The Photograph and Australia

Showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until 8 June 2015

The Photograph and Australia

Exhibition book edited by Judy Annear | Art Gallery of New South Wales | $70

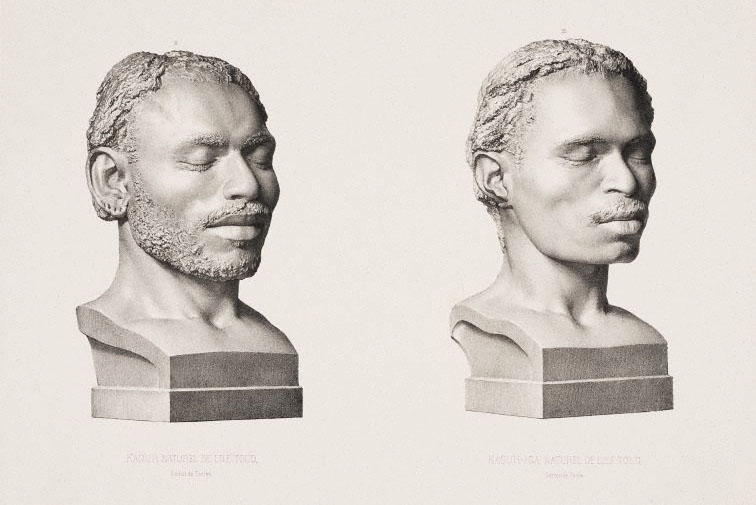

Among the many striking images in this ambitiously titled exhibition, and in the book that accompanies it, is a double portrait, made in 1846, of Kaour & Kaour-Iga Natives of Torres Strait (above). The curious immediacy of the image – the ease with which we can infer the breathing lives of these two men – is difficult to explain. The composition, after all, is flat and lifeless. The men are presented to us as sculpted heads, pieces of classical statuary on plinths, posed against a plain and featureless background. They appear within the same border but are otherwise quite separated from each other and from their own bodies.

The static composition and its clear purpose as an ethnographic document are of a piece with the elaborate and very un-immediate process by which the image came into being. Everything we learn about the creation of this photograph points away from immediacy towards artificiality and distance. In fact it is not, strictly speaking, a photograph at all, but a lithograph based on a daguerreotype made by the French studio photographer Louis-Auguste Bisson and his brother Auguste Rosalie Bisson in the early 1840s.

Louis-Auguste had the adventurous spirit – he famously climbed Mont Blanc, followed by a string of porters charged with carrying his cumbersome photographic equipment – but he didn’t get as far as the Torres Strait. Instead his daguerreotype captures not the men themselves but life-casts produced in the late 1830s by Pierre-Marie Alexandre Dumoutier, a phrenologist who accompanied the French explorer Dumont d’Urville on one of his Pacific voyages. Dumoutier’s moulds were sent back to Paris to be turned into impressions, to be photographed, and to then form the basis of an easily reproducible lithograph.

The image on the gallery wall is thus a lithograph of a daguerreotype of a life-cast, itself an impression from a mould – image built upon image. And yet, despite the many removes between the subjects in the frame and the contemporary viewer, the expressions on the men’s faces convey an individuality that no amount of formality and process can contain. Their eyes are closed but we know they are not asleep. They are thinking and wondering and waiting for it to be over, for the gypsum to be removed so that they can resume their lives. And in this imposed stillness the man on the left, in particular, appears mildly amused at the absurdity of it all.

The curator of this fascinating exhibition, Judy Annear, has divided the display into four main themes – settler and Indigenous relations, exploration, portraiture and transmission. Their breadth belies the extent to which we are led – or nudged perhaps – into drawing all kinds of connections across eras and genres, and into seeing quite disparate photographs in the context of one another. We are also led to question the sharp distinction still routinely made between “documentary” and “art” photography, and to see how these categories can overlap or simply swap places, according to the context in which the image is presented to us – in a scientific database or on a gallery wall, for example – or perhaps just to our mood on the day. The exhibition includes a number of images that were originally made in the interests of scientific documentation but here assume a parallel life as aesthetic objects inviting contemplation. “Hand,” a very early X-ray photograph made in Launceston in 1896 by Frank Styant Browne, demonstrates the way in which photography could not only document the visible but also show what was previously unseen.

