“The most successful political force in the history of mankind.” Michael Heseltine has expressed the thought in less hyperbolic terms many times over a long career, but his core proposition about Britain’s Conservative Party has never wavered.

The former senior minister, now in his eighty-fifth year, projected his extravagant claim from the conference stage for four decades until the 1990s. A social progressive, Europhile, defence hawk and opponent of racism, his boisterous theatricality in a notorious House of Commons incident in 1979 – wielding the mace as Labour members sang “The Red Flag” – earned him the sobriquet “Tarzan.”

Heseltine also has the distinction of having fallen out with both of Britain’s female prime ministers. He precipitated Margaret Thatcher’s abdication in 1990 by challenging her for the party leadership, having four years earlier resigned from her cabinet while it was in session. Two decades on, his passion for urban renewal earned him advisory roles with David Cameron’s incoming government in 2010, which he kept under Theresa May when she succeeded Cameron as prime minister last year.

He lost his portfolio in early March when he voted against the triggering of Brexit. (“The worst decision we’ve made since the war,” he says.) The prime minister dismissed this giant of the party by proxy. She can afford the imperiousness: by every metric, she is sailing to victory in the general election on 8 June. A win would extend the Conservatives’ seven years in office by five more. Against that background, Heseltine’s apotheosis of the party might repay a second look.

Heseltine argues that conservatism is a flexible creed that combines strength and sensibility. By initiating reform as well as adapting to change, by maintaining a broad cross-sectoral appeal, by championing an enlightened capitalism, by upholding the United Kingdom and leading state institutions, and by facing down adversaries without and within, the party has navigated an epoch of popular democracy and social transformation with its flag – the Union Jack, needless to say – still aloft. In the process, it has outlasted every extreme “ism” the centuries have spewed.

These singular qualities have enabled the party to govern over a longer period than any other “in the history of democracy” (one of Tarzan’s more nuanced variants). The Conservative hegemony could even be on a rising curve. The party has been in office for some part of every decade since the 1830s except 2001–10, and for over half of the twentieth century alone or in coalition, which means the proportion of time it has governed grew from 51 per cent in 1900–45 to 57 per cent in 1945–2015. These are volatile times, but few would bet against the trend continuing well into the 2020s.

True, there is no place in Tarzan’s compelling tale for the party’s dark side: its dense compacts with business and finance, its imperial zealots and bigoted fringes, its reliance on a vicious press to attack its enemies, its ageless effort to conscript patriotism to its advantage. But it is not a debating society. The Tories’ purpose is to rule. Even when periodically ousted by its rivals, the hell of opposition is the crucible of serial renewals and comebacks. In fact, the very keenness of that experience is the twin of the Conservative Party’s hunger for power.

