Two weeks after Tony Abbott called for heads to roll at the ABC, it’s safe to say that the Coalition’s June anti-terror offensive wasn’t a great success. Not electorally, anyway: the polls continued to drift Labor’s way. Coalition MPs are no doubt wondering whether another line of attack, courtesy of the trade union royal commission, will finally undo the opposition’s seemingly intractable lead in the polls.

The first signs of trouble for the government came back in late 2013, just three months after the election and long before the infamous 2014 budget. In the twenty months since then, almost all measures of public opinion have shown the Coalition trailing Labor significantly, though the size and persistence of the gap has often got lost in the commentary about individual polls. Once findings from all the major pollsters are combined, the message is clear: the Coalition has been remarkably unpopular for an unusually long time, and none of its traditional strengths seem to be helping to change that fact.

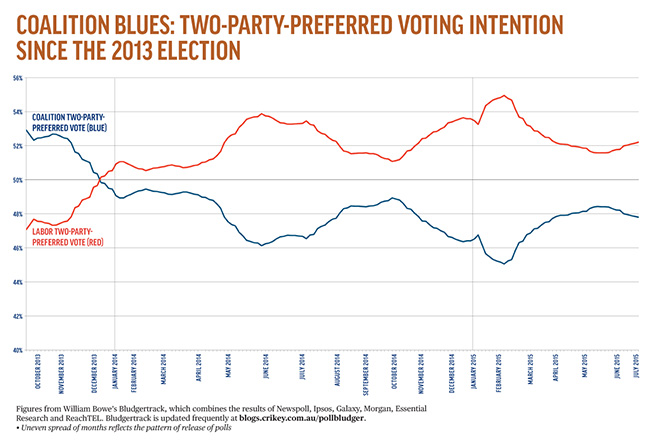

A useful tool for understanding exactly how and why this came about is the aggregated poll data published by William Bowe on his widely read electoral website The Poll Bludger. Bowe takes results from Newspoll, Ipsos, Galaxy, Morgan, Essential Research and ReachTEL, adjusts them for sample size and historical biases, and produces a combined figure, Bludgertrack, which he updates at least weekly. His data for two-party-preferred voting intention, the most useful guide to the parties’ performance, is shown in the chart below.

What’s immediately striking is how soon after the election the government’s first dramatic fall in support began registering. The initial drop, in September 2013, might simply reflect the fact that most pollsters slow down for a few weeks after a change of government, making the overall sample of voters smaller and less reliable. But the relentless decline from late October until mid January, and the failure to recover more than a little of that support at any point since then, are unprecedented among first-term governments, at least since two-party-preferred figures were first published.

It was a messy few months for the new government. Tony Abbott announced that only one woman would sit in cabinet; a small scandal broke out over misuse of ministerial entitlements; Joe Hockey began pushing for a higher debt ceiling; the Senate resisted the mining and carbon tax repeals and opposed new temporary protection visas; and the government reversed its support for the popular Gonski school funding formula. Christopher Pyne can’t take all the credit for the fact that the government dropped behind Labor just three months after the election, but it certainly looks like he put the icing on the cake when he began backing away from Gonski in the last week of November. After Tony Abbott joined in (astonishing everyone by claiming he hadn’t really promised to enact Gonski), the decline continued for another six weeks.

Pulling in the opposite direction – or so the government might have expected – was the launch of Operation Sovereign Borders (eleven days after the election) and Tony Abbott’s declaration that “we stopped the boats in fifty days” (fifty days later). A small lift in the government’s two-party-preferred support in mid October might have been the result, but if the crackdown on boat arrivals had any significant impact on public opinion it was almost entirely counteracted by stiff headwinds.

These and other post-election developments were part of the environment in which the polls turned against the Coalition. But the most plausible reason for its sudden loss of support is that the election result was essentially a rejection of Labor rather than a win for the Coalition and its unusually unpopular leader. (Leaders’ popularity can have unexpected effects, though, as Inside Story contributor Peter Brent has shown.) The Coalition’s strategy since Malcolm Turnbull lost the opposition leadership in 2009 had been almost entirely negative, right down to the fact that Tony Abbott denied he would ditch Gonski and presented himself as a friend of Medicare. Labor’s problems, especially its failure to explain its economic performance (Peter Brent again), decided the election. But popular Labor policies – particularly for education and health, but also for industrial relations, ABC funding and parts of the welfare system – weren’t necessarily part of the mix that lost it government.

