Politics makes a very loud noise in the Philippines. Elections are fiercely contested, public debate is endless, and newspapers, radio and television — not to mention ubiquitous social media — carry news, opinion and the inevitable rumours nonstop.

Everything, it seems, is contestable in this political free market. But recent developments suggest that the checks and balances vital to democracy are under threat on multiple fronts, just as the country faces a range of security problems, especially a rising terrorist menace and an unprecedented wave of extrajudicial killings by both police and vigilante gangs in the war on drugs and crime.

The latest attack comes from a familiar source, Rodrigo Duterte. The Philippine president is moving for the impeachment of two of the country’s most powerful independent voices, the chief justice and the ombudsman, in what is being seen as a sustained attack on the country’s institutions of accountability. While opinion polls show that Duterte, elected to the presidency last year, continues to enjoy significant public support, he has become increasingly impatient with criticism and constraints on his power and, Trump-like, furious at attempts to investigate his own affairs.

It doesn’t help that both the chief justice, Maria Lourdes Sereno, and the ombudsman, Conchita Carpio Morales, are women. The president’s difficulties in dealing with women in positions of authority are well-known and deep-seated.

In the Philippines, it is the president who appoints the chief justice from a list of three nominees provided by the Judicial and Bar Council. Importantly, one of the chief justice’s duties is to preside over the Senate in the case of impeachment proceedings against the president. All other impeachment cases are presided over by the Senate president.

Chief Justice Sereno came to the position amid controversy. She was appointed by former president Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino to replace the late Renato Corona, who was removed from office in May 2012 because of his failure to disclose his statement of assets, liabilities and net worth to the public. Corona had been appointed in what Aquino called “a secret midnight swearing-in” a month before outgoing president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s term was due to expire, and just two days after Aquino had won the presidency.

The case against Chief Justice Sereno was originally brought by a lawyer, Lorenzo Gadon, who has said that he wants to avenge slights against former president Arroyo, now a member of the House of Representatives, and the disgraced Justice Corona. Lurking in the background while all this manoeuvring takes place is the family of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, whose widow, Imelda, now eighty-eight, and son Ferdinand Jr (known as Bongbong) are still very active in politics.

According to the executive director of the Institute for Political and Electoral Reform, Ramon Casiple, the move by Gadon, a close associate of Arroyo, is nothing more than a ploy to position Bongbong for the vice-presidency and, by implication, the presidency should Duterte be impeached. The younger Marcos, who ran unsuccessfully for the vice-presidency last year, has an electoral protest against vice-president Leni Robredo currently before the Presidential Electoral Tribunal, which just happens to be chaired by Chief Justice Sereno.

Despite a lack of evidence, the house committee on justice, packed with Duterte supporters, voted 25–2 on 5 October to impeach Sereno, even without discussing point-by-point Gadon’s allegations, which have since been answered in detail by the chief justice.

It was surprising to many that Duterte quickly endorsed the action against Sereno, even calling on her to resign rather than damage the court in any impeachment process. Duterte has also sought to discredit her by publicising the fees she earned as a lawyer, her supposed lavish lifestyle and alleged but unspecified corruption.

Hailed as a human rights champion and fearless defender of the judiciary, Sereno continues to attend to her duties and maintain a hectic public-speaking schedule. After she presented the closing address to the Philippine Economic Society a few days ago in Manila, she was mobbed, especially by younger attendees jostling to take selfies with her.

For her part, ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales’s crime seems to be her resolve to investigate the president. Duterte has accused her of conspiracy and using falsified documents relating to alleged undeclared assets, and says that the grounds for her impeachment would be what he calls selective justice. He promised to present his real bank records at any impeachment trial against Morales to prove that her office held falsified documents. He also initiated an investigation of the ombudsman’s office.

Undeterred, Morales said she would continue her investigation. “The office has already stated its position — to abide by its constitutional duty. No need to add more,” she said when asked to respond to Duterte’s latest statements.

