David Campbell: A Life of the Poet

By Jonathan Persse | Australian Scholarly Publishing | $44 | 270 pages

A few months ago I reread David Campbell’s poems of the high country of southeastern Australia and was surprised to find how much they belonged to the old Australia, a place that European settlers struggled to own imaginatively through poetry. “Harry Pearce,” “Winter Stock Route” and many others of his poems claim a timelessness for the pastoral life that Campbell lived and observed so closely, as if sheep and horses had always roamed the Monaro plains in the care of shepherds and bullockies.

Judith Wright’s “Bullocky” and “South of My Days” are better-known attempts to claim a similar relationship to the land for white settlers. By the 1960s, though, Wright had disclaimed her early poems as glorifying a white nationalist vision that she no longer could support.

Like Wright’s early work, Campbell’s poems were the product of the 1940s and 1950s, when war and postwar reconstruction made the Australian countryside seem more precious than ever. His unpretentious lyrics spoke about daily life in the place where you belong: he once commented that “at times I had the sense of riding around my own world of the imagination, my own creation.” Born in 1915, he was the authentic farmer-poet of Australia, though he also self-consciously called on the traditions of the English lyric and the bush ballad, and was influenced by both Robbie Burns and W.B. Yeats. Poems such as “Cocky’s Calendar” and “Works and Days” made the tradition anew for the Australian pastoral in a form that could be enjoyed by any attentive reader.

Jonathan Persse clearly loves Campbell’s lyrics, and his “Life of the Poet” serves more as a celebration of Campbell than as a traditional biography. Persse edited the correspondence of Campbell and Douglas Stewart in Letters Lifted into Poetry (NLA, 2006) and instigated the posthumous publication of Campbell’s war novel Strike by ANU’s Pandanus Press in the same year. He knows the Campbell archives well, and draws on his substantial correspondence for this account of the life.

In person, Campbell matched the ideal of mid-century Australian masculinity to an almost absurd degree. He was tall and strong, with good looks marred by the sporting legacy of a broken nose. The only son of a doctor who owned a range of properties with his brothers, David’s education followed the regular path for squatters’ sons in New South Wales: King’s School, then off to Cambridge University.

At King’s, he was popular and athletic, captain of the school, with no particular academic distinction. At Jesus College, Cambridge, he was an exemplary Australian, elected to all the desirable clubs and winning the presidency of the Wheatsheaf club (devoted to drinking beer) by downing a pint in the quickest time. He won a Cambridge blue for rugby, even playing for England in test matches against Wales and Ireland, and learnt to fly aeroplanes in his free time. Persse includes half a dozen group photographs in which Campbell poses, with the same facial expression, in the uniforms of different clubs and teams. His English tutor, the critic E.M.W. Tillyard, was surprised that he also wrote verse that showed signs of a genuine poetic sensibility.

After war broke out in 1939 he joined the Royal Australian Air Force, winning a Distinguished Flying Cross for guiding his damaged plane and crew back to Port Moresby under fire after a surveillance flight over Rabaul. He was wounded and lost a finger in the attack. By the end of the war, his DFC had a bar.

