In a week of explosive whistleblower revelations about Cambridge Analytica’s dark partnership with Facebook on behalf of the Trump and Brexit campaigns, a smaller but equally unpleasant campaign scam emerged much closer to home — and this time, on the progressive side of politics.

A meticulous report by Victorian ombudsman Deborah Glass revealed that the Labor Party’s 2014 state election campaign was built on the deliberate manufacture of dodgy timesheets designed to con the taxpayer into paying for a big slice of the party’s electoral fieldwork.

This “artifice” — to use careful ombudspeak — is embarrassing for Labor and expensive as well, given it has had to repay the $388,000 in public funds it misused. It also creates the suspicion that Labor’s adoption of Obama-inspired fieldwork, with its democratising overtones of volunteerism, grassroots engagement and door-to-door voter persuasion, is an improbable and unaffordable fiction.

But the biggest cost to Labor surely comes with the publication of a series of internal emails, training materials and manuals. The documents, acquired by Glass as part of her investigation and published as appendixes to her report, represent a large part of Labor’s campaign know-how — a precious acreage of intellectual property accumulated over more than a decade in Australian elections, incorporating sophisticated practices modelled on US Democratic Party fieldwork.

Those responsible for the artifice — including former Victorian state secretary Noah Carroll, now Labor’s national secretary — might well conclude that their clever funding idea ended up draining the party of precious funds and damaging its reputation and campaign competitiveness. The Liberals’ Victorian president Michael Kroger and, across the border, Australian Conservatives leader Cory Bernardi, both of whom admire and want to emulate Labor’s fieldwork structures, now have an unexpected treasure trove of new information about Labor’s techniques.

For sheer scale and intrusive intent, Cambridge Analytica’s scraping and deployment of fifty million Facebook accounts amounts to one of the biggest dirty tricks in electoral history. It was only exposed thanks to a remarkable combination of very contemporary and extra-systemic events.

There was the courageous, if somewhat shame-faced, whistleblower Christopher Wylie, one of the co-founders of CA. There was the even more courageous and dogged investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr of the Observer in London, working in a now familiar model of cross-border journalism with the New York Times. And there was the covert news camera footage that brought to light more stunning claims about CA’s electoral work by a too-smart-by-half CEO Alexander Nix, now forced out of the company.

By contrast, the Victorian Labor scam was exposed by some reassuringly old-fashioned methods: a parliamentary reference to an ombudsman, whose investigators followed the paper trail and asked precise questions in formal interviews.

It is a simple tale that began with a job advertisement. In November 2013, a full twelve months before the next Victorian election, the assistant state secretary of the Labor Party, Stephen O’Donnell, sent an email advertising for “outgoing, passionate, hardworking people” to work as field organisers and regional field directors on Labor’s campaign.

The job, O’Donnell said, could be very stressful and “isn’t remotely glamorous.” It would require long hours, starting off with a forty-hour week and ramping up to a seven-day-a-week push in the final month of the campaign.

On 19 December, after shortlists, tests and interviews, some two dozen applicants were selected and received an offer of employment from then state secretary Noah Carroll. Carroll informed them they would be appointed to a “full-time fixed-term position” from early March up until election day on 29 November, “with terms and conditions provided in the ALP (Victorian Branch) Staff Enterprise Agreement.” The pay for the nine months was around $47,400 plus 9 per cent super.

But when the new organisers turned up at Labor’s office in Melbourne for their first training session in March 2014, they got some unexpected news. The then opposition leader in the Legislative Council, John Lenders, told them they would also be employed as casual electorate officers by the Parliament of Victoria.

As Deborah Glass notes drily in her report, “This was the first time the Field organisers had been made aware of this arrangement… Reactions to the announcement varied from acceptance to disquiet.”

The novel arrangement reflected some urgent behind-the-scenes scurrying about as Labor, having offered the full-time positions, worked out how to pay for them. Lenders and Carroll came up with the 60–40 solution, whereby Labor would pay 60 per cent of the salary costs while the Parliament of Victoria would pay 40 per cent. In effect, the field organisers were to be paid for two days’ work per week as electorate officers employed by a member of parliament.

And so, in that first week of training in March 2014, Labor’s field organisers were handed, along with their Labor-branded red hoodies and t-shirts, some “folders of partially completed timesheets” stating they would be spending Wednesdays and Thursdays working as electorate officers. They were asked to sign the timesheets but leave the date blank. The sections requiring the name and signature of the MP were also left blank.

