The Enigmatic Mr Deakin

By Judith Brett | Text Publishing | $49.99 | 490 pp

A declaration, I think, is in order here. I do not much like Alfred Deakin. Some years ago, armed with a modest research grant, I set out to write a study of his political career, but the more I came to know him, the less I liked him.

The man who was widely hailed as “Affable Alfred” was increasingly revealed to me as “Devious Deakin,” a complex, secretive, contradictory man whose self-proclaimed principles became ever more flexible as he — a deeply private person who liked to talk to the dead — swam uncomfortably in the swirling currents of public life.

I did not abandon Deakin altogether: the proposed study became a chapter — “The Strange Political Death of Alfred Deakin” — in a larger book about the departures of all twenty-eight former prime ministers (and one almost prime minister), The Manner of Their Going.

Judith Brett has persevered where I did not, producing what is truly one of the great political biographies of our time, a delicately nuanced, warm and insightful account of — my personal misgivings aside — one of the most noteworthy political figures in Australian history.

A rounded man of voracious intellectual appetite, Deakin stands out as the most unusual — perhaps even the oddest — of our not always distinguished former leaders. Whatever his failings as a leader, and they were many, he was unquestionably the dominant figure in that crucial first decade of the Commonwealth: not just for his three terms as prime minister, but also for his kingmaking, his vision and the stamp he left on government and party politics. On all these points, Brett teases out the telling detail, bringing to vivid life a figure so unlike any other we have known.

Given the complexities and ambiguities of her subject, the task she sets herself is ambitious in the extreme. “I have tried,” she writes, “to give each of the three strands of Deakin’s life its due: his intense inner world, his public life in politics and his family relationships, following the daily, weekly and yearly rhythms, as well as the arc of his life’s physical and psychic energies.” That task is accomplished magnificently.

Her very apposite title is taken from a line penned by none other than her subject — who, as the anonymous Australian correspondent for the London Morning Post, maintained a running political commentary even during his own prime ministerships — when he wrote of the controversial merger of his own Protectionists with their former foes, the Free Traders, the so-called Fusion. “For reasons known only to himself, which are a perpetual subject of controversy in our Press, Mr Deakin pursues his enigmatic methods of action,” he told Post readers in 1909.

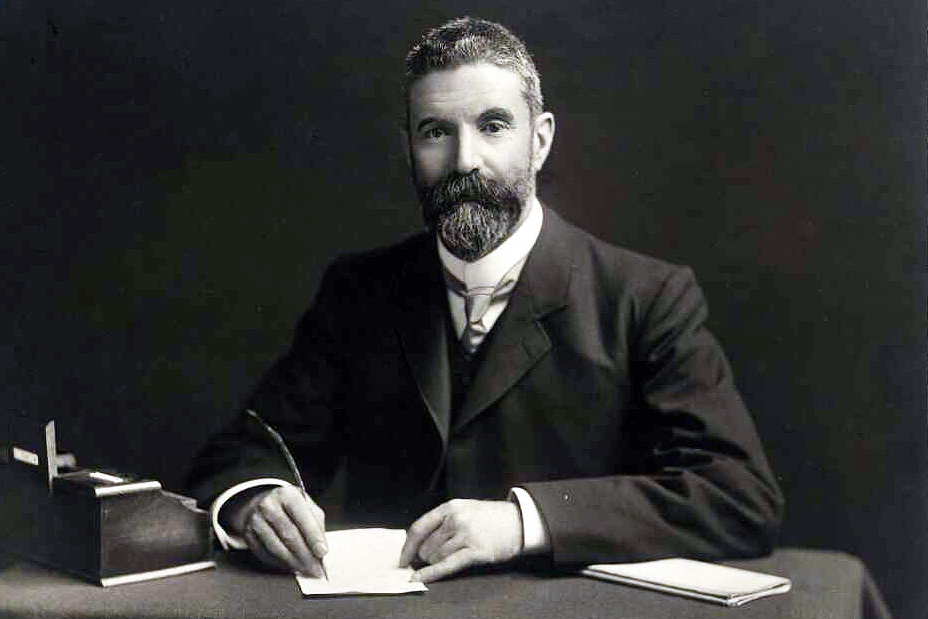

In seeking to locate Deakin in our collective memory, Brett contrasts him with the bushranger Ned Kelly, whose “homemade armour is etched into the national myth by Sidney Nolan’s jaunty silhouette and his crazy bravery…” Deakin (who had, as a journalist, witnessed Kelly’s execution in 1880) “is remembered too, but not so vividly, more as a bearded worthy than a national icon.” He was far removed from the typical Australian of the time, whose thoughts, according to his diary, he often puzzled over.

Deakin was never a mate. He didn’t swear and rarely drank. He didn’t play organised sport nor fight in the Great War, was unfailingly courteous and, although many loved him, he always held himself a little aloof.

Yet the story of Deakin, for all its high-mindedness and selfless dedication to public service, is one of tragedy, both political and personal. We now know, almost a century after his death, that his faculties were in rapid and irreversible decline by the time he retired from politics in 1913. His diaries, from which Brett quotes, offer a poignant account of a man keenly aware of what was happening to him.

For all his undoubted achievements, Alfred Deakin was already politically dead when he walked away from parliament. The party of which he was once the driving force was no more, the social liberalism he had championed so fervently was but a fading ember, derided and left to wither by those who had been bequeathed what remained of his political edifice. Even his much-vaunted belief in principle above expediency appeared hollow and time-worn.

