Secret: The Making of Australia’s Security State

By Brian Toohey | Melbourne University Press | $39.99 | 277 pages

“Does Mr Toohey on his own now represent some kind of threat to national security?” When this question was put to prime minister Bob Hawke in May 1983, it hinted at the battle raging between Brian Toohey, one of Australia’s most formidable national security reporters, and the government. That battle would play out in the courts, in the pages of the National Times, in ASIO’s decision to bug Toohey’s family home, and in the journalist’s books.

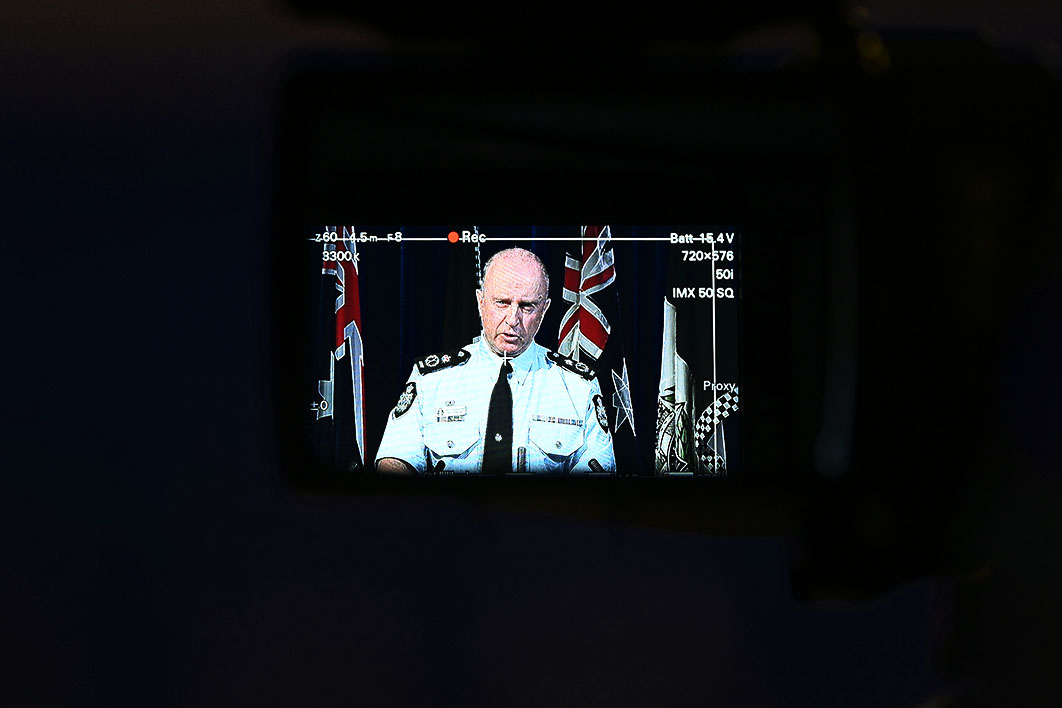

The question “does journalism pose a threat to national security?” (and, for that matter, does Brian Toohey?) has fresh significance in 2019. The tally of federal laws enacted under the banner of counterterrorism has hit eighty-two, many of them granting expansive covert powers to government agencies and criminalising the communication and even handling of government secrets. Exposés of alleged war crimes by Australian soldiers in Afghanistan and potential new surveillance powers for the Australian Signals Directorate resulted in June raids on the ABC’s headquarters and the home of News Corp journalist Annika Smethurst. Prosecutions of whistleblowers are under way and the government hasn’t ruled out charging Smethurst and others with receiving, let alone communicating, leaked government documents.

Meanwhile, we await the outcome of two parliamentary inquiries into the impact of national security laws on press freedom. Before those inquiries commenced, government representatives emphasised that the uniquely broad laws under scrutiny were both necessary and appropriate, and that journalists can’t be trusted to assess the risks to national security associated with seemingly innocuous classified information.

Secret is a well-timed counterpunch for openness, accountability and public interest journalism. The stories that unfold in its sixty short chapters are anything but innocuous, lifting the lid on professional misconduct, personal vices, intelligence bungles, and more.