By February last year, five months after the change of government, the Coalition had plateaued on a little over 49 per cent of two-party-preferred support. (At the same point in the first Howard government, the figure was around 6 per cent higher.) It stayed there until late March, when the long decline to budget day and beyond set in. The home insulation royal commission had recently resumed and the prime minister had declared victory in the fight against “boats,” but other factors seem to have turned a significant number of survey respondents towards Labor. It might have been Arthur Sinodinos’s decision to step aside from his ministerial post, or the government’s plan to repeal section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, or Tony Abbott’s reintroduction of knights and dames, or even the announcement of a free-trade agreement with Japan, all of which happened in late March and early April.

From early April the government began revealing details of the planned cuts in the 13 May budget, and its poll figures began to drop more quickly. The decline continued after the release of the Commission of Audit report, then slowed slightly after both of the government’s politically motivated royal commissions hit the headlines. But then Joe Hockey’s first budget intervened, confirming fears that the government wanted to reshape Australia in ways that it hadn’t made clear before the election.

The budget furore centred on tax and welfare policies that took resources from lower-income households and from young unemployed people. For voters who’d got sick of Labor but still supported Medicare, government schools or even public transport, there was plenty to dislike. The southward trend continued.

Fairly quickly, cabinet started to offer up sacrifices and fresh enticements. A fortnight after the budget, George Brandis signalled a rethink of the plan to dump section 18C. Four weeks later, after the Islamic State made dramatic gains in Iraq, the government announced its first set of anti-terror laws. Brandis’s announcement came at the beginning of a very modest rise in support; the terror laws had no obvious impact.

What seems to have set the Coalition on a rising trajectory was the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 over Ukraine in mid July. (Though it could also have been the Senate vote to repeal the carbon tax, or the early signs that the government might not proceed with the worst of the budget cuts – or simply a continuation of a gradual drift back from Labor’s high point in May.) A week after the Ukraine attack, Tony Abbott announced that Australian troops would be sent there to protect investigators, and another week later the planned changes to racial vilification laws were dropped and a second set of anti-terror laws released.

The cumulative effect of these developments, and whatever else was in the minds of the pollsters’ sample of voters, was that the government’s two-party-preferred support reached 48.5 per cent in mid August (up from 46.1 per cent at its lowest point). It stayed roughly there until the mining tax was repealed, the report of the home insulation royal commission was released, Julia Gillard appeared at the trade union royal commission and the government increased the terror alert to “high” – four events that coincided with a modest rise of 0.3 per cent for the government over the next couple of weeks.

Then the long slide to Prince Philip’s knighthood began. Tony Abbott’s undertaking to shirtfront Vladimir Putin had no measurable effect on the two-party-preferred figures, and neither did the G20 meeting in Brisbane. A backdown on defence leave, a partial backdown on university funding and a confusing shift on the $7 GP co-payment coincided with the beginning of a brief lift in the poll numbers. Perhaps the prime minister’s candid confession at the beginning of December that it had been a “ragged week” for the government calmed some voters and temporarily stilled growing leadership speculation in the media. A more pronounced, if brief, lift came ten days later, just after the Martin Place siege. But the decline had well and truly resumed by the time Mr Abbott dismayed his colleagues by knighting the Duke of Edinburgh.

At that point a group of Liberal backbenchers finally decided to act. Although their bid to spill leadership positions failed, the government’s poll figures improved. No doubt this was partly a what-goes-down-must-come-up effect, but it also reflected a period of relative quiet in the Coalition’s ranks. The ragged weeks didn’t entirely go away, but the government fairly quickly regained a full percentage point of support and slowly dragged itself up to the level it had reached after its post-budget recovery in August. It was in sight of Labor, but this was nowhere near the bounceback the prime minister would have been hoping for.