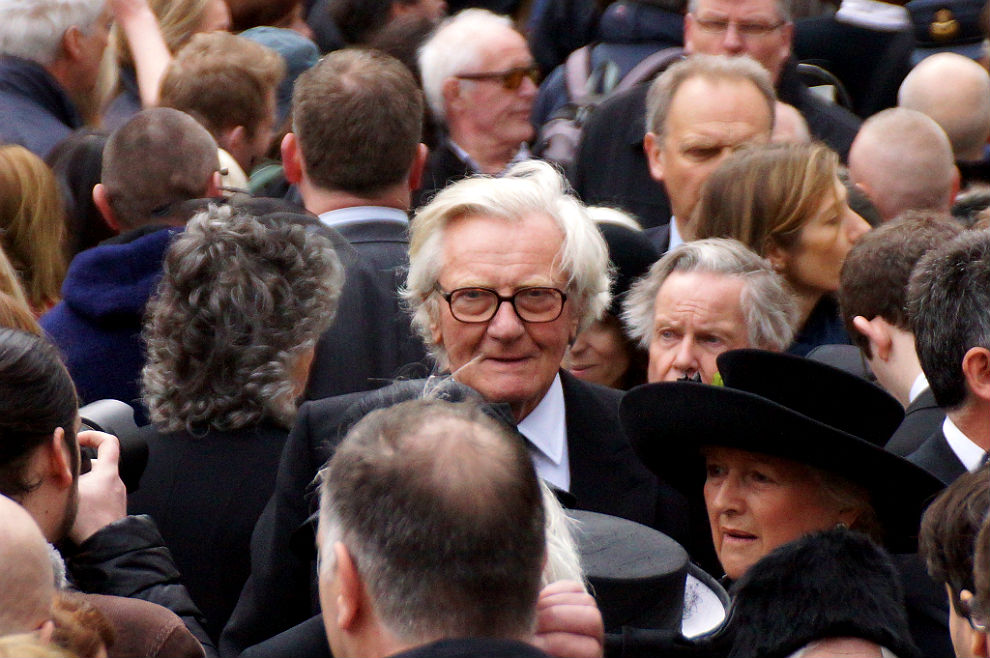

The challenger: Michael Heseltine at Margaret Thatcher’s funeral in 2013. Julian Mason/Flickr

When the far left takes a grip on the Labour Party (as in the 1980s, and again today), that party tends to the precise opposite: a comfort with purifying impotence and an associated disdain of responsibility. It is noteworthy that when these respective structures of feeling were exchanged, before and during the New Labour decade from 1997, the parties’ electoral fortunes moved in step.

This contrast in ethos owes something to the tribes’ respective roots in elements of the gentry and the trade unions, to their evolution as coalitions of interests, classes and ideas, and to contingent events, leadership and political cycles. Without being too deterministic, the historical pattern is consistent. The Conservatives have tended to be lighter on doctrine and stronger on story than Labour; more dedicated to winning, and more ruthless in its pursuit; quicker to adapt to failure, and more impatient with leaders in trouble.

The party’s perennial need is to craft an appeal well enough in tune to make a Conservative government the least-worst option at each election. To the deepest-dyed, such as the lady diner in the upper-crust Savoy Hotel in July 1945 as Labour swept to power, this is the natural order of things: “They’ve elected a Labour government, and the country will never stand for that!” But to intelligent Tories – and the old jibe “the stupid party” is mostly another anachronism – its naturalness could never be taken for granted. “If you do not give the people social reform, they are going to give you social revolution,” the young Conservative Quintin Hogg told parliament in 1943. It was a native version of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s maxim for wise conservatives in every age, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Theresa May’s emergence as leader amid the post-referendum vacuum of June–July 2016 crystallised these differences. A chaotic Tory leadership battle sparked by Cameron’s instant resignation left the then home secretary as the only woman standing (alternatively, “the only adult in the room”). The entire process, with all its momentous implications for the party’s direction and profile, took three weeks. Labour’s transition from Ed Miliband to Jeremy Corbyn had lasted four months and resolved much less.

In many ways, these febrile weeks were the Tarzan account of Conservative regeneration made flesh: face reality, choose, discard, unite, look ahead, reach out, move on. They also followed a profound defeat for the very cause – Britain in Europe – closest to his heart. And they were to reveal Theresa May to be a far more formidable politician than anyone, including her colleagues, had anticipated.

A pattern of discordance between word and action was the least of it. In the battle over EU membership, which ended with a 52–48 per cent decision to leave, May had been a subdued voice for remaining. It was by embracing the winning cause in the aftermath with the customary zeal of the convert – “Brexit means Brexit” was her refrain – that she catapulted to the party leadership and thus to 10 Downing Street. In a landmark speech in late January, she advised her adopted side to be “magnanimous” towards defeated opponents. Weeks later, she cut Tarzan loose, a grating act even amid the then incessant Brexit din. Her unexpected calling of the general election, on 18 April, was another exercise in inconsistency, since she had reiterated over the previous nine months that she had no such plans.

These decisions, however, do make sense as part of May’s two-for-one project to secure her authority and revamp the Conservative Party for another decade. Brexit, a maze-like legal and policy challenge in its own right, has become both an accessory to these other ends and indispensable to their fulfilment.

