IN recent times the Liberal frontbencher Sophie Mirabella has been at the centre of a media controversy over her former lover’s multimillion-dollar estate. Mirabella – then Sophie Panopoulos – formed a relationship with Colin Howard, a former professor of law who was roughly forty years her senior, in the mid 1990s. They lived together in an inner suburb of Melbourne for about five years.

Howard made a new will in 1997, naming Mirabella as sole executor and beneficiary, notwithstanding the fact that he had two adult children. Three years later Mirabella moved to the central Victorian town of Wangaratta, set up shop as a barrister, got to know the locals, and laid the groundwork for her political career. In 2006 she married former army reserve officer Greg Mirabella.

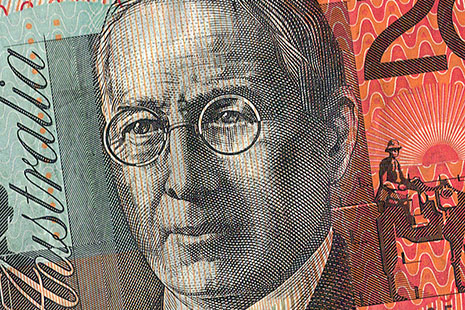

Howard didn’t change his will, and remained close to Mirabella. He even moved to Wangaratta to live on an adjoining property. And when he died last year, aged eighty-three, Mirabella was granted probate for his estate – which included a terrace house in Carlton, an upmarket inner suburb of Melbourne.

At the heart of the media controversy was the profound tension that exists between testamentary freedom and family provision in Australian inheritance law – and the differences between what the law allows and how Australians choose to distribute their estates.

ACCORDING to the principle of testamentary freedom, inheritance is a personal decision. You alone decide what happens to your estate. You can leave it to your spouse, or your lover, or your first-born son, or your children in equal parts, or your grandchildren, or your favourite charity, or your pet Pomeranian.

The principle of family provision couldn’t be more different. It sees inheritance as a family decision: you are the custodian of your family estate, which includes the wealth of earlier generations – and perhaps the wealth produced by your deceased spouse as well. You have a responsibility to deliver it to the next generation as your forebears delivered it to you.

On the face of it, testamentary freedom seems to be aligned with the zeitgeist. It fits in neatly with Mirabella’s libertarian political philosophy and with the individualism that these days crosses party lines. It’s all about choice. Our lives are the sum of our individual choices and this means that we are in charge of our destiny – right to the end.

Family provision, on the other hand, appears more attuned to an earlier sensibility, and the legislation that supports it in Australia dates from the early twentieth century. Family provision underpins the transmission of wealth inequalities from one generation to the next – as Gina Rinehart and James Packer know so well – but it also protects vulnerable family members, notably spouses and children. It allows a court to vary the provisions of a will if it judges that family members haven’t been adequately provided for.

A recent survey of probate records lodged in the state of Victoria during 2006 provides a detailed insight into will-making in twenty-first-century Australia, and shows how the tension between the two models plays out in the wills that Australians actually make. The survey found that when we write our wills we tend to follow three main principles.

The first principle applies to “first estates” – estates where there is a surviving spouse. Here the spouse pretty much gets the lot. The survey shows that in more than four out of every five cases the estate goes mainly to the spouse.

The second principle applies to “final estates” where there is no surviving spouse but there are surviving children. Here, the estate is usually divided equally among the children: in the survey, almost 90 per cent of final estates with surviving children were divided equally.

The third principle applies to final estates where there is neither a surviving spouse nor surviving children. These estates are the most open-ended. Yet even here the survey shows that more than 70 per cent of estates go to family members, mostly nephews, nieces and siblings.

In other words, inheritance is still very much a family affair – a case of family provision rather than testamentary freedom – and follows a straightforward hierarchy. Spouses come first. Children come second, in equal measure. Second-degree family members – nieces, nephews, siblings, cousins, uncles and aunts – come a distant third.

Because women live longer than men, and marry older men, first estates go mostly to wives. (Given the precarious interdependence of old age, it would make a lot more sense if women married younger men. But that’s another story.)

