The Least Worst Place: How Guantanamo Became the World’s Most Notorious Prison

By Karen Greenberg | Oxford University Press | $49.95

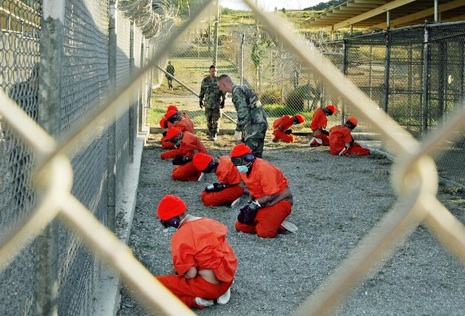

IF ANYONE ever produces a coffee table book called The War on Terror: A Pictorial History – and it wouldn’t surprise me if they do – then there will definitely be some images that no editor could avoid including: the Twin Towers collapsing to earth in a cloud of cement dust and pulverized body parts; Osama bin Laden addressing the world via video in his sinister but elegant Arabic; and the men in the orange jumpsuits.

This last picture shows about ten prisoners – framed by the diamond shape of a wire fence – kneeling in a cage. Each is wearing an orange beanie, earmuffs, a face mask, and handcuffs; covering their hands are what look like oven mitts; over their eyes, blacked-out goggles. Thus deprived of their senses, these men are being stood over by two American servicemen dressed in camouflage fatigues.

The photo was taken at Camp X-Ray, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, on 11 January 2002. The “worst of the worst” – as the Bush administration famously dubbed them - had just arrived at Gitmo. Snapped by a navy photographer, and released by the Pentagon to the media, the photo rapidly entered the public consciousness. To some observers, the image epitomised everything that was wrong with George Bush’s newly minted prison in the Caribbean; in treating suspected terrorists in this manner, they argued, the United States had managed to jettison the very values that made it morally superior to al Qaeda.

The irony, according to Karen Greenberg, is that at the time the photo was taken the human rights of Gitmo’s newly arrived inmates were protected more rigorously than they ever would be again. The photo shows them straight off the plane from Kandahar; it didn’t show how they would be treated over the next few weeks while the detention centre was under the command of a remarkable man.

Greenberg’s book tells the story of the first 100 days of Gitmo’s life as a prison for suspected terrorists. In essence, it is a morality tale in which adherence to the rule of law is pitted against the radical agenda of a national security state convulsed by the events of September 11. But her hero is an unexpected one: Brigadier General Michael Lehnert of the United States Marines.

A career soldier and trained engineer, General Lehnert was given the job of establishing and running a detention centre at Guantanamo. Aided by a force of 2000 marines, in just ninety-six hours he created Camp X-Ray – a functioning prison with cells, guards and medical staff.

But Washington had dropped Lehnert and his Joint Task Force 160 into a policy vacuum. Out of necessity – he had a prison to run after all – Lehnert improvised his own set of rules about how the prisoners would be treated. In the absence of clear orders he fell back instinctively on the Uniform Code of Military Justice, other US laws, and the Geneva Conventions. Told that “Geneva does not apply, but its spirit should be the guide,” Lehnert requested the involvement of the International Committee of the Red Cross, as required by international law. He could never get a straight answer about whether and when Red Cross representatives would arrive.

And then, in what Greenberg identifies as a pivotal moment in the history of Guantanamo, an army lawyer named Colonel Manuel Supervielle became fed up with the lack of legal guidelines and simply picked up the phone and invited the Red Cross to Cuba. Once it was done the Bush administration couldn’t undo it, and Lehnert now had on board an institution that he felt was essential to the proper running of the facility.

A mature and astute manager of men, Lehnart always feared that the situation on the ground at Gitmo could get out of hand. His soldiers were young and patriotic; his inmates were frightened and facing years of legal limbo. When the inevitable occurred and several dozen inmates went on hunger strike after a guard desecrated a copy of the Koran by kicking it, Lehnert faced the biggest crisis of his command. Characteristically, he chose to deal with the problem personally. Many times he sat down with the inmates and talked them through their grievances. He was willing to try anything in order to avoid force-feeding. In the end this disciplined and humane approach prevailed and the hunger strike petered out.

But Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld had other plans for Gitmo. In late February and early March he sent another commander to Cuba: a reservist Major General named Michael Dunlavey. A former US army interrogator in Vietnam, Dunlavey was much more simpatico with the can-do ethos of Secretary Rumsfeld. Dunlavey’s brief was to ramp up the intelligence gathering, never mind the niceties.

By the time Lehnert left Gitmo a few weeks after Dunlavey’s arrival, Camp X-Ray had the Red Cross, a Muslim chaplain, a humane set of rules – including the right for detainees to talk to each other – halal food, and a Koran in every cell. But in short order the Guantanamo of popular imagination – the Gitmo of force-fed hunger strikers, punishment in isolation cells, and the generally unproductive interrogation of prisoners – became the reality.

As narrative, The Least Worst Place reads a bit like a post-Vietnam Hollywood Western. A posse returns with the bad guys and the local sheriff bravely upholds the law and protects them from the mob. But inevitably the humane regime he struggles to construct is undermined by the powers that be, and the Man in the Black Hat is eventually given his badge and takes over. As the hero rides off into the sunset his ears ring with the sound of hammer blows as a gallows is built in the town square.

The Bush administration always intended for Gitmo to become a law-free zone. But at least if General Lehnert’s grandchildren ever ask him, “So, Grandad, what did you do in the so-called War on Terror?” he’ll be able to tell them that he tried to do the right thing. •