The title of Kwame Anthony Appiah’s latest book, The Honor Code, sent a shudder through my gut, probably because I’ve read too many reports lately in which the word “honour” was immediately followed by the word “killing.”

It stirred memories of a conversation I once had with Shahtaj Qazilbash at the office of the law firm in Lahore where she worked as a paralegal. Qazilbash had more reason than most to recoil from the debased use of the word “honour.” A year before our discussion, a client called Samia Sarwar had come to the office for a meeting with her mother. Samia had been estranged from her family ever since she’d sought help from prominent lawyer Hina Jilani to divorce her abusive husband. Her parents had initially refused to countenance the shame of a divorce in the family, but the meeting between mother and daughter was meant to be a first step towards reconciliation.

The reunion was short-lived. Samia’s mother was accompanied by her uncle and a driver. Once inside, the driver shot Samia dead and threatened to kill Hina Jilani before being killed by a security officer. Samia’s uncle took Qazilbash hostage at gunpoint and used her as a shield as he and Samia’s mother retreated to the hotel where her father was waiting to be told that his wayward daughter would bring no further shame on the family.

Samia’s death received more publicity than most such killings, partly because it happened so publicly and partly because her family belonged to the urban elite. Wealthy and well connected, they were never held to account for her death, and their crime was defended by the political establishment of their home state.

As Appiah relates, thousands of women are murdered every year in the epidemic of honour-related violence that he describes as a “war on women.” Samia Sarwar’s death plays a central role in his discussion as he asks why her killers went unpunished and, most crucially, whether honour killings can be consigned to history not by attributing less value to honour but by reframing the definition of honourable conduct.

Appiah’s purpose in The Honor Code is to suggest that apparently deeply entrenched practices such as honour killing need not be regarded as regrettable but insurmountable social ills. He precedes his discussion of honour killing with analyses of duelling, foot-binding and slavery — long-established social practices that relatively quickly made the transition from ubiquitous (at least in the social circles that upheld them) to obsolete. Just as honour may have been the underlying rationale behind these customs, honour also became the reason for abandoning them, as once-honourable practices came to be seen as shameful, primitive or, in the case of duelling, ridiculous to the point of embarrassment.