To put the same point in reverse, May is hitching the 2016 result to a domestic political agenda. That was always inevitable, since the Brexit option was also a pretext for millions of people to express collateral frustrations: with immigration, insecurity, static living standards, or lack of prospects. The vast job of unravelling the UK from the EU would in any case touch every significant policy area, including the now neuralgic relations between the UK’s four constituent nations – or five, if the city-state of London is taken into account. Given this labyrinthine context, May’s “only connect” attitude displays as much strategic nous as cynicism.

May calculates that Brexit is the people’s choice and has to be delivered. Heseltine and fellow big beasts of the political jungle, including former prime ministers John Major and Tony Blair, say it’s not so simple: opinions can change, and parliament must continue to have a decisive role. But for now, May has the power. She wants to use it to bind Brexit into her own comprehensive version of the Conservative future.

The shape of that version was drawn at the launch of the Conservative Party manifesto on 18 May. Significantly, it was held in Halifax, once a centre of west Yorkshire’s textile industry and now a marginal constituency where Labour had a majority of 428 in 2015. A sign of Tory ambition in this campaign is that the prime minister is visiting mainly Labour-held target seats. Two days earlier, Jeremy Corbyn had presented Labour’s manifesto to an excited crowd at Bradford University, six miles away, in the middle of a safe Labour seat, which matches exactly the touring schedule of “the rock star lecturer.”

What Forward, Together: Our Plan for a Stronger Britain and a Prosperous Future lacks in supportive detail it gains in psychic effect, notably in its conscious departure from the deficit-cutting priority of the 2010–16 period and, more generally, from the market-centred thinking of Conservative leaderships since the Thatcher era. True, some policies (limiting the state pension’s beneficent “triple lock,” reordering social care costs, a renewed target for net immigration, a cap on energy prices, notional extra rights for workers) had been trailed, and many others look more declarative than substantive. The real hostages to fortune lie in the we-are-on-your-side language, which champions those “just about managing” and “ordinary, working people,” appeals to “the good that government can do,” and rejects “untrammelled free markets” and “the cult of selfish individualism.”

Caught between alarm and admiration for the chutzpah, sympathetic journalists strain to make sense of this “land grab to the left” by a “magpie politics,” where “Red Tories” might be seeking a “CDU-style party” (referring to Angela Merkel’s power base). Indeed, the document’s lead author and May’s influential adviser, Nick Timothy, is a communitarian who, the Financial Times reported, had consulted with Maurice (Lord) Glasman of the briefly flickering Blue Labour tendency.

Striking too in the document’s presentation was the personalised emphasis on May herself to the extent of almost eclipsing her party. The latter was name-checked but once in her speech. Coupled with the bold venturing of the Conservative campaign into Labour-held territory, the plan is evidently to ease a hoped-for transition across the Labour–Tory chasm. And the closing appeal to “vote for me and my team” ended with another echo of the Churchill speech and poster from 1940 that gave the manifesto its title: “Let us [all] go forward together.” By implication, a vote for May is another vote for the nation’s future at a critical juncture.

The near coincident launch events spiced a thus far desultory campaign, while making even more explicit the parties’ strategic thinking. Planners in the Tory war room, once more including Lynton Crosby, are intent on spotlighting May as a commanding, trustworthy and unifying national leader, almost independent of party affiliation. Labour’s For the Many, Not the Few: A Manifesto for a Better, Fairer Britain, with its promises of greatly increased public spending and nationalisation of the rail, energy, postal and water industries, is less designed for government than to maximise vote share and seats in order to ensure the “left project” can keep control of the party after what’s hoped to be an honourable defeat.

Policy divergences apart, from many angles this election resembles one of the more lopsided episodes in the century-long Tory–Labour feud. The precedent most often cited is 1983, when Margaret Thatcher was still basking in her military victory in the Falklands the year before. She easily defeated the ineffectual Michael Foot, whose problems were accentuated by an unwieldy manifesto dubbed by a party insider as “the longest suicide note in history.” As a result, there is a near universal assumption that the Tories will extend their working majority of twelve in the now dissolved House of Commons (barring acts of WikiLeaks, Putin or Trump, and probably not even then).

