Indonesia’s media is often seen to be among the freest in Southeast Asia. Yet Indonesia’s leading news magazine Tempo last month called on the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission to revoke the licences of the country’s twenty-four-hour news stations, MetroTV and TVOne.

Tempo, a beacon of daring journalism during Indonesia’s authoritarian New Order regime, was banned by President Suharto in 1994. For this consistent advocate of media freedom to call for more stringent government control over the media indicates the depth of the problems revealed during the recent election campaigns. How did it come to this?

In any electoral democracy, media companies often advocate overtly for a particular candidate or party, especially when their own interests are at stake. Australians need look back no further than last September’s federal election, which saw the Murdoch media – spearheaded by the now infamous Sydney Daily Telegraph headline, “Kick This Mob Out” – attacking the Labor government.

What distinguishes Indonesia’s media scene is the fact that the owners of the largest outlets have direct affiliations with political parties and have themselves been presidential candidates. MetroTV is owned by Surya Paloh, chief of the Nasional Democrat Party, and TVOne is owned by Aburizal Bakrie, chief of the Golkar party. Their influence over their outlets dates back to well before Indonesia’s election year. In 2008, as Bakrie and Paloh vied to chair Golkar, both networks flagrantly pushed their owner’s interests, with Bakrie eventually winning out.

Surveys suggest 90 per cent of Indonesians watch television in a given week, with one survey showing four in every five Indonesians “receive information” predominantly from television. With MetroTV and TVOne offering twenty-four-hour news, mainly election coverage, the focus has been on these two stations and their overt bias. But the problem extends more broadly.

My interviews with journalists on a range of publications reveal that ownership considerations cause self-censorship in the newsroom of many of Indonesia’s newspapers. After Aburizal Bakrie purchased the Surabaya Post in 2008, for example, journalists were unable to report critically on his role in the Lapindo mudflow disaster and the lack of compensation to victims. Even the outgoing president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono felt the need to establish his own newspaper. According to its inaugural chief editor, SBY set up Jurnal Nasional in 2006 because he needed a newspaper “which explained the good news as well.” Journalists have become fearful that if they reported critically on stories which involved their owner’s interests, they would be reprimanded, moved to the night editor’s desk or, in extreme cases, fired.

The problem has been exacerbated by the increased concentration of media industry through conglomeration and, more recently, platform convergence, with proprietors who previously only owned one platform (such as print, radio or television) now building large, powerful multiplatform oligopolies.

At the same time, media owners are becoming increasingly involved in politics. Hary Tanoesoedibjo, whose media interests include television stations RCTI, GlobalTV, MNC, Sindonews and OkeZone, first became involved in party politics when he joined Surya Paloh’s NasDem in 2011, before switching to Hanura Party in early 2013. Dahlan Iskan, owner of the powerful JawaPos group – which has over 140 newspapers all around the archipelago – became a minister in SBY’s government in its second term. Chairul Tanjung, owner of TransTV, Trans7 and Detik.com, who had long claimed he wasn’t interested in politics despite suggestions he was close to President SBY, became spokesperson for SBY’s Democratic Party this year, and was soon appointed chief economic minister.

Put simply: Indonesia’s big media is getting bigger in the digital era, and media moguls’ importance has been heightened as their companies dominate the media landscape.

Against that backdrop, media coverage of this year’s legislative and presidential elections was bound to be controversial.

As early as January this year, protesters gathered in front of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission were calling for crackdowns on television stations whose reporting was biased towards their owner’s interests. In the lead-up to the April legislative elections, two television programs broadcast by Hary Tanoesoedibjo’s MNC were pulled off the air by the commission for blatantly pushing Hary’s party, Hanura.

Interestingly, neither of the leading presidential candidates, Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto, owned media companies. Yet Widodo, universally known as Jokowi, still managed to become a media phenomenon. Aburizal Bakrie, Surya Paloh, Dahlan Iskan, Chairul Tanjung and Hary Tanoesoedibjo, meanwhile, performed poorly as presidential or vice-presidential candidates in the opinion polls. This led many to suggest that the old-school elite-media owner was having only a minor effect on politics, and was failing, in particular, to influence the popularity of presidential candidates.

But as Jokowi became a more likely candidate for the presidency – he led all the polls even before he was nominated – media companies with owners linked to political parties toughened up. Their coverage of his media-friendly events thinned out, and in the lead-up to the April elections, politically connected media companies – including MetroTV – began to attack him. In April, Jokowi reportedly met with MetroTV’s Surya Paloh to ask him for fairer treatment.

Once the legislative elections were over, the only question was whether these media companies would support Prabowo or Jokowi. Prabowo enlisted Bakrie and Tanoesoedibjo into his coalition, and each played a prominent role in his campaign. At one campaign event I attended in Jakarta, the two moguls were the only people to address the audience apart from Prabowo, with television cameras from their respective stations fixed on them as they spoke. Together, Prabowo’s TV supporters covered around 40 per cent of the viewing audience, far more than Jokowi supporter MetroTV’s 2 per cent. Partly as a result, Jokowi’s poll numbers plummeted.