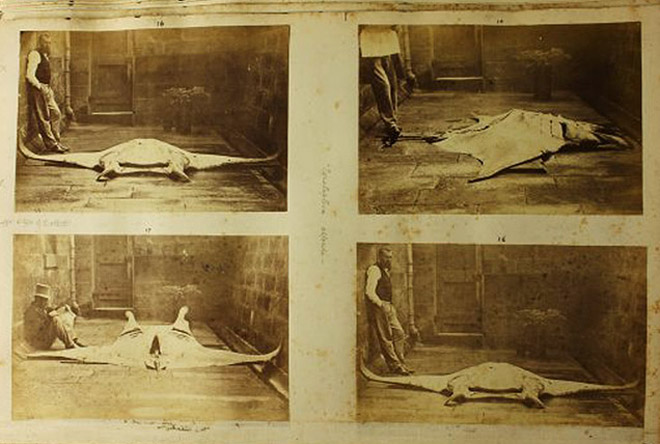

Double act: Gerard Krefft and the Alfred Manta, Manta Alfredi (1868), by Henry Barnes, holotype. © Australian Museum

By including scientific photos, The Photograph and Australia alludes to photography’s status as the most mechanical of the arts, and to the way it marries the scientific and the aesthetic, often to the point where they are barely distinguishable. In some of these “scientific” images, we can quite clearly see how the photographer has consciously invited an overlapping perspective. In the extraordinary set of images by Henry Barnes entitled Gerard Krefft and the Alfred Manta, Manta Alfredi (1868), Krefft and the manta ray perform a double act, each adopting quite different poses in each of the four frames. As Kathleen Davidson points out in her essay on colonial scientific photography in the exhibition book, the fact that we see the manta ray from front, back and both sides is perfectly in accordance with the conventions of scientific documentation.

Rather less scientifically, Krefft appears in a variety of poses that seem to have been thought up on the spur of the moment, thereby emphasising the quirkiness of the object of interest – the manta ray – and the strange incongruity of this vast sea creature appearing as it does, preserved and carefully placed on the stone floor of a room that barely contains its full span. The modernity of the images derives not only from Krefft’s showy informality but also from the fact that he, as a museum curator, is present and on view, a reminder of the role the curator plays in determining what we see and how we see it.

Indeed, the curatorial function is inherent in the practice of photography itself, in the sense that all photography involves selection, from choice of subject to choice of final print. “I find 99.9 per cent of the frames on the contact sheet are mistakes one makes while photographing,” says the New York photographer Leonard Freed in the absorbing, recently reissued book Magnum Contact Sheets, a reminder that every photograph we see has typically been chosen from an array of other contenders that we do not see but that survive somewhere, in physical or electronic form.

In one of two photographs by Robyn Stacey in The Photograph and Australia, Chatelaine (2010), the curatorial and photographic impulses combine to convey the essence of an historical collection of objects and artefacts and the lives it represents. The nineteenth-century world of Vaucluse House in Sydney, former home of the Wentworth family, is conveyed through an arrangement of objects belonging to or associated with the house. The title of the photograph points the viewer to the chatelaine in the bottom left-hand quadrant, the “feminine version of a Swiss Army knife” that belonged to Sarah Wentworth and was designed to be worn around the waist, its scissors and other handy household devices being easily available if required to modify or trim or otherwise enhance the overall domestic display. The flowers, also selected for their association with the house and with the gardening fashions of the time, are reminders both of life – somebody cut the flowers, somebody arranged them – and temporality. The way in which these “old-fashioned” flowers have been arranged, in a more casual-seeming contemporary way, seems to link the present day to the formality of an earlier time.