May’s profile at the hustings, however, reflects her innate caution. It is ultra-controlled, heavily reliant on repetitious promises and warnings: of “strong and stable” government if her party is re-elected, and of a “coalition of chaos” if it falls short. It also features tight meetings with corralled party supporters, limited and grudging media access, a preference for safer over harder-nosed interview slots, and as much studied vagueness over key policy areas as is feasible.

In the closing stages, more will be required from the prime minister. Since the party manifestos were published, the Conservatives’ substantial opinion-poll lead has narrowed by as much as eight points. That follows criticism particularly over its proposed reforms of social care, which would burden many of the party’s more loyal supporters. Is this the kind of mid-campaign “wobble” that seems to test every favourite in British elections, a sign that voters like winners to sweat for their success, or a hint that the Tory victory is not quite so assured?

One longstanding Labour voter who is thinking the unthinkable adapted a maxim of the English soccer hero turned BBC broadcaster Gary Lineker: “British elections are a simple game. Six hundred and fifty candidates chase votes for seven weeks and at the end, the Tories win.” In truth, the vagaries of the five-nation UK’s fluid electoral geography, with many regional trends and local twists among its 650 constituencies, make it hard to be certain about the precise election outcome. Intriguing polling trends suggest Conservative revivals in Scotland and Wales, the decline of the populist right-wing UKIP, and a lack of Liberal Democrat momentum, which suggest at least a pause in the much-heralded fragmentation of the party system. In turn, however, a bad defeat for Labour will encourage internal ructions that might end in a split. That would be another repeat of the 1980s, which cost the party dearly.

More broadly, the contrast between the election’s surface predictability and the profound uncertainty surrounding the UK’s future could not be greater. Brexit will dominate post-election debate whatever the result. Most voters have reconciled to it, including a substantial body of “re-leavers,” those who voted to remain in the EU but don’t seek to reverse the result.

Insofar as Brexit is salient in the election, Tory strategists see the issue as enhancing the prime minister’s authority to (as she pledges) “negotiate hard” for the “best possible deal” with the European Union. Their desired subliminal memory is of Hilaire Belloc’s poem about a boy eaten by a lion, which ends with a father’s advice: “And always keep ahold of nurse / For fear of finding something worse.” The nurse, in this version, being Theresa May.

The way that relations with the European Union might work to the Conservatives’ benefit was highlighted in the one genuinely arresting moment of the contest thus far. It came on 3 May, when the prime minister – outside 10 Downing Street, having returned from an audience with the queen – lambasted “European politicians and officials” for “issuing threats against Britain” which were “deliberately timed to affect the result of the general election.” Her bullish statement followed the detailed leak of a dinner conversation she and her Brexit minister David Davis had hosted a week earlier, the guests being Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, the EU’s quasi-government, his influential cabinet chief Martin Selmayr, and the EU’s Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier.

In the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung’s account, the Brits came over as under-briefed, ill-prepared and over-optimistic. May was “deluding herself,” living in “another galaxy,” and had to realise that Brexit “could never be a success.”

Tendentious, if at heart accurate: this was the median verdict from insiders. The contempt was also palpable. True, London had minted that coin in its dealings with the EU. Now Juncker, the epitome of Brussels’s back-slapping, job-fixing worst, and Selmayr, the consummate legalist and clever operator, were repaying a fistful. (The smooth Barnier, accountable to the member states rather than the commission, had no part in the leak.) Knowingly or not, and there was elaborate speculation on their intent, it was an irresistible summons to a counterblast.

May’s show of patriotic defiance – “Give me your backing to fight for Britain” – boosted her already high ratings. Her pushback also raised a defensive flutter on the EU side, which really didn’t need to play Goodfellas: it had handed Barnier the brief of squeezing a tough divorce settlement out of the UK before moving to the grit of trade, regulations, security, citizens’ rights, and Ireland’s border. The post-dinner skirmish was at most a revealing distraction. But it allowed May to frame the election while projecting herself as that icon from the national deep: a female warrior in Britannia’s garb.

Her projection had just a touch of that consummate stage actor, Tarzan himself. He will never accept the policy behind it. But the Conservative caravan rolls on, and there will be a place for Michael Heseltine as well as Theresa May at the rendezvous of victory. •