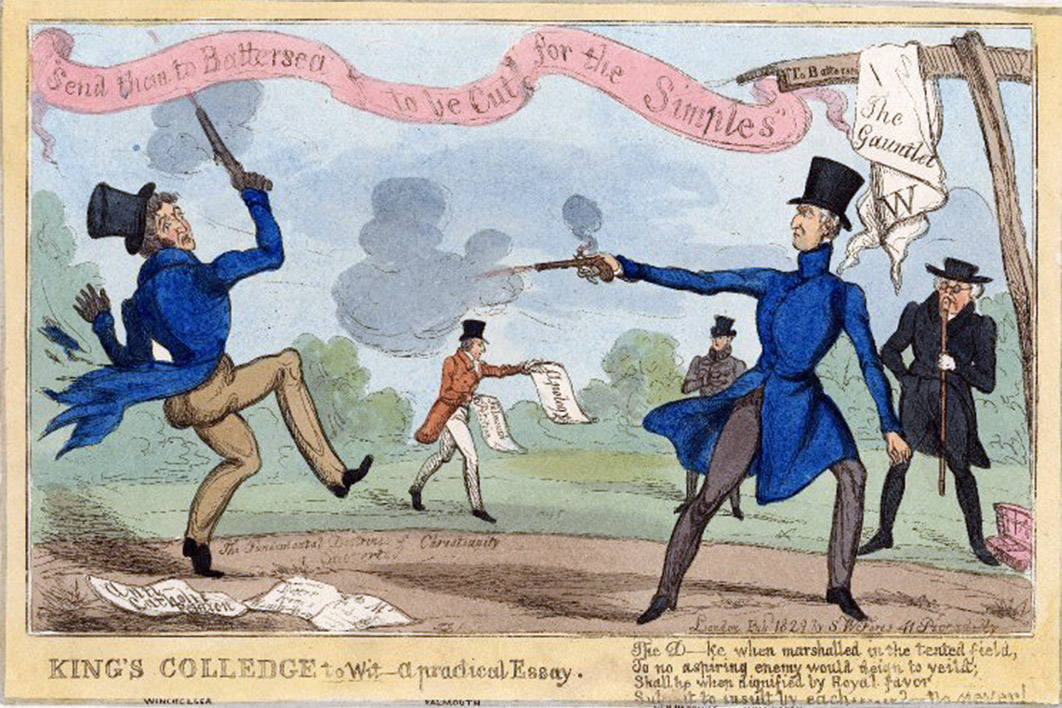

Appiah’s opening anecdote certainly does sound comically ridiculous to contemporary sensibilities. In 1829, the Duke of Wellington, prime minister and hero of Waterloo, was accused of deceptive conduct during the debate over Catholic emancipation. The Catholic Relief Act, which would allow Catholics to sit in parliament, was strenuously opposed by the Earl of Winchilsea, who claimed that Wellington was using his support for the Anglican King’s College as a distraction from his “introduction of Popery into every department of the State.” This slur on Wellington’s honour couldn’t be allowed to stand, and the prime minister demanded satisfaction. After all, Wellington and Winchilsea were both gentlemen, and duelling was the recognised means of resolving questions of honour.

After a token exchange of gunfire in a field near Battersea Bridge, Winchilsea’s “second” handed over a pre-prepared apology and the two gentlemen retreated, with Wellington’s honour redeemed to his own and his peers’ satisfaction. Neither gentleman faced any legal consequences, and Wellington’s political career was secure. Yet duelling was technically illegal and widely regarded as immoral. Appiah asks how a practice that was openly tolerated would become practically obsolete a few decades later.

In fact, the factors that would lead to the duel’s demise were already visible in the confrontation between Wellington and Winchilsea. The honour code was still powerful enough to support Wellington’s claim that he had no other choice but to defend his honour against Winchilsea’s outrageous slur. Yet, Appiah suggests, while Wellington was able to portray himself as a gentleman forced into a regrettable situation in which he had no option but to demand satisfaction, he was also deploying the defence of his honour as a political tactic — an altogether less elevated motive.

The somewhat ritualistic nature of the Wellington—Winchilsea encounter is another indication that the duel had become a less serious affair. Honour dictated that Wellington issue the challenge and Winchilsea accept it, but only two shots were fired. Wellington’s shot went wide and Winchilsea fired into the air — not really in the true spirit of duelling, as observers of the time noted.

Suggestions from some quarters that Winchilsea ought to have been beneath Wellington’s notice undermined the assumption that gentlemen met on the duelling field as equals. At the same time, the aristocrats for whom duelling was an accepted social practice were losing their elevated social position as the middle class assumed an ever more important role. Gentlemen’s foibles became more visible and open to ridicule, with the Wellington—Winchilsea encounter the subject of mockery and cartoons. Over the following years, duelling ceased to be the exclusive preserve of “gentlemen,” as disputes among the lower orders came to be framed in its language. A social norm that allowed the aristocracy to break the law and transgress accepted moral standards was no longer sustainable. And as the duel lost its social cachet, the gentlemen in question no longer wished to engage in it. Honour was no less important, but duelling had ceased to be honourable.

Appiah draws a connection between duelling in Europe and foot-binding in China, describing both of them as elite honour practices that withered under external scrutiny. Foot-binding effectively crippled women and girls, which meant that the practice was confined to those who didn’t need female labour. But bound feet were also an essential attribute for the wife of an upper-class man, thus ensuring that the practice was adopted by families that aspired to raise their social rank. As with duelling, foot-binding lost some of its sheen as it was taken up by the lower orders. Its prevalence lowered its value and provided a mechanism for its abolition.

Foot-binding was criticised within China even before it was denounced by American and European missionaries. These criticisms made few inroads while China remained self confident and self contained; but as China redefined itself as a member of the global community — and a member that was facing decline — foot-binding came to be seen as a source of national shame. No longer associated with prestige, it was increasingly viewed through the lens of international scrutiny, and the tiny feet that had been extolled as beautiful instead appeared barbarous and embarrassing.

Appiah cites the slave trade as another practice that was widely seen as morally abhorrent but was resilient in the face of criticism until it also came to be seen as shameful. He acknowledges but dismisses the argument that slavery was abolished because it no longer made economic sense. In his opinion, honour was more than just a cover for self-interested motives. It was a means by which abolitionists could not only frame their cause in terms of virtue but also portray inaction as a source of shame. The British abolition movement harnessed support from both the middle and the working classes, tying the struggle for the emancipation of slaves in America to their own claims for an appropriate level of respect. “[Slavery’s] unequivocal meaning was that manual labor was to be equated with suffering and dishonour,” writes Appiah. “That was why it could be used to speak of the suffering of those who were not literally enslaved.” Slavery, then, dishonoured even those who were only indirectly implicated.