As Glass observes, “The roles of a field organiser employed by a political party and an electorate officer employed by the parliament are plainly different.” But because there is a notional overlap — both roles would be able to perform “research and community engagement” — the 60–40 scheme could have been legitimate if, on those two days a week, the employees were being clearly instructed in electorate work by their MP employer. Glass found:

For at least eighteen field organisers who were paid as casual electorate officers, this separation of roles did not happen in practice… During 2014, most participating MPs had limited contact with the persons they had nominated as their electorate officers, and neither these members nor their staff directed their day-to-day work activities.

These artificial arrangements turned on a tap of parliamentary money that would contribute $387,842 to Labor’s campaign in the lead-up to the 2014 election. It also created a parliamentary paper trail that Glass and her investigators were able to track with certainty.

As scams go, it was nowhere as racy as Cambridge Analytica’s Facebook grab. It was populated by an all-too familiar cast of actors: the villain (a scheming head office), the enablers (compliant blind-eye-turning MPs), the weapon (a sheaf of blank timesheets), the dummies (eager young activists). And, of course, the prize: a bucket of public money.

One thing we do know about political parties is that the provision of public funding, far from allowing them to clean up their act, has typically opened them up to more temptations, more irresistible sources of funding for their insatiable campaigning.

But what is novel and intriguing about this particular arrangement is the entanglement of the field organiser role. Over the last ten years or so, the field organiser has emerged as a major actor in Australia’s electoral landscape. Field organisers operate at the heart of the so-called Obama model of election campaigning, which employs data and volunteers to target persuadable voters.

The Obama model required hundreds of thousands, and eventually millions, of volunteers to canvass voters in battleground states — voters who had been individually targeted through sophisticated data analysis. The volunteers’ job was to find those people, knock on their door or call them on their phone, and engage them in “persuasive conversation” on behalf of the Obama campaign. This practice of conversations-based, volunteer-led fieldwork draws in turn on older left traditions of community organising, trade union organising and civil rights activism.

Under the Obama model, it is not the candidate and not the volunteers who make it all work, it’s the field organisers. One of the abiding paradoxes of organisational theory is that grassroots volunteers need centralised managers; collectives produce leaders; flat organisations generate hierarchy to provide coordination and direction. In a fieldwork organisation, the field organisers are the invisible link people in the middle. They recruit, train, and performance-measure the grassroots volunteers and are, in turn, managed by a regional field director.

Labor has steadily been importing this fieldwork model into Australia since 2010 — earlier, if you count the ACTU’s influential 2007 “Your Rights at Work” campaign. After the defeat of Kevin Rudd’s Labor government by Tony Abbott in 2013 — in which Labor’s fieldwork was credited with staunching the flow of votes away from the party — Victorian Labor immediately began focusing on the next state election, due in November 2014. It planned to use fieldwork to help opposition leader Daniel Andrews knock over the Liberals’ hapless Baillieu–Napthine government.

The vehicle for this campaign would be the Community Action Network, or CAN, a grassroots volunteer movement that would bring fieldwork to the marginal seats of suburban and regional Victoria. Its acronym deliberately evoked Barack Obama’s famous campaign battle cry, “Yes We Can!” while neatly avoiding Labor’s own, tarnished, brand. O’Donnell’s job advertisement was seeking field organisers to staff and operate the CAN.

So what exactly is a field organiser? According to O’Donnell’s job description — one of the many Labor documents now made public — they would be “the face of Victorian Labor in communities across Victoria”:

The primary responsibility of the field organiser is to recruit, manage and train volunteers to organise their communities and neighbourhoods into teams that persuade and motivate voters through making phone calls and doorknocking.

The outgoing, passionate and hardworking field workers would be “part of the most exciting and innovative campaign to happen in a generation.”

According to another important document published by Glass, “Field Organiser Roles and Responsibilities,” field organisers are also responsible for feeding their voter data back into “Campaign Central,” Labor’s database of voter information:

If it’s not in Campaign Central, it doesn’t exist. You may not leave the field until all data generated by your campaign has been entered into Campaign Central.