Despite the subdued impact of the first set of anti-terror legislation in June last year, Tony Abbott seems to have concluded that fear was his best defence. Yet the announcement of more funding for anti-terror measures, coming just after Joe Hockey’s second budget, produced no measurable advantage. Other poll questions were picking up support for more and tougher anti-terror laws, but that didn’t translate into increased support for the Coalition. In fact, after the government’s focus on security issues intensified in mid May, its poll figures plateaued and then began to fall. Terror laws, terror rhetoric, even the Martin Place siege – none of them had boosted the government’s support in any significant way.

June this year was the month in which the government, according to unnamed Coalition sources, found the measure of Bill Shorten and finally regained its political momentum. The latest combined leadership poll numbers suggest otherwise, with Tony Abbott on a net satisfaction rating of negative 26 per cent, one percentage point lower than Shorten. Two-party-preferred, as the chart shows, the Coalition has been going backwards since the middle of May and had fallen to 47.8 per cent by the middle of last week.

Nor has there been much evidence, so far at least, of shifting the focus of attack from national security to Labor’s links with the unions. Here, the poll figures once again are not encouraging for the Coalition. If the initial hearings of the trade union royal commission last year had any impact on public opinion it was lost in the furore following Joe Hockey’s first budget. In November, when the commission raised doubts about aspects of Julia Gillard’s widely reported testimony (although it cleared her of any criminal activity), columnist Andrew Bolt described the observations as “devastating for former leader Julia Gillard and damaging to current leader, Bill Shorten.” The polls continued their drift towards Labor.

It will be a couple more weeks before it becomes clear whether the opposition leader’s own appearance at the commission brings as little benefit for the Coalition, but it’s worth noting that since revelations about Bill Shorten’s years with the AWU were first published in newspapers last month the polls have moved Labor’s way.

During the period of declining Coalition support that began in early May, Mr Abbott and Mr Hockey expressed views about the housing bubble that contrasted strikingly with observations made by the Coalition-appointed head of Treasury and the governor of the Reserve Bank. Joe Hockey exhorted households and small business to get out and spend, and Tony Abbott continued his war on wind.

What the aggregated poll figures suggest is that the Coalition’s support is unlikely to rise in any significant way, almost regardless of what it does. But unnamed Coalition sources told journalists in June that the prime minister isn’t worried about the poll figures. He believes, they say, that the gap can be closed when the heat is applied to Labor during an election campaign. It’s likely that the media coverage of Bill Shorten’s appearances at the trade union royal commission will have added to that conviction.

Mr Abbott is probably encouraged by the experience of John Howard, who won the 1998 election after a twelve-month run of bad polls. The not-so-encouraging fact is that Mr Howard was still behind on election day – he scraped back into government with less than 49 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote – and could just as easily have lost power. And he had the advantage of campaigning under much more favourable economic conditions.

The Poll Bludger chart doesn’t offer any easy answers for members of the government who don’t share their leader’s confidence in his campaigning skills. What it does show is that one well-received budget and a renewed focus on terrorism hasn’t done the government much good. Of the four main vote-influencing issues – economic management, national security, health and education – the first two haven’t been working the government’s way as they traditionally do. And the other two – well, it’s hard to see many votes in promises of tens of billions in cuts to schools, universities and healthcare.

Unless, of course, the Coalition’s longstanding reputation as the better economic manager proves to be more resilient than it deserves to be. Here, again, the signs aren’t so good for the government. When Essential Research asked respondents whether they thought Australia’s economy was heading in the right direction after this year’s budget, 40 per cent said “no,” 35 per cent said “yes” and 25 per cent said they didn’t know. A week later, responding to the question of who would be the better treasurer, 29 per cent said Joe Hockey, 23 per cent favoured shadow treasurer Chris Bowen and 47 per cent said they didn’t know.

Neither result is a resounding endorsement of the party that voters are reputed to trust most on economic matters, or of a budget that was generally seen as a great success for the government. If it’s still true that governments lose elections rather than oppositions winning them, then this government’s extraordinarily poor performance over most of its life makes its survival beyond the election seem a question of luck. Bill Shorten’s performance at the trade union royal commission is a reminder that Labor might turn the old adage on its head, but it would be reckless to bet on it. •

Many thanks to William Bowe for providing detailed Bludgertrack data.