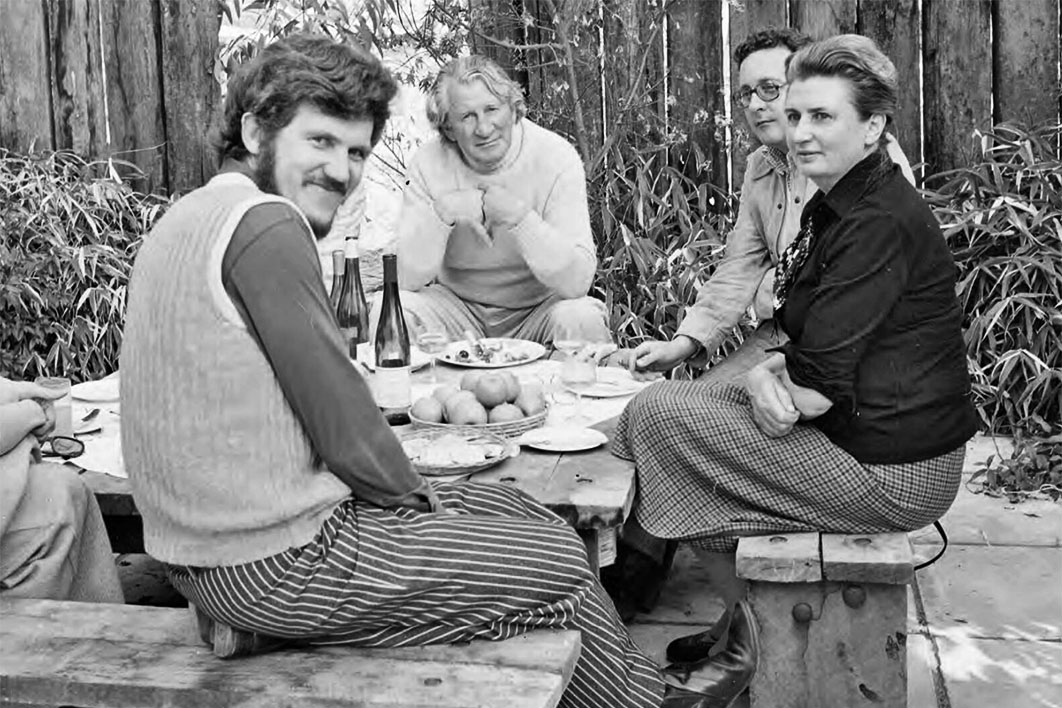

After that glorious wartime career, Campbell settled down to life with his young family on Wells Station, close to the growing city of Canberra. His first book of poetry, Speak with the Sun, was published in 1949, largely on Tillyard’s recommendation, and he gained the friendly support of fellow poet and Bulletin literary editor Douglas Stewart, leading to frequent mutual visits and fishing trips that often inspired poetry. The social life of Canberra, with its burgeoning university and diplomatic corps, meant that Campbell and his wife made many new friends, entertaining them with country hospitality. No longer a solitary farmer-poet, Campbell was increasingly surrounded by other writers and intellectuals, and became well known in literary circles.

This idyllic life began to fall apart when the encroaching Canberra suburbs forced a move to a more remote property outside Bungendore. Campbell began drinking more heavily, with periods spent in Alanbrook psychiatric hospital in Sydney. He separated from his wife and moved back closer to Canberra and the community around the university, including his friend Manning Clark, and developed a relationship with Judy Jones, then a tutor in Clark’s history department. In the last decade of his life, his poetry reflected a new engagement with a wider world, particularly after a visit to Europe with Jones in 1975. His style became freer and often more opaque in its allusions. Though it still drew on Campbell’s family memories, it was just as likely to refer to classical European art.

Persse is reluctant to offer his own readings of Campbell’s work, preferring to quote published criticism or admiring letters from the poet’s friends, but he does provide welcome context for understanding the poems. The publication of Campbell’s selected Poems in 1962 marks the end of one phase of his career, with his later books including responses to and translations of other poets, interpretations of the Aboriginal rock carvings in the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, and even “My Lai,” a protest poem against the Vietnam war. It helps to learn that The Branch of Dodona (1970) includes poems based on his Alanbrook experiences and that Deaths and Pretty Cousins (1975) draws on family history.

In the mid 1970s Campbell embarked on a project with Rosemary Dobson and Natalie Staples to translate a variety of Russian poems into English, and the examples quoted by Persse show Campbell’s lyric facility. By the time of his death in 1979, he was surrounded by admiring younger poets, including Alan Gould and Geoff Page, who were inclined to value his work above the more ambitious poetry of A.D. Hope or Stewart. Yet he was never prolific and favoured the brief lyric over any extended examination of a subject. Clive James (another poet without a single-minded sense of vocation) once called him an “amateur” poet, a description that need not be seen as derogatory in the context of Campbell’s active life.

While Persse sticks firmly to an account of a heroic, admirable poet and Australian, he gives us glimpses of a more complex man: the solitary farmer who made friends easily, the gentle poet ready for a punch-up, the lover of women who seemed to prefer the company of men, the family man who was often unfaithful. He was the guest of honour who arrived late and drunk to dinner at his old school and kicked a schoolmaster to the ground when he made an ignorant comment about Campbell’s poetry.

It is difficult to convey in a biography the sense of humour and fun that made Campbell socially popular, though Persse notes that, even in Alanbrook hospital, he gathered a group of admiring friends. Campbell’s friendships crossed many of the divides in Australia’s literary society. He was a solicitous friend to the suffering Francis Webb, the fishing companion of Manning Clark and a close friend of Leonie Kramer. When Patrick White was writing The Twyborn Affair and wanted to revisit the Adaminaby station where he served as a jackaroo in the 1930s, he called on Campbell to accompany him.

Campbell’s life might be mapped on to a wider Australian social history, with the second world war as a turning point. The consoling quality in the early poetry and the drinking and depression of the 1960s might now be seen as the after-effects of his wartime trauma. Although Persse allows us to see these possibilities, he is more comfortable detailing Campbell’s practical achievements, summarising flight logs and totting up earnings from the sale of cattle, sheep and poetry. He offers only a few sentences on Campbell’s wartime romance and rapid marriage but provides a full account of his divorce settlement. He resists speculating too far beyond the archives.

Anyone who admires Campbell’s poetry will be grateful for this book, and it will provide new readers with an accessible account of the poetry and the man who wrote it. Persse quotes more than seventy of Campbell’s poems, making this an excellent introduction to the work. •