Arrangement and understanding: Chatelaine (2010), by Robyn Stacey, from the series Tall Tales and True, type C photograph.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds from the Photography Collection Benefactors Program 2011. © Robyn Stacey.

Robyn Stacey has built a significant reputation on her practice of photographing collections, not as a comprehensive, “scientific” process of documentation but as a process of arrangement and distillation. Her beautiful, dramatically lit images, with their allusions to the fashion for staged photography, position the essence of a much larger collection within a single frame. Stacey applies to Australian history a methodology that early Australian photographers applied to the contemporary sights and subjects that confronted them, collecting and placing and arranging as a means to understanding. Examples of “arranged” photographs abound in the exhibition: in Fred Kruger’s artfully organised collection of Victorian Aboriginals’ War Implements, Coranderrk (c. 1877), for instance, or Charles Bayliss’s Eight Lawrence Hargrave Flying Machine Models (1885), in which Hargrave’s models are grouped together for their family photograph, like bugs in a cabinet of curiosities.

By contrast, in the several examples of composite (or mosaic) photography in the exhibition, we can see how this process of arrangement followed by photograph – line up your subjects and then take the picture – is reversed. First comes the image (or rather images), then the arrangement. In 1867, Patrick Dawson photographed, in his Warrnambool studio, the members of the first Aboriginal cricket team to tour England. He then arranged the individual oval images within a larger oval, which is further contained within a conventional rectangular border: frames within frames. Some of the men are in cricket whites – one man bowls, another bats. Others are shown in a variety of sporting gear, holding a boomerang perhaps, or a spear. The poses seem highly staged to the modern eye, the visual references – to Indigenous culture, to Europeanisation, to cricket – are all over the place, but for all that Dawson’s Aboriginal Cricket Team of 1868 is among the most successful of the composite images of the period.

New South Wales Contingent. Soudan Campaign. 1885 (c. 1890), by Barcroft Capel Boake. Australian War Memorial

The variations of costume and pose emphasise the individuality of the men, while the formality of the arrangement points to their interconnectedness. We can see they are a team. A more ambitious, and more overwhelming, example of this composite or mosaic technique can be seen in Barcroft Capel Boake’s elaborately over-the-top concoction made up of individual photographs of members of the NSW military contingent to the Sudan campaign of 1885 (above) or, even more startlingly, in Henry Jones’s arrangement of oval portraits of Old Lady Colonists, completed in 1871. Jones has placed “hundreds of tiny paper photographs” of these pioneering women in rows of varying length, one above the other. The process took years. The final, composite image is both celebratory and anonymising. The effect is of a very early example of concrete poetry, in which form competes with content for the viewer’s attention, with neither quite gaining the upper hand.

These early composite photographs highlight, in a rather theatrical way, the natural human impulse to group photographs, and to use photography as a way of imposing order. Settlers in a new and unfamiliar landscape would have been particularly susceptible to this impulse to document and define, to capture individual moments and create pattern out of them. Indeed, the exhibition as a whole places a welcome emphasis on the interconnectedness of photographs, raising the question of whether a single image can ever really be seen in isolation. In an essay in the exhibition book, Martyn Jolly considers the extraordinary popularity of the photograph album in nineteenth-century Australia. Collections placed in albums were a means by which the owners also placed themselves, summarising their lives and their interests in order to be seen as they wanted to be seen. The global phenomenon of the photograph album became a means of locating its owner in the new world.

The images so carefully displayed in albums were typically in the form of cartes de visite. These small photographs, stuck onto stiff card, were originally intended as calling cards but rapidly become collectible for their own sake. Images of friends and family members, or of people one admired, envied or just liked the look of, interspersed perhaps with landscapes or architectural photographs, were combined between hard covers to form a curated version of the album’s owner. But just as photostreams and Flickr albums and Instagram accounts can’t hope to organise and contain all the images available online, so only a proportion of the vast numbers of cartes de visite would end up trapped in albums – the rest floated free, subject to no particular organising principle.