In earlier times, wives didn’t have first call on the estate. Rather, the older principle of “primogeniture” – familiar to readers of early nineteenth-century English novels – meant that it went mainly to first-born sons. In these circumstances, widows often depended on the charity of their children.

This situation survives to some degree in Australia’s intestacy laws, which apply to estates where the deceased did not leave a will. In all states except New South Wales, these laws require that first estates be shared between spouses and children. In other words, they are seriously out of step with how most Australians actually leave their estates.

New South Wales is the only state to have updated its intestacy laws to reflect community attitudes. Since 2010, first estates in that state have gone to spouses in full; presumably the other states will catch up eventually.

Final estates are a bit more complicated. The Victorian survey found that these were overwhelmingly divided equally among children. Increasing longevity means that these children are usually middle-aged, and sometimes elderly – in fact, the average age of child beneficiaries in the Victorian survey was fifty-three, and the oldest was eighty.

Although most Australians leave their estates equally among children, roughly one-in-five exercise their testamentary freedom. Of these, a little less than one-in-ten modify the “rulebook” and leave small bequests to other parties, mostly grandchildren. A little more than one-in-ten break the rulebook and don’t share their estate equally among their children.

Most of that second group favour some children over others or arrange for more complicated distributions among family members. A tiny number skip a generation and give the estate to their grandchildren. And a really, really tiny proportion – 0.02 per cent in the Victorian survey – leave their estate to charity. When it comes to inheritance, children trump charity absolutely.

Finally, consider the most interesting category of all: the estates where there are no surviving children. Most of these final estates go to second-degree family members. But second-degree relatedness is a much weaker claim on inheritance than marriage or parentage. Almost 20 per cent of these estates went to people who were apparently unrelated through kinship, and 6 per cent went to charity.

In the survey sample, the average charitable bequest for someone without children was $62,000; the average bequest for someone with children was $5000. A person without surviving children was at least six times more likely to leave a charitable bequest than a person with children. And a person without surviving children was almost twenty-five times more likely to make a charity his or her primary beneficiary. In the absence of children, charity flourishes.

BUT there is a huge discrepancy between what people give to charity when they’re alive and what they leave to charity through their estates.

In 2004 the Giving Australia Project estimated that the vast majority of Australians, 87 per cent, made a donation in the previous year. Yet an even bigger majority – 94 per cent, according to the survey – make no provision for charity through their estates. Although there’s no reason why people couldn’t leave most of their estate to their family and still make a modest bequest to charity, this is obviously not part of the mental landscape of most Australians.

So inheritance in Australia is overwhelmingly a matter of family provision, with testamentary freedom operating mostly at the margins. But testamentary freedom does empower testators, providing them with an opportunity to exercise personal discretion, and take into account individual and family circumstances. People might, for example, leave small bequests to grandchildren as a token of their affection. Or, when they’re still alive, they might distribute pre-inheritance funds to one child and take this into account when they divide up the estate.

Testamentary freedom also provides leverage. It means that no family members can take their inheritance for granted; they must remain alert to family obligations right up until the end. It reminds us that family provision and family affection are not ordained by nature.

Even so, most Australians don’t exercise their testamentary freedom. Or perhaps more accurately, most people choose to do the same as each other. They leave their estates to their spouses first, and then to their children in equal measure, and then to second-degree family members.

Sophie Mirabella’s inheritance might be aligned with the zeitgeist, but the zeitgeist does not remotely align with how most Australians actually leave their estates. •

• For a fuller discussion of the survey results, see Christopher Baker and Michael Gilding, “Inheritance in Australia: Family and Charitable Distributions from Personal Estates” in the Australian Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2011.

This article has been modified to correct two factual errors in relation to Dr Colin Howard’s will. The original version stated: "For the past twelve months the Liberal frontbencher Sophie Mirabella has been in a legal war over her former lover's estate,” and “Howard's adult children are now challenging the will.” Both statements are incorrect. There has been no legal action in regard to Dr Howard's will. There was no challenge to the validity of the said will, probate was granted and no application was made under the Testator's Family Maintenance provisions. The authors apologise for these errors.