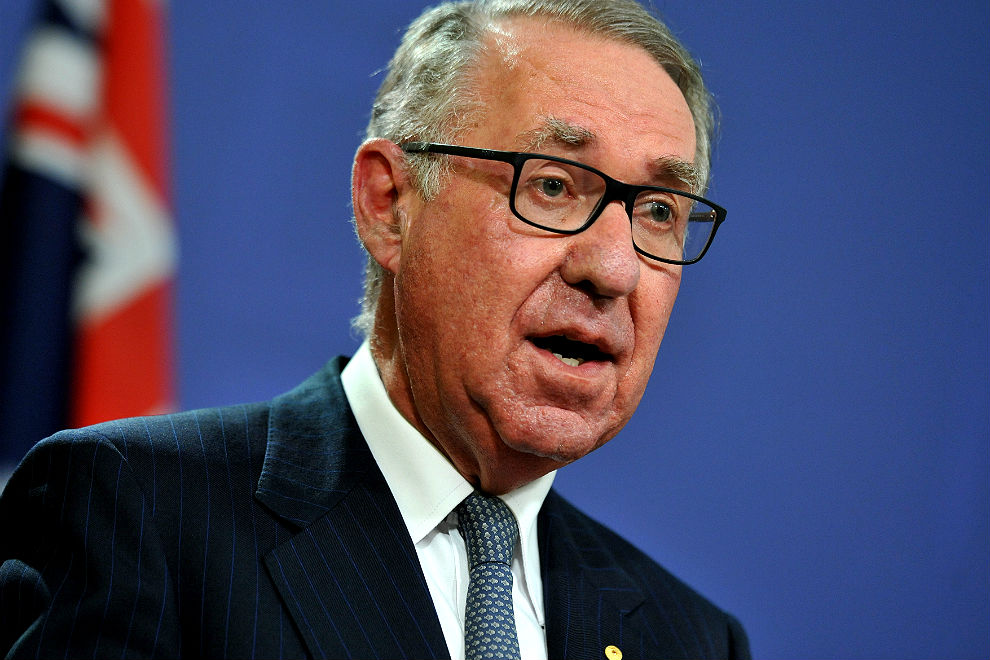

It was not, as education minister Simon Birmingham declared, a “momentous” day for schools, but it was a big one: against almost all expectations (including mine), a Coalition government has announced that it will do a Gonski. Sort of. Probably.

The government says it will introduce needs-based, sector-blind funding for all schools, and spend more money over the coming decade to do it – all straight out of Gonski version 1. What’s more, it will get David Gonski, together with Gonski 1 panel member, the redoubtable Ken Boston, to fix one of its weak spots, making sure that more and better-distributed money does the needful. Gonski 1 was merely a “review of school funding.” Gonski 2 is a Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australia.

In its attempt at that very big ask, the review will face substantial obstacles, in the structure and politics of schooling, in the habitual practices of schools, and in unmeetable expectations.

The structure of schooling

Gonski 1 was asked to make workable Australia’s unique and dysfunctional Rubik’s Cube, a school “system” comprising two levels of government, both of them heavily involved in each of three sectors, a two-by-three set-up replicated in each of eight states and territories.

The Gonski fix was ingenious but, thanks to its terms of reference, far from complete. It recommended that state/territory and federal governments agree on a funding total and their respective contributions; that every school gets a basic level of funding plus loadings according to the size of its educational task, as indicated by its location and demographics; that the loadings go direct to the schools concerned; and that a new “national schools resourcing body” should oversee the new allocation system and do the research needed to refine it.

All that was a big improvement on what everyone agrees was a wildly inequitable and haphazard set-up, but it did not dismantle the Rubik’s Cube.

The federal government would continue to be deeply involved in the schools business, against very good arguments (including several pushed by Coalition governments) for getting the Commonwealth out of schooling altogether.

It left the fee/free distinction intact, and hence left those families struggling to pay to go on struggling while other families, well able to pay, went on enjoying the free schooling provided by government schools, and often in de jure or de facto selective schools, at that. It left the fee-charging schools able to charge whatever they liked, and guaranteed that none would be worse off in any future funding regime.

Moreover, Gonski 1 was prohibited from saying a word about the bizarre arrangement that allows some schools to select and exclude according to religion and/or capacity to pay and/or academic capacity, while others are forbidden to select or exclude anyone at all – a rigging of the regulatory game that, in tandem with funding arrangements and the real estate market, has been driving high and rising levels of social segregation and educational inequality for forty years.

That was Gonski 1. There is nothing in the government’s announcements to suggest that Gonski 2 will be asked to review any of these fundamental structural problems. Nor is there any reference to reinstating Gonski’s proposed national schools resourcing body, which would have moderated the structural problem.

The practice of schooling

The government’s rhetoric in announcing Gonski 2 is as myopically fixed on “outcomes” (aka PISA results) as its predecessor’s. Schools don’t and shouldn’t just produce “outcomes” in this or any other sense. At least as important are what students learn about themselves and others in and through the “informal” or “hidden” curriculum, and the quality and character of the experience of being at school. Schools should be encouraged to pay as much attention to their “performance” in these areas as to academic outcomes. In that, Gonski 2 has been given a bad start.

It also inherits other problems from Gonski 1. The first Gonski’s argument was that the harder the educational job, the more resources the school needs to do it. Gonski did not see this as just a fair go or a helping hand, but as the price of delivering an educational service. That is why it wanted the extra money to go direct to the schools concerned – so that they, in turn, could buy the services they needed to deliver in their specific circumstances. As well, Gonski wanted to maximise the impact of new money by concentrating it in a relatively small proportion of schools.