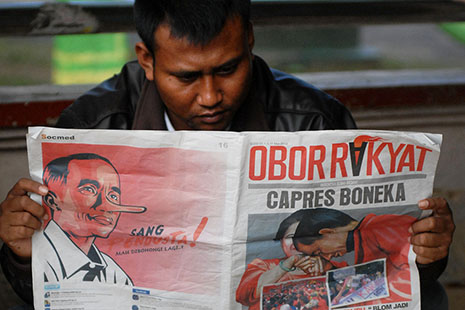

Yet Jokowi did have supporters in the media. Throughout the campaign MetroTV explicitly supported his campaign, following him wherever he went and attacking Prabowo and his Gerindra party. Other media owners allied with Jokowi for different reasons. Jawa Pos Group’s Dahlan Iskan signed up, and paid for the printing of a response to the “black campaigning” of the tabloid newspaper Obor Rakyat, which ran libellous anti-Jokowi material. The response, Pelayan Rakyat, outlined Jokowi’s Islamic credentials and his beliefs and, for good measure, included a picture of Dahlan, Jokowi and his running mate Jusuf Kalla as the Three Musketeers.

The Jakarta Post covered Jokowi positively, running a staunch headline after the first presidential debate, “Jokowi 1, Prabowo 0,” declaring that “the Jokowi–Jusuf Kalla ticket swept all five segments of the live TV debate.” A week before the election, it ran an editorial endorsing Jokowi – the first time it has endorsed a candidate – on the grounds that Prabowo was dangerous for Indonesian democracy. This is all very well, but these statements would have been far more compelling had the newspaper’s owner, Sofyan Wanandi, not been on Jokowi’s campaign team.

James Riady’s Lippo Group, owner of BeritaSatu and the Jakarta Globe, also supported Jokowi’s campaign. So too did Kompas Group, with owner Jacob Utama lobbying Jokowi’s party leader, Megawati Sukarnoputri, to nominate Jokowi for the presidency earlier in the year. No doubt both media organisations believe they supported Jokowi because he promises a brighter future for Indonesia and more closely supports the religious pluralism advocated by both papers, which have ethnic-Chinese Christians as owners. For these organisations, Prabowo’s alliances with hard-line Islamic organisations are of great concern.

So this was a media landscape in which companies clearly supported one candidate or the other – although how, and how professionally, varied enormously. TVOne and MetroTV, for example, felt there was no shame in focusing their coverage on their favoured candidates, while other companies – including TransTV news reports and Kompas newspaper – were far more balanced in their coverage.

The partisan coverage reached its pitch on the night of the presidential election. Among the examples of how media companies rejected the notion of “fair and balanced” journalism, TVOne’s coverage stands out.

The network’s viewers represented 14.1 per cent of audience share – the largest of any television station that evening. For Prabowo to claim victory on the basis of a dubious “quick count” and have that claim supported and encouraged by the network was a new low. This wasn’t just favourable coverage, this was manipulation of the democratic process to confuse voters. The coverage seemed to have been planned long before election night, with guests supporting Prabowo’s claims already in the studio primed for comment.

Prabowo’s victory claims were supported by the Bakrie-owned ANTV, which ranked second with 13.1 per cent of the audience on the night, and Hary Tanosoedibyo’s RCTI, ranked third with an audience share of 12.7 per cent.

MetroTV’s audience share, meanwhile, was 6.9 per cent, making it a poorly placed seventh on election night. The next day, Prabowo refused to be interviewed by network, or by two others sceptical of his victory claim, KompasTV and BeritaSatu TV, alleging that their reporting was “not fair and not just.”

Even the respected magazine, Tempo, whose reporting this year has largely been exemplary, has struggled in recent days to convince many Indonesians that it was indeed fair and balanced. After the election, its journalists placed Jokowi on their shoulders as he crowd-surfed throughout newsroom.

Indonesia is not alone in suffering the effects of concentrated media ownership. There is no easy solution to the problem, but the lack of balance and non-partisan media reporting in this election year should be enough to convince authorities and media-freedom activists that something must be done.

The often-repeated line from media companies – that they should be free to run whatever agenda they like and “let the consumer decide” which media they trust – doesn’t suffice here. It implies that everyone has access to all platforms (Indonesia’s internet penetration is only around 25 per cent), can identify and critique media ownership bias, and have some access to fair and balanced reporting to reduce confusion. That TVOne had the largest audience on election night is further evidence that viewers don’t switch off unreliable reporting.

Would a crackdown by the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission reduce the influence of politically aligned owners? Or would it pressure journalists to report in a way that suits the Indonesian government? Such is the legacy of the old Ministry of Information licensing regime under Suharto’s New Order that many hardened press freedom activists are sceptical of any tightening of controls, especially if various media moguls end up as ministers. Tempo had best be careful what they wish for.

Yet the situation in Indonesia is likely to get worse. In the convergence era, media owners are vying for digital television licenses, internet service providers and communications infrastructure such as satellites and fibre-optic cables. Social media may not be immune to ownership pressures either, as evidenced by Hary Tanoesoedibjo’s investment in WeChat and Bakrie company’s investment in Path, both of which are highly popular in Indonesia.

Unless there are greater thought put into existing media regulations to limit the influence of media owners, the reporting we’ve seen in this election could only be the beginning. •