Here, on the gallery walls, surviving examples of these small images from the second half of the nineteenth century are displayed in grid formation, with the viewer left to make connections and comparisons as the eye is drawn to one image or another from among the many to choose from. Seen in this way, it is clear how the size of the images serves to contain the subject – individual portraits, family groups, landscapes and buildings, all are effectively miniaturised. It is no surprise that in this form they were eminently collectible.

At the same time as photography was capturing the Australian landscape and the resulting images were being stuck onto small pieces of card, it was also showing how vast and uncontainable that landscape could be, and how easily it could be imagined as extending well outside the frame. This effect can be seen in scientist and photographer Walter Baldwin Spencer’s wonderfully evocative View of Roper River, Northern Territory, Australia (1911), in which the river dominates the lower two-thirds of the frame as it can be seen extending to vanishing point in the background, or in the American Melvin Vaniman’s Panorama of Fitzroy Vale Station, Near Rockhampton (1904), in which the positioning of the trees suggests a repeat pattern that will stretch on forever on either side, far beyond the metre-long print. In the Spencer image, the landscape is in its natural state. In the Vaniman, it has been improved. Trees have been felled and houses built. Yet the serenity of the image suggests the full meaning of the word “improvement” – it is nature made even more aesthetically pleasing by human intervention.

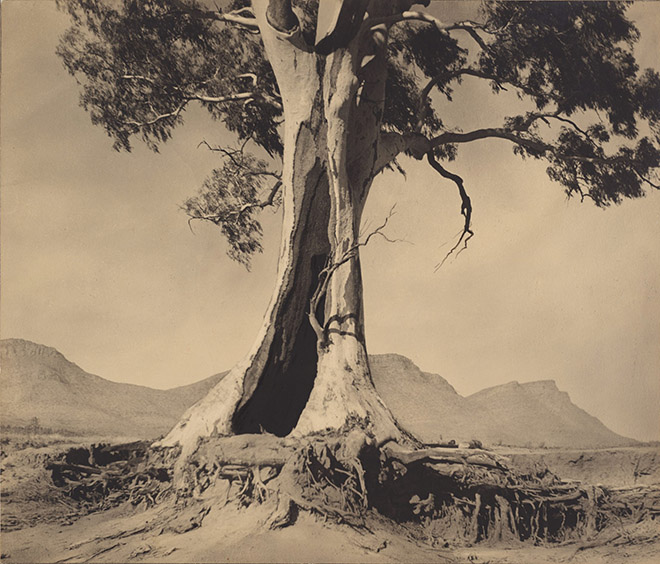

Monumentality: Spirit of Endurance (1937), by Harold Cazneaux, gelatin silver photograph. Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of the Cazneaux family 1975

Other, chronologically later photographs show a very different relationship to the landscape. Harold Cazneaux’s Soil Erosion Near Robe (1935), with its baldly factual title, demonstrates its theme by means of an aesthetically pleasing composition. A group of shells, appearing out of their natural element “forty to sixty feet above sea level,” is shown in sharp focus in the foreground, as if the shells have been brought there by a combination of natural forces and artistic intent. In one of Cazneaux’s most famous photographs, also included in the exhibition, we are clearly directed by the title – Spirit of Endurance – to see the huge gum, its roots exposed, its trunk hollowed out and its monumentality emphasised by the angle of the shot and the severe cropping of the image at the top, as an analogue of the resilience required for human habitation of this land, even as it may also lead us to reflect on the damage that human habitation can inflict. To the contemporary viewer, Cazneaux’s dramatically anthropomorphic image of the Australian landscape may seem to be overdoing it rather, particularly in the context of more recent work by artists such as Anne Ferran and Rosemary Laing, who aim to elicit a more reflective and cumulative response in the viewer.