This commendable approach came with several problems: it depended on the schools’ bureaucratic masters to pass the money on, which, in scattered attempts at “implementation,” some did and most didn’t; it depended on schools knowing how best to use the new money; and, in the nature of being “extra,” it left the expenditure of the great bulk of the school’s resources going on doing what they have always done, which does not include deploying effort according to need.

Of these several limitations, the last is the most important. Doing a Gonski across schools is only half of the job; the other is to do a Gonski within each school.

Politics

The Rubik’s Cube might have been deliberately designed to generate conflict, and to give any aggrieved party, sector or government an effective power of veto.

The Catholic systems, easily the best-organised and most relentless of the veto-possessors, have already made unhappy noises about Gonski 2. Their allies in the independent sector will probably be more circumspect in public, but not behind the scenes.

Then there are the states and territories. The education minister says that he “looks forward to working constructively with states and territories to see implementation of these reforms” and that “delivery of reforms will be a condition of funding for states.” Good luck with that. His first offer is substantially below that once proposed by Labor, and the risk is that Gonski 2 will, like its predecessor, degenerate into a stand-off over funding amounts and shares.

And, finally, the politics. Last time around the problem was between the parties. That will be joined this time by the clash of ideologies within the Coalition. Tony Abbott and others have professed a sense of special affiliation with and obligation to the non-government sectors. Can Turnbull carry the day within his own party room? Indeed, come December, when Gonski presents his second report, will Turnbull still be prime minister?

Expectations

In the eighteen months between the release of the Gonski report in February 2012 and the federal election in September 2013, the campaign in support turned into a near-crusade. Gonski became in many minds a miracle cure, the answer to all of the many problems in schools and schooling.

The prime minister and his education minister have already reignited those flames with talk of ending “150 years of inequity” and delivering “consistency in Australian school funding for the first time ever.” Turnbull and Birmingham risk joining a long list, headed by Gough Whitlam, of those claiming to have put the “state aid” problem to rest. As for “achieving educational excellence in Australia,” the depth and complexity of schooling’s problems are such that Gonski 1 was only one step of several required. Gonski 2 is guaranteed to be a failure, and to be seen as one, if it is expected to “achieve educational excellence in Australia.”

Managing the impossible

Gonski 2 cannot solve all those problems, but it can manage them.

• It should manage expectations by saying very clearly that neither it nor any other single-focus reform can do the needful. It might underline the point by citing a list of necessary reforms prepared by the head of the Australian Council for Educational Research. Gonski 2 should also suggest that governments make good use of the next few years to work out what to do at the expiry of any agreement it might recommend, including what to do about the many remaining components of the Rubik’s Cube – the fee/free distinction, federal government involvement in schooling, and the current regulatory mess particularly.

• The second Gonski review should say that academic outcomes and their more equal distibution are fundamental, but so are other things. It should point out that the character and quality of life at school and “social” learning are at least as important and as easy to measure and report on as “outcomes,” and should be treated as such.

• Most schools have little or no experience in deciding how to spend money to greatest educational effect – that is, in finding the most cost-effective interventions. Nor do most researchers, captivated as they are by “effects,” with no consideration of costs. A very good start has been made elsewhere in finding out how to get most bang for the educational buck, and how to help schools do it. Gonski 2 should recommended a substantial program of R&D – not “research” – to adapt that approach to Australian circumstances.

• Gonski 2 should also suggest that new dollars be used to free up old ones, to mobilise the resources that already come through the school gate in frozen form. It should recommend that the government encourage the industrial parties to sit down and work out how to give schools more scope for aligning resources with need. It might even make the specific suggestion that the best starting point would be a move from fixed class size maximums to average class sizes.

• Gonski 1 recommended a new “national schools resourcing body.” No new funding scheme can work without it or its equivalent, and Gonski 2 should say so.

A final recommendation, not for Gonski 2 but for its political masters.

Gonski 2 can only succeed on a broad base of support. That does not exist. It must be built. In their announcement of Gonski 2, the prime minister and his minister headed in the opposite direction, blaming Labor for “trading away the principles of ‘Gonski’ for political expediency,” and claiming that it is “acting to right Labor’s wrongs.”

It is true that Labor bungled the Gonski process and delivered a new arrangement almost as incompetent as the old. But two other things are also true. Gonski was Labor’s idea in the first place. As can be seen from the several reviews generated in the early days of the Coalition government, had it been left to the Coalition it would never have come up with anything like Gonski. If Labor is going to get blame for the bungle, it should also get the credit for the only fully fledged, carefully thought-out, politically smart, well-evidenced and well-argued schooling reform strategy in many decades.

And if the Coalition is going to hand out blame, it should also cop it. Senator Birmingham’s predecessor played the Gonski spoiler from the moment of its release, opposing it root and branch, and fomenting opposition and subversion by his Coalition colleagues in the states and territories. Worse, at the eleventh electoral hour in 2013, when Gonski looked like a winner, the predecessors of the present prime minister and education minister declared a “unity ticket” on Gonski, then tore it up again the moment they were safely in office.

If teacher organisations and others fail to trust Gonski 2, the government has only itself to blame. It has the chance to redeem itself, but it won’t if it prefers cheap political shots to giving Gonski 2 a platform of consensus from which to speak. •

Any thoughts? Comment below...