almost all electricity investment will be in renewables — mainly solar, but also wind and hydro, including pumped storage and battery storage for the solar and wind plants (as will be required under the NEG). But it suggests that, to ensure energy security in future, New South Wales could use a second gas unit as well as the 300 MW station AGL is planning to build as part of its suite of new generation to replace Liddell.

2. To further ensure security while keeping prices down, owners of the newer existing coal-fired plants should plan to renovate them so they can keep running until they are fifty years old. As AEMO’s chief executive Audrey Zibelman puts it, it’s like refitting an old car because it’s cheaper than buying a new one.

3. We could save a lot of money by upgrading transmission links between the states and, when local electricity production falls short, importing surplus electricity from interstate rather than building expensive but rarely used power stations as backups. Links between all states in the grid would be expanded massively over the next twenty years.

4. Solar and wind energy will become the mainstay of Australia’s electricity generation, and to minimise transmission costs, suitable areas in each state should be defined as Renewable Energy Zones and their transmission links upgraded.

And coal? That issue has been dealt with already by the market. No coal-fired station has been built in New South Wales or Victoria this century, and none in Queensland for the past decade. No one is planning to build one. The professionals know that the world will have to reduce carbon emissions, and investing in coal would be a big financial and environmental risk. And while it might be cheap to keep an old coal station going as long as you can, building a new one is another matter.

The AEMO report does the sums, and comes up with the same conclusion: “The least-cost transition plan is to retain existing resources for as long as they can be economically relied on,” it says. “The delivered cost of energy from wind and solar in combination with storage from pumped hydro and batteries is anticipated to be lower than generation based on new coal or natural gas when the existing coal generators retire.”

It goes on: “The analysis projects the lowest cost replacement… will be a portfolio of resources including solar (28 GW), wind (10.5 GW), and storage (17 GW and 90 GWh, or gigawatt hours), complemented by 500 MW of flexible gas plant and transmission investment. This portfolio in total can produce 90 TWh [terawatt hours] net of energy per annum, more than offsetting the energy lost from retiring coal-fired generation.”

In the next twenty years, the market operator sees the capacity of coal-fired generators in the grid shrinking from 23 GW to 9 GW, as most of the old stations reach the end of their working lives. In New South Wales, Eraring, Bayswater and Vales Point would follow Liddell into retirement. In Victoria, Yallourn would follow Hazelwood out, while Queensland would farewell Gladstone, Tarong and Callide B. Even by 2030, and without further policy shifts, coal would produce less than half the power in the grid.

It’s a measure of Audrey Zibelman’s political skills that she has produced a report that seems to have compromised nothing important yet has been greeted warmly by everyone from the coal-huggers to the Greens. Just sample the headings on these press releases:

Josh Frydenberg: “AEMO Backs Turnbull Government’s Energy Plan.”

His opposition counterpart Mark Butler: “AEMO Integrated System Plan Backs Labor’s Energy Vision.”

The Greens’ Adam Bandt: “AEMO Report Shows Only 6 Coal-fired Power Stations Will Be Left.”

Ms Zibelman clearly has a talent for politics. If she ever gets bored with the AEMO, perhaps she should move into politics herself and become our peacemaker. But then, she’s American, and there is that small problem of section 44(i).

If Zibelman is a diplomat, Rod Sims is the tough cop on the beat. The chair of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission probably has the biggest workload of any job in Australia, as the frontline executive making decisions on a wide range of corporate policy issues, crimes and misdemeanours on many fronts. The job of governor of the Reserve Bank is a breeze by contrast.

It’s a good thing that Sims has a deep-seated faith in markets, because a lot of us lose that faith when confronted with evidence of failure as serious as that of our National Electricity Market. Sims has not lost faith: his 398-page report is a searing analysis of why the market failed, but also offers fifty-six recommendations on how it can be put right.

Its assessment of what went wrong is not novel: that ground has been well-tracked already. But the ACCC does a thorough job of marshalling the evidence — although it fails to ask why it is that the NEM, dominated by privatised firms competing in an elaborate market, has done so much worse by its customers than the government monopoly that both sides of politics have preserved in Western Australia.

The report is dense and full of information and opinions — albeit within significant, self-imposed limitations. A reader can hardly be unimpressed by its thoroughness, its focus on the interests of electricity consumers and, in some areas, the boldness of its proposed reforms.

The ACCC’s own assessment is that those reforms would rapidly and significantly roll back the stratospheric price rises of the past decade, within three years saving the average east coast household between $291 and $419 a year, depending on which state you’re in. For comparison, that’s about the size of the tax cut the government is promising most voters.

Its key recommendations are to:

1. Instil more competition into the oligopoly of electricity generation. Sims doesn’t propose to force the big three — AGL, Origin, and Energy Australia — to divest any of their generators, but he wants to ban them from taking over other generators where they already have 20 per cent of the state market, and to expand the regulators’ powers to tackle market manipulation.

2. Offer a government guarantee for ten years to improve the bankability of “appropriate new generation projects which meet certain criteria”: they must be new players, have some big customers signed up, and be able to provide a reliable product (solar and wind projects must have backup generation, that is).

3. Require government-owned transmission networks to write down the value of their assets, which are seen as excessive, thereby reducing the return the regulator allows them and reducing prices by at least $100 a year. It is not clear why the same obligation was not proposed for the privately owned networks in Victoria and South Australia, where electricity prices have risen fastest of all.