Anne Ferran’s five large-format, monochrome photographs, taken from her 2008 series Lost to Worlds, show repeated views of a minimally differentiated patch of ground that occupies almost the entire frame. It is not certain that we would understand even this much without the benefit of the information in the exhibition book. We could, perhaps, be looking at the moon. What we are looking at, in fact, is the ground on which stood the Female Factory in Ross, Tasmania, which evokes the presence of the “women and children who lived and died there” between 1847 and 1854. Just as we are led by Cazneaux’s title, Spirit of Endurance, to see his photograph in a particular way, here we are led to infer the human presence that once occupied this site, and the reality of the suffering that was endured by those who were consigned there; the shadowy shapes on the ground become traces of that suffering. Ferran’s work reminds us of how difficult it can be to interpret an image based on the image alone.

Devoting more than passing attention to any single photograph will prompt us to wonder what happened before and especially after the photographic moment. Sometimes, with images of famous people or iconic landscapes, we roughly know the answers, but for the most part we do not. In that sense, photographs naturally encourage speculation. “When we look,” writes Judy Annear, “we inevitably compare – what a place or person was like then, with what they are now.” We imagine other photographs, in the form of a sequence that focuses on the same subject and stretches over time. Or, as Annear puts it, “we consider how these things might be next time they are photographed.”

Nowadays, putting that consideration into practice couldn’t be easier. The Everyday app (“life goes fast – capture it”) will remind you that it’s time for that daily selfie. Progression videos or flipbooks abound on YouTube and other platforms, compiling daily self-portraits that show the subject ageing over time – a year, two years, ten years. (The record so far seems to be twenty-seven.) Given that these compilations do answer our question about what happened next, to say nothing of next and next and next, it is curious how difficult it can be to resist the temptation to jump ahead and get it over with. The sequences lasting two minutes seem to run for a very long time and the five-minute ones feel like eternity. They tell us we are getting older, which does not in the end seem quite enough for a photograph, or a series of photographs, to say.

Sue Ford’s series Self-Portrait with Camera, comprising forty-seven images of herself made at intervals between 1960 and 2006, must be seen now through the prism of this current fashion for regular visual updates. Given the speed with which the practice of re-photographing has become a cultural cliché, it might be expected that Ford’s sequence of self-portraits would suffer as a result, but in fact her work gains by the comparison. It would not convert easily into a flipbook; instead, it is a meditation on the photographer’s relationship with the camera, with family and friends and subjects, and with her own photographs. In many of the images Ford’s face is obscured, by vegetation, by her hand or her hair, by her camera, and once by a joker from a pack of cards that she holds up in front of her face. The poses suggest a combination of self-deprecation and determination, of the blurred lines between photographer and photographed. The process of ageing itself seems secondary to the project – it is something both more complicated and more satisfying for the viewer, an autobiography in pictures.

Certain photographic genres are under-represented in this exhibition. Photojournalism, for instance. Not to mention glamour shots, mug shots (there are two, both of a certain Edward Kelly, one with beard and one without – “scar top and crown of head, eyebrows meeting”), aerial shots, or snaps of families and of holidays and of families on holiday, untold examples of which are held in archives across the country. Some might find that these relative absences, together with the emphasis on the nineteenth century, and on nineteenth-century portraiture in particular, unbalance the story of how “photography invented Australia.” But another way of looking at it is that a keen curatorial eye and expert knowledge of Australian photography have rebalanced the picture.

In our current fixation with the ubiquity of photography (updates on the total number of images in existence are now given in the trillions), we can forget that photography has tended towards over-production from quite early on in its history. The exhibition’s coverage of the carte de visite phenomenon provides a clear example. All of which makes choosing difficult. An exhibition that looks at the relationship between Australia and the photograph cannot possibly be comprehensive, or anywhere near comprehensive, but it can, as The Photograph and Australia successfully does, make new and illuminating connections across the full range of Australian photographic history. •