Remembering the shelves of files in Shahtaj Qazilbash’s office, each folder containing a story of tragedy and injustice, I hope that Appiah’s optimistic belief in the power of honour to achieve liberation as well as oppression proves justified in the case of honour killings. “There is no honour in honour killings,” campaigners repeat, but even those who claim to oppose the practice often blame the activists who publicise the violence, rather than the perpetrators who commit it, for the dishonour it brings to Pakistan’s name.

Appiah closes his book with the story of Mukhtaran Bibi, a Pakistani village woman he calls a “model of honour.” Mukhtaran was sentenced to be gang-raped by the upper-caste men of her village in retribution for her brother’s alleged transgression, but rather than buckle beneath the shame she reported her attackers to the police. Her case was eventually taken up by the lawyers who had represented Samia Sarwar.

Once her story gained the attention of the international media, Mukhtaran was held responsible for causing Pakistan international embarrassment. Explaining why she had been denied an exit visa to receive an award in North America, then president Musharraf told the Washington Post, “This has become a money-making concern. A lot of people say if you want to go abroad and get a visa for Canada or citizenship and be a millionaire, get yourself raped.” But, as Appiah relates, Mukhtaran continues to speak out and used the compensation she eventually received to establish a girl’s school in her village.

THE Honour Code is a narrative of human progress, and its account of “moral revolutions” means that it is an optimistic book, despite the sometimes grim stories it has to tell. I was cheered, but also left wondering whether honour simply demands that oppression should be kept out of sight or presented in a more palatable form. Little girls in China no longer suffer the torture of foot-binding, but more and more women around the world undergo sometimes dangerous cosmetic surgery in pursuit of self-worth. We no longer tolerate institutionalised slavery, but we continue to purchase mass-produced clothing even while knowing that it is probably manufactured in slave-like conditions. As Appiah notes, morality in itself is an insufficient force to generate social change.

In current political discourse the word “honour” generates cynicism. It’s a word treated with appropriate seriousness on Anzac Day and after national tragedies such as bushfires or floods, particularly in relation to those whose actions have gone beyond the call of duty. As Appiah says, honour provides motivation and reward for deeds that could not be either demanded or purchased. The word’s indiscriminate use devalues it, however, which perhaps explains why it sounds so cheap when used for political purposes.

Among the more recent moral revolutions, the apology to the stolen generations seems like an exercise in re-attributing honour. Australians gained a heightened awareness of the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families following the 1997 publication of the Bringing Them Home report. The damage inflicted on the stolen generations and their families and John Howard’s steadfast refusal to acknowledge them in the form of an apology had both become a source of national shame. Kevin Rudd opened his “Sorry Day” speech with the words, “Today we honour the Indigenous peoples of this land,” but the apology that followed was first and foremost an attempt to redeem the honour of non-Indigenous Australians. In those terms, it was highly successful, but the continued vulnerability and disadvantage experienced by too many Indigenous people indicate that we redeemed our honour at a bargain-basement price.

As I read The Honor Code I began to speculate about which contemporary taken-for-granted social practices might crumble in the face of moral revolution. We have no moral consensus over how (or whether) the sex industry should be regulated. The commodification of human body tissue seems to be gaining rather than losing acceptance, with governments under pressure to allow payment to surrogate mothers and organ and bone-marrow donors. Support for euthanasia seems to be gaining momentum. Environmentalism seems ripe for a transformative moral revolution — or perhaps not. In a century or two, people may need to strain to imagine what life was like before the moral revolutions that transformed these issues — or they may find it hard to believe that a change to the status quo was ever seriously suggested.

“There is no honour in honour killing.” There is honour, however, in Shahtaj Qazilbash’s courage in returning to work in the office where she had witnessed a murder and been kidnapped at gunpoint. Sadly, as Pakistan descends further into chaos, violence against women is increasing, and much of it is committed under the banner of honour. And women are not the only casualties. The most high-profile recent victim is Salmaan Taseer, the blunt-spoken governor of Punjab who had come to the defence of a woman accused of blasphemy — the sin of dishonouring God. Taseer’s uncompromising stance against the blasphemy laws cost him his life. He was gunned down by one of his own bodyguards — and his assassin was “honoured” by a crowd of lawyers who garlanded him with flowers when he was taken to court.

In retrospect, Taseer’s determined stance against the blasphemy laws seems quixotic — but then, Don Quixote was nothing if not a man of honour. •