Imagining Reality: The Faber Book of Documentary

Edited by Kevin Macdonald and Mark Cousins | Faber | $39.95

The Faber Book of French Cinema

By Charles Drazin | Faber | $45

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition

By Jonathan Rosenbaum | University of Chicago Press | $37.95

WHEN a volume arrives as the Faber Book of whatever it is — cooking, gardening, Icelandic ballads, cinema from here or there — the publisher’s name carries prestige; we expect something finely written, fully informed, up to date. Kevin Macdonald and Mark Cousins’s Imagining Reality: The Faber Book of Documentary, published in 1996, lived up to that promise. It is one of the best books I own on cinema: a wide-ranging array of documents and primary evidence gathered from a whole century, beginning with Maxim Gorky’s report in April 1896, after his first-ever viewing of moving film: “Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows. If you only knew how strange it is to be there...”

In the vast field of evidence Macdonald and Cousins assembled, many documents, and some of the major films discussed, are French. There are nine pages on Claude Lanzmann’s huge canvas on the Holocaust, Shoah (1985), described by the editors as “one of cinema’s greatest achievements.” There are also two substantial interviews with the great ethnographer Jean Rouch (1917–2004), whose inventive documentary essays and occasional excursions in drama (Moi, un Noir) are credited with inspiring the early adventures of the New Wave from 1959 — and those first films by Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol and company were indeed anthropology, pursuing their own Parisian tribes. Breaking out of specialist ethnographic audiences into wider circulation — into the Cinémathèque Française, into the proliferating ciné-clubs — Rouch’s films opened up perspectives: Europe seen from Africa.

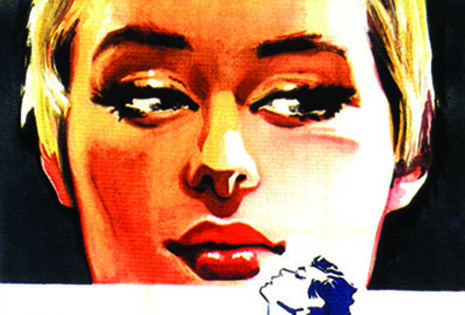

These films were parts of a radically altered framework, in which the Third World could never again be ignored. There, cinema connected with the radical writings of Frantz Fanon, and with the cutting-edge philosophy and journalism of Sartre and Beauvoir, with their journal Les Temps Modernes, from 1945. From the later fifties the critical writings of the young cinéastes, and their early films, harked back to those major intellectual adventures of the postwar years. They also harked forward to the great political and social breaks of 1967 and ’68, and to that moment when Truffaut and Godard closed the curtains at the Cannes film festival. Meanwhile, by 1959, with Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (Breathless), the old, tasteful French cinema of quality, le cinéma du Papa, was decisively out of date. Not that Africa was necessarily visible, or even spoken of, in the works of the New Wave; rather that the privileged France of the bourgeois audience, of de Gaulle in his later reign, was faced with its own unacknowledged levels of injustice and disorder. The way young Antoine Doinel challenges the gaze of the audience at the end of Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) took us all beyond the limits of that particular story; it was a command to look straight at what Beauvoir succinctly named “the lie of the bourgeois life.”

The contrast with Faber’s latest book of cinema, The Faber Book of French Cinema, could hardly be greater. Charles Drazin doesn’t mention Lanzmann or Shoah, and accords Jean Rouch only a single passing reference: serious omissions, not simply because those names should be on anybody’s list, but because they signify a failure to grasp both the range of the field and also the deep divisions within it.

Drazin argues that France has taken cinema seriously — “no other country, from the earliest years of the cinema’s existence to the present day, has done so much to defend the intrinsic worth of an extraordinary medium.” His book is offered as a linear history, and so begins with the famous documents, the Lumière brothers’ pioneering works of the late nineteenth century: the workers leaving the factory, the couple feeding their baby, the train arriving at the station. Then he moves on to Georges Méliès and his almost accidental discoveries of the new invention’s capacity for trickery, magic, the transformations of vaudeville and circus. But although he sees that marvellous plethora of genres at the dawn of cinema, Drazin settles into a simplistic program. He wants to uphold an outdated notion of French cinema as “quality,” in opposition to Hollywood as commerce, and then identifies “cinema” largely with the fictional feature film, the dominant, privileged genre. So, of course, do Margaret and David on the ABC of a Wednesday, and so do the weekend newspaper reviewers; but in a book you’ve got room to do better. Some non-fictional work does make the cut: Marcel Ophüls’s Le Chagrin et la Pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity); Nicolas Philibert’s superb, widely circulated documentary on a small country school, Être et Avoir (To Be and to Have). The great film essayists are nowhere to be seen; Chris Marker is mentioned just once, and none of his films is named.