Drawing on almost fifty years of interviews, leaks and archival research, Toohey delivers a grippingly detailed account of the uses and abuses of secrecy by government agencies. He demonstrates the importance of not assuming that everything is hunky-dory behind the veil of secrecy, and highlights the very real risks associated with failing to question covert intelligence and its practitioners. One result is a disturbing picture of Australia’s imbalanced relationship with the United States, which — far from protecting our national interests — has undermined our independence, drawn us into unnecessary conflicts and cost countless lives.

Toohey writes about Pine Gap and nuclear testing and calls out the government’s ingrained and reflexive fear of Asia. He is persuasively scathing about our spy agencies and laments their unwarranted faith in intelligence information. Indeed, one of the simplest but most powerful messages in Secret is that classified information is often wrong and, moreover, may be politically driven. Take, as obvious examples, the US administration’s assertion that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, or claims that “yellow rain” in Laos and Cambodia was caused by communist regimes’ use of chemical weapons. (The real culprit? Bee pollen.)

Toohey demonstrates the fundamental importance of well-researched public interest journalism in the national security field. Leaks and confidential sources are the bread and butter of Toohey’s trade and it is the coupling of this first-hand information with comprehensive archival research that sets Secret apart. But could this be a dying art?

Last year, the government expanded its secrecy offences so that current or former Commonwealth officers communicating information obtained by virtue of their position — information judged likely to harm Australia’s interests — now face imprisonment for seven years. If the information is security classified or the person held a security classification, then an “aggravated offence” provides for ten years’ imprisonment.

It is also an offence for anyone to communicate information obtained from a Commonwealth public servant that is classified or that damages national security. If prosecuted, a journalist could try to mount a “news reporting defence” by proving that he or she dealt with the information as a journalist and reasonably believed the communication to be in the public interest — a provision that encompasses, of course, national security and the integrity of government information as well as democratic accountability.

These laws have compounded the chilling effect on public interest journalism that was already evident, particularly in the national security sphere. New laws introduced in 2014, for instance, imposed a jail term of five to ten years on, as Toohey describes it, “anyone who revealed anything about what ASIO designates a Special Intelligence Operation.” Despite the fact that “numerous official inquiries and media reports in Australia and overseas have shown that highly secretive bodies will abuse their powers in the absence of strong checks and balances,” writes Toohey, the laws empower intelligence agents to commit criminal acts short of serious violent offences. But, as he astutely observes, “the prohibition on revealing almost anything about these operations still covers murder and other crimes, as well as endemic incompetence or dangerous bungling.”

These few examples demonstrate the great lengths to which successive federal governments have gone to ensure secrecy at the expense of the accountability mechanisms that, not so long ago, were taken for granted. As the only liberal democracy lacking a national bill or charter of human rights, our rights to privacy, free speech, a fair trial and humane treatment are at particular risk. This is what makes Toohey’s story of an ever-expanding, ever-more-secretive security state so disturbing. While the complex network of eighty-two laws (and counting) overwhelmingly operates to expand government power, protections against misconduct and overreach tend to be internally focused, inadequate or simply absent.

Agencies can gain access to retained metadata without a warrant. Gag laws are built into preventative detention orders and a range of ASIO powers. Dual citizens can “automatically” lose their Australian citizenship (a provision recently eviscerated by the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor as unnecessary, unjustified and counterproductive to intelligence efforts). Secrecy offences could criminalise even passive receipt of national security information. Twenty-seven new espionage offences are based on a definition of national security that encompasses all of Australia’s political and economic relations. Workers across the telecommunications industry can be forcibly and covertly co-opted to install spyware and decryption capacities on our devices. ASIO can secretly and forcibly interrogate and detain individuals without charge, and it is a criminal offence for the person being interrogated to tell anyone anything about it. The list goes on.

If, as the New York Times claimed, “Australia may well be the world’s most secretive democracy,” does that also make us the safest? Is Brian Toohey’s book the real threat to national security, based as it is on leaked information, government informants, and assertions that our close relationship with the United States is misguided and potentially dangerous?

It’s hard to believe the answer could be yes. In Toohey’s words, “Australian media reporting has never resulted in the death of an intelligence operative or undercover police officer — far more people have been wrongly killed as a result of intelligence operations being kept secret. Based on erroneous intelligence, drones and special forces repeatedly kill people, including children, around the globe.”

If nothing else, Secret demonstrates the power of national security journalism, reminds us of our democratic responsibility to hold the government to account, and should prompt us to seek more information when presented with claims of secrecy in the name of national security. •