Field organisers also had to complete a daily “qualitative report” about the campaign, and dial in to a weekly statewide conference call of field organisers. Their performance was further managed, and measured, by their immediate superior, the regional field director, or RFD. They would get “Daily Priorities” emails from RFDs, and respond with daily check-ins. Field organiser performance was measured against targets for the number of volunteers recruited, teams assembled, training sessions and strategic briefings for volunteers.

If this makes fieldwork sound like the tightly managed performance measurement you might see in a major corporation, it is. KPIs abound and everyone is held to account: RFDs manage field organisers, and field organisers manage volunteers.

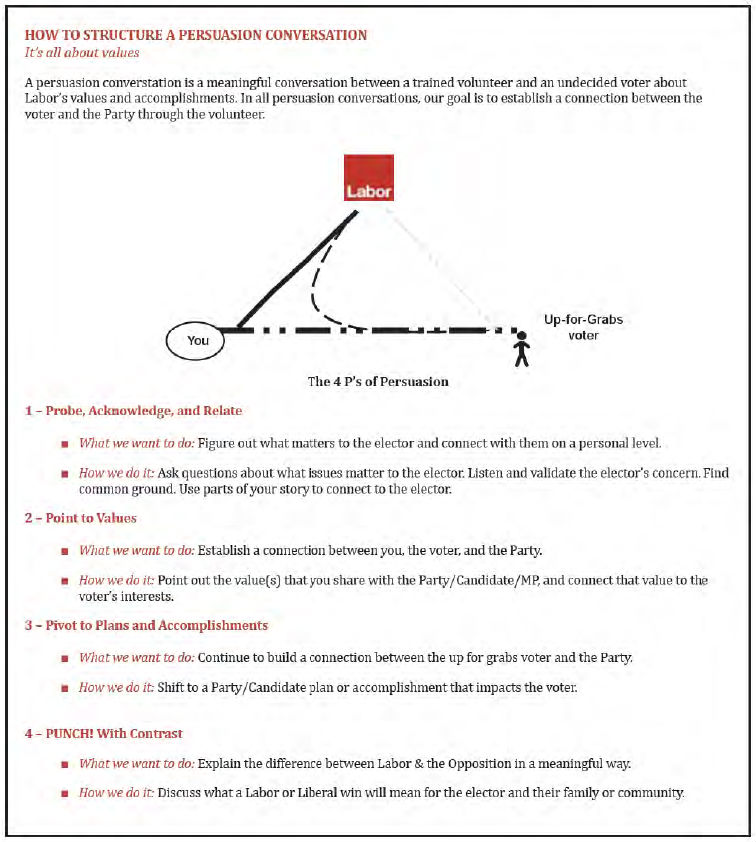

Despite CAN’s participatory public face, the internal documents make it clear to field organisers that this network is in reality “a vertical structure that communicates with a clear chain of command.” Nothing is left to chance. At the pointy end of the fieldwork effort, for example, is the conversation between a volunteer and a voter. After all the data analysis, targeting, training and outreach, what is actually said when a volunteer talks to a voter on the doorstep or phone call? Here’s the Labor chart reproduced in the ombudsman’s report:

As Glass puts it:

A persuasion conversation is a meaningful conversation between a trained volunteer and an undecided voter about Labor’s values and accomplishments. In all persuasion conversations, our goal is to establish a connection between the Party and the voter through the volunteer.

So here’s the script, the “4 Ps of Persuasion”: probe (work out what matters to the voter), point to values (establish a connection with the Party), pivot (to Labor’s plans and accomplishments) and punch (to highlight differences between Labor and the Liberals).

Volunteers are encouraged to draw on their lived experience as Labor activists to persuade voters. “Use parts of your story to connect to the voter,” the script urges.

In this, Labor’s debt to the intellectual guru of US fieldwork, activist organiser-turned-Harvard academic Marshall Ganz, is clear. Ganz developed the training courses in narrative technique that have influenced many Obama fieldworkers and, in turn, Labor’s CAN. According to Ganz, the interlinked stories of “self, us and now” form a powerful catalyst for action to reinforce the committed and to mobilise the undecided — included the undecided voter.

It’s all a long way from Cambridge Analytica’s international swashbuckling, but Labor has shown that when election results are at stake the pitfalls can be hard to avoid. ●

Corrected to refect the fact that the Labor Party has already repaid the $388,000 in parliamentary entitlements used during the 2015 campaign.