If Deakin the historical figure appears in some ways ambiguous, this is not so much to impose a judgement as it is to acknowledge that he cultivated ambiguity as an essential part of his persona. For example, his official secretary when he was prime minister, Malcolm Shepherd, recorded in his memoirs how members of the public frequently sent him books and articles to read; in return each of them received a deliberately worded reply acknowledging receipt and assuring the sender that Deakin “would lose no time in reading it.”

In his ambiguities, he was often oblivious of the effect he might have on those who took him at his literal word. When his long-time colleague and supporter John Forrest sought his advice about contesting the leadership, Deakin responded by saying that he “approved” of such a course. Forrest was shattered when Deakin voted for Joseph Cook in the ballot and then defended the decision by saying that approval did not necessarily constitute support.

So, too, in his political relations did Deakin display this characteristic ambiguity. In the first decade of the Commonwealth, he was effectively the kingmaker. Occasionally he wore the crown, and when he chose not to wear it, it was he who bestowed it. It was Deakin who paved the way for Chris Watson to lead the first Labor government in 1904 and, when that short-lived administration ran into trouble, it was he who arranged the tactical support from among his own followers for his arch-enemy, the Free Trader George Reid, to take the reins.

It was a typically ambiguous Deakin speech, open to all sorts of interpretation, that brought Reid undone. Deakin argued that it was merely a “friendly warning” but made no attempt to deny journalists’ view that it was a “notice to quit.” He took this brutal step without apparent concern for those of his own supporters whom he had persuaded to join Reid in coalition.

Indeed, the entire political career of Alfred Deakin is neatly bookended by ambiguity. His election to the Victorian parliament in 1879, when he was but twenty-two, was momentous in itself, but not nearly so momentous as the explosive effect of his first speech, in which he announced his resignation owing to irregularities in the poll. Irregular it was, to be sure, but Deakin’s apparent high-mindedness might just as easily have been directed at the entire political climate of the time, about which he wrote in his book The Crisis in Victorian Politics, 1879–1881.

What Deakin didn’t say, though contemporary press reports had plenty to say about it, was that in addition to voting irregularities and rampant sectarianism, vote buying and political blackmail were also prevalent, and in Deakin’s case, voters were threatened with no new railway line if the preferred Liberal candidate (that is, Deakin) were not elected. Even then, before the surprise announcement in his inaugural speech, he had kept his cards to himself. The premier, and Deakin’s own leader, Graham Berry, mildly reproved him after his resignation: “It’s all very well for you. It puts you on a pinnacle. But what of the party if you lose them a seat at this juncture?”

Deakin came back, of course, though not at his first attempt, his apparent distaste for political horse-trading quickly overcome. He went on to spend the next thirty-three years in and out of office in Victoria and the early Commonwealth. In the crucial period in the 1890s, when Deakin devoted much time and energy to the federation cause, his private member status in the Victorian parliament was not without ambiguity. Having held office in a colonial government that presided over rampant speculation followed by a devastating financial collapse, massive bank failures and a depression that brought misery and ruin to many — and Deakin himself was not immune to significant financial loss through injudicious speculation — he managed, unlike many of his erstwhile colleagues, to remain politically solvent, albeit tarnished.

Deakin is best remembered now as the driving force behind the federation movement, a status not wholly unconnected with his having written the standard account of proceedings (though it was not published until 1944, a quarter of a century after his death). Certainly, he played a key, even heroic role. He was the intellectual powerhouse of those first federal governments, which showcased the nascent Australian democracy to the world as a progressive social laboratory extraordinaire, pioneering the secret ballot, universal adult suffrage, an advanced system of social welfare, and compulsory industrial arbitration that not only recognised, but institutionalised, class conflict and provided a means for its adjudication.

Deakin’s retirement in 1913 elicited more critical reflection than praise. The liberal Age saw him as

never framed by nature for what is called a strong man… All his life he has hankered after coalitions and fusions… His recent career has been unfortunate… The Fusion, which was Mr Deakin’s creation, is almost certain to die with him.

The conservative Argus — never supportive of Deakin — observed that in his party associations, his control of parliament and “his conduct of public life,” he was “never really successful — never half so successful as a man with only a fraction of his subtlety but a little more fixity of purpose might have been.” The acerbic Labor MP Frank Anstey published a critical pamphlet about Deakin’s political career, writing that “to be forgotten is the best that can happen to Alfred Deakin”:

No man can stand at his political graveside without being reminded of the pledges he has made — and broken; the parties he has led — and shattered; the friends he has kissed — and betrayed; the principles he has supported — and deserted. He could be faithful to nobody, and towards the end nobody trusted him.

Gazing back through the sepia-tinted lens of receding history, we see an imposing yet remote figure. Unmistakably Victorian in appearance, exuding the sombre confidence of an expansive and seemingly limitless era that crafted its edifices and monuments in solid bluestone, Deakin symbolises an essence of an age now beyond our grasp. In his demeanour is the accumulated self-conscious virtue of that morally uplifting belief in self-improvement and the dawn of the meritocracy, and a sense of unshakeable self-belief and permanence of cherished values and verities that his world believed were eternal.

Yet for all the extravagant and ambitious hopes built on the great liberal project that ushered the infant nation of Australia into the new century, the world of which it was but a tiny part was already marching inexorably to its doom in the horrors unleashed in 1914 and beyond.

Judith Brett’s biography, with its stated aim of bringing Deakin back into Australia’s contemporary political imagination, captures the triumph and tragedy in equal measure — but, even after almost 500 pages, the enigma remains. •