The book’s most interesting passages are those in which Drazin discusses particular films in their contexts, the conditions of production and distribution. If cinema always lives between art and money, market calculations could never account for France’s output, in the 1920s, of surreal comedy and romantic farce, nor for what followed — the burgeoning through the 1930s, against all commercial sense, of the broad genre known as poetic realism, and above all of the work of Jean Renoir. The best chapter is called “The Spirit of ’36”; there Drazin grasps the short, intense history of the Popular Front, and shows how it framed and empowered five extraordinary films by Renoir: Les Bas-Fonds (The Lower Depths), Le Crime de Monsieur Lange, La Marseillaise, La Grande Illusion and La Vie Est à Nous (Life Is Our Own). The funding was always precarious; the high optimism of that political climate is almost unimaginable — until you see the films. A darker mood prevailed in La Règle du Jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939). Then Renoir fled the war. The films he made in America are not discussed in this book; The Southerner, Swamp Water and The Woman on the Beach might have presented puzzles for Drazin, since he can’t allow Hollywood as “quality.” But right from their beginnings in the fifties, the riders of the New Wave always knew better than that; they knew their gangster movies, as they also knew Jean Rouch.

JONATHAN Rosenbaum’s book, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, gives us a much higher-level reconnaissance, traversing three decades of high-end critical journalism laced with regaling segments of autobiography; the late Susan Sontag’s many ambivalent readers will gain from his account of their exchanges. He was critic for the Chicago Reader for twenty years, and since retiring has written for, and/or attended to, a great range of other publications, including the Parisian Trafic and the Melbourne-based Senses of Cinema and Screening the Past. (In reference to the latter, Ina Bertrand is mis-named as Ina Bernard.) Largely thanks to Adrian Martin, he thinks well of Australian criticism, but (in these pages at least) doesn’t mention a single Australian film or film-maker. But then, in fairness, there’s nothing here of Canada either, little of Asia or Latin America; and this is one of several collections.

The point of the title is that the reception of film is no longer centrally, or even predominantly, an affair of sitting comfortably in the dark as one of an audience before a large screen. That may well be the way many of us still want it, but if cinema pervades our worlds, it’s because of VHS, DVD and computer circulation, the aesthetics of scale and fine detail regardless; this, for Rosenbaum, is the wider domain of cinephilia. Whatever we lose by it, we also gain in access to global cinema and — with luck and the availability of specialist stores and libraries — to the cinema of that other continent, the international past.

The tantalising range of Rosenbaum’s writing in this volume goes from the work everybody knows — or at least knows about — to that which is, undeservedly, hardly known at all: from Chaplin, Monroe, Clint Eastwood and Francis Ford Coppola, for instances, to the films of the Indian and Iranian avant-gardes, obscure experimentalism from many lands including the United States, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoires du Cinéma. Generic boundaries confuse, dissolve and overlap; Rosenbaum quotes, with approval, Abbas Kiarostami’s statement that there’s less of a distinction between documentary and fiction than between a good movie and a bad one. Opening a discussion of Roberto Rossellini’s great film on India (India: Matri Buhmi, or India: Mother Earth), he speaks of “the ambiguous overlaps between documentary and fiction.” So, in Rosenbaum’s generous perspective, that boundary disappears, and Imagining Reality, wonderful book as it is, is in a very special sense out of date. In its pages there’s a brief quote from Chris Marker, in whose work actuality, fiction and political reflection are always inextricably entangled. The editors had asked him, as they asked several others, to comment on his documentary objectives and on the future of documentary. Marker amiably declined to be categorised, but added, “My best wishes for your book: rarely has Reality needed so much to be imagined.” •