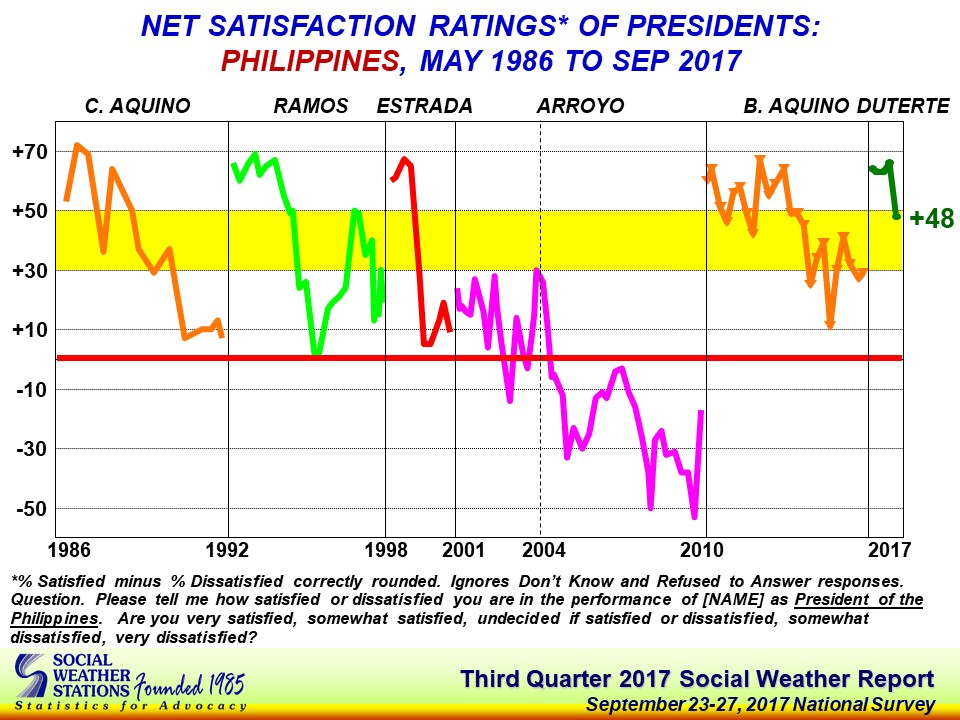

Despite the storms swirling around Duterte — and his ominous references to the need for “revolutionary government,” which horrify the business community — he remains highly popular with men and women alike, according to the latest quarterly survey by Manila-based pollster Social Weather Stations. The survey, conducted 23–27 September, found 67 per cent of adult Filipinos satisfied, 14 per cent undecided, and 19 per cent dissatisfied with the president’s performance, with overall satisfaction having fallen by 11 points from 78 per cent.

How Duterte compares: thirty years of findings from Social Weather Stations

Duterte’s popularity among women is especially surprising, given his well-known problems dealing with them. His sister, Jocellyn, described him as a “chauvinist” in a recent interview — “When he sees a woman who fights him, it really gets his ire” — and recited a list of female critics that included his own vice-president, a senator who is now in jail, and the chief justice. All three crossed swords with Duterte after denouncing his brutal war on drugs, which has killed thousands of people since he took office in June 2016.

While campaigning last year, he joked about the gang rape of an Australian missionary who was killed in a prison riot. Speaking to Philippine troops in May, he said he would take responsibility for any rapes they might commit. But women’s rights advocates also praise him for distributing free contraceptives in his hometown, Davao City, where he was mayor for twenty-two years, and for championing a reproductive health bill opposed by the country’s influential Catholic Church.

In what is playing out in some respects as a Southeast Asian version of the daily crisis that is Washington under Donald Trump, Philippine democracy is once again being sorely tested not just by a president who resents and resists accountability, but also by the ceaseless, self-serving dynastic power struggles that have characterised Philippines politics for decades.

It is still in many respects a working democracy, with an admirably robust media, but its crucial institutions are looking increasingly fragile under the populist assault waged by Duterte. Just where all this will go is anybody’s guess, but the immediate future is, to put it mildly, very uncertain. ⦁