4. Encourage the rollout of “smart meters,” and ensure that the regulatory framework allows consumers to use them to shift their electricity consumption to times when it’s cheap.

5. Abolish subsidies for rooftop solar energy by 2021, on the grounds that retail prices have fallen substantially. We’ll come back to that.

6. Require electricity retailers to adopt a default price to be set by the Australian Energy Regulator (an arm of the ACCC), and then offer consumers discounts from that price alone. They could still compete on price, but consumers would no longer be bamboozled by being offered discounts from an incomprehensible “standing offer.”

Most of the response to the report has focused on its plan for a government guarantee to generators — which, as mentioned earlier, does not specify either coal or “baseload” (twenty-four-hour) generators. Sims himself says he doubts that it will ever be needed. Possibly that’s because the conditions the ACCC sets are so tight that only a small field of applicants could qualify — and then the proposed guarantee of $45–$50 per megawatt hour would not be enough to make it worthwhile.

The default price may be a more significant change, and many of us would welcome it with relief. It comes with other proposals designed to restore to consumers the power to make their own sensible decisions — which is impossible at the moment, because the retailers’ various discounts from so-called standing prices have become an unnavigable labyrinth.

The ACCC is convinced that government-owned power companies, especially in Queensland, have been the main sinners in manipulating the market to push up prices. But that is contradicted by the evidence in our earlier chart, which shows that the biggest price rises since the NEM began in December 1998 have been in Melbourne and Adelaide — in the two states that fully privatised their power networks — while the smallest have been in Perth and Darwin, which are not in the NEM, and where electricity is still supplied by government.

John Quiggin, who has written extensively on environmental economics and privatisation, as well as being a former member of the Climate Change Authority under governments of both sides, has delivered a scathing verdict in the Guardian on the ACCC’s apparent ideological bias. It would be useful for public debate if he could give us a more detailed argument — and if Sims addressed those issues in response.

The ACCC forecasts that if its recommendations are implemented, power prices would fall by roughly 25 per cent. Others are deeply sceptical about this, and about earlier claims by the government’s Energy Security Board that its reform blueprint could cut $400 a year from household power bills. I hope it’s true, but I confess I’m with the sceptics.

One problem is that the report focuses solely on cutting electricity prices. By contrast, the earlier reports by chief scientist Alan Finkel and the Energy Security Board had a broader perspective. They aimed to meet three goals simultaneously: lower electricity prices, greater security of supply, and lower emissions. The ACCC focuses on the first goal, gives a nod to the second, but ignores the third.

Given the government’s destruction of the carbon tax/emissions trading scheme, the little progress Australia has made towards reducing electricity emissions has come mostly from the renewable energy target. It is still the only federal policy driver for lower emissions. Yet the ACCC report, after a one-sided examination of the costs of the scheme but not its benefits, proposes ending the RET nine years early, by 2021 — without any examination of the potential impact.

It also proposes that state governments shift the cost of their solar feed-in tariffs to the state budget so they are paid by taxpayers rather than electricity consumers. But consumers are taxpayers, so what’s the benefit in that?

Its figures imply that the RET subsidy for rooftop solar costs consumers on average $17.50 a year — about 1 per cent of their electricity bill — and that will wind down to very little as we approach the scheme’s end date of 2030. The subsidy is now small, will become tiny, and then will disappear. For consumers, it’s barely noticeable.

But for those installing rooftop solar, it’s a vital incentive. The report quotes a recent estimate by consultants Green Energy Markets that the subsidy in 2020 will pay almost a third of the cost of buying a typical 5 kW rooftop solar power system. Think about that.

If that’s right, then removing the subsidy would lift the effective cost of solar power systems by almost 50 per cent. That is one hell of a cost increase to be proposing in a report that aims to make electricity cheaper. And bear in mind: the highest concentration of solar panels is not where wealthy people live, but in the bush and in the new outer suburbs, where battlers live, and dollars matter.

In an otherwise good report, this is an odd exception: sloppy policy analysis that ignores the impact of its own proposal.

Politically, both reports have been greeted warmly. The main criticism has been of the ACCC report by the Greens and environmentalists. Amid the bipartisan canter towards the National Energy Guarantee, their main concern is that the government’s target for reduced emissions from electricity generation — almost a third of the nation’s emissions — is only 26 per cent by 2030, the same target it has adopted for our total emissions.

That is a surrender in the fight to reach the Paris target. We simply can’t cut emissions significantly in agriculture, and it is relatively expensive to cut them in transport and industry. Electricity is where emissions can be cut meaningfully at low cost. We can close down an old polluting power station like Hazelwood or Liddell and replace it with zero-emissions wind and solar, backed up by batteries, pumped storage and demand response.

When Treasury modelled the emissions trading scheme, it estimated that 60 per cent of the emissions reductions would be in electricity, because that is where it is cheapest to reduce them. Where is the Turnbull government proposing to reduce them instead?

The answer is that it isn’t. It knows it won’t still be in power in 2030 to answer for its actions, so it is upholding our Paris commitment on paper while abandoning it in practice. Its plan B is to hope that other countries do more than they have to, so we can buy the rights to some of their surplus achievements and present them as ours. Every previous government ruled that out.

Australia still generates the biggest greenhouse gas emissions per head of any country outside the Middle East oilfields. Those emissions continue to rise, along with electricity prices. We are being asked to believe that under the NEG, and guided by these reports, both will soon start falling.

That’s a lot to ask us to believe. ●