Brooklyn

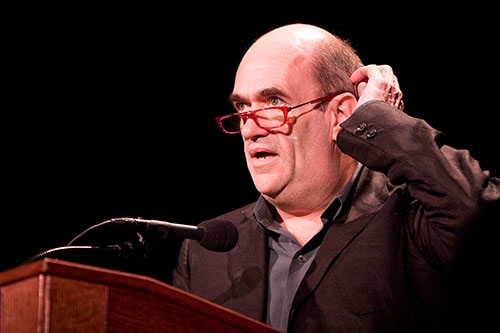

By Colm Tóibín | Picador | $32.99

COLM TOIBIN is one of the finest realists at work in fiction today. The fact that his art is so plain and so elegant makes it proof against excesses born of fashion and pretence, even if the risk, as always with someone who aims for an effect of truth by traditional means, is the deadly one of dullness.

In practice his work varies. The Heather Blazing, the story of an old judge remembering the injustices of the Troubles a lifetime earlier, is his Wild Strawberries, an untouchable, God-given masterpiece. The Blackwater Lightship is a fine and moving story of death in a family and the comings together that are effected in a time of travail. The Story of the Night, on the other hand, is the book in which the author seems to take his sexual predilection for a ride, almost a Mills and Booner. The Master, which aims to be the opposite in its elaborate homage to a re-claiming of Henry James, pleased a multitude of a literary caviar lovers, but looked like grandiose and self-conscious vulgarity to me.

The short stories vary as to vividness but exemplify the ‘scrupulous meanness’ Colm Tóibín takes from early Joyce, in defiance of all subsequent blarney or experimentation, all highbrowism or opportunism. The last one I read (in the opera-inspired anthology Midsummer Nights) was about priestly shenanigans in a school and was about as grave and authentic as fiction, in small compass, gets.

Brooklyn is cut from the same cloth as the stories and might indeed be an expansion of what was originally intended as one. A young woman lives, without much in the way of expectation, with her mother and sister in an Irish town. The sister, sprightly and extroverted, does something to do with golf. The protagonist, intelligent and quiet, gets a job in a grocery store working for a repressive Irish witch until some priest has the happy idea that she should emigrate to Brooklyn.

Here she takes up residence in the boarding house of another Irish virago (in fact a distant relative of the other) and earns a crust working in a department store while studying bookkeeping at night. Quiet pointers here and there indicate effortlessly that it's the early Fifties – people are still enthused about nylon and the store initiates a policy of selling stockings (at first bright red ones) to black women. She goes with a boy to see Singin’ in the Rain, which has just been released.

That boy is a plumber from an Italian family who falls passionately in love with her. The latter part of the book sees the heroine back in her native Ireland wondering whether she wants the passionate American boy or a strapping, though introspective, son of publicans who would hitherto have seemed too good for her.

Brooklyn is one of those novels that is quiet to the point of mousiness. It exactly recaptures (and presents as if new-minted) the refined, slightly stilted vividness of genteel Irish speech with a marked emphasis on feminine evasion and savagery. It is compellingly real if looked at fairly, even though the technique can seem like a great wash of watercolour in which the mystery of the everyday is presented as so many subtlised shades of grey.

It’s a closed down Catholic catastrophe of a world Colm Tóibín reveals to us, as tight as a confessional box, though part of the energy of the book is to indicate, with great understatement, the fires that burn, however palely, beneath these buttoned up feminine fronts.

No one is better at capturing in fictional form what the historian and one-time Jesuit Greg Dening meant when he said that there was an age of licence at the heart of every closed system that alone makes it tolerable. It’s as if Tóibín has gone from salivating and cerebrating round the unacted-on homosexuality of Henry James to the recognition that every form of apparent repression – in particular the Irish-Catholic cult of maidenhood – is capable of disclosing great gulfs of desire and passion and complexity.

It's what Germaine Greer meant by the stimulating degree of restraint in Jane Austen. This young Irishwoman wants to be true to the faith that gives her morals (and in fact she perceives them herself quite consciously as a seamless web) but at the same time she is swept up in what becomes a very traditionally represented questioning of the different faces of love and of male desirability.

Does this make Brooklyn a case of Mills and Boon at one remove, a form of Boys’ Own romance in drag? Not at all, however feasible the insinuation might seem.

Colm Tóibín writes about his young Irishwoman with an impassioned empathy that makes her absolutely believable through the various twists and turns of a story that is minimalist in outline and largely monochromatic in colouring. Brooklyn convinces by virtue of its inch by inch insights into the workings of a minute world. Yes, it does flood for moment or two with the apparition of male attractiveness but that quality comes across with such authenticity because the novel is working so much by principle of tact. It's not a novel of dappled surfaces or indeed of anything in the way of high drama, so that its touches of catastrophe and sex have a kind of crescendoing force compared to everything else.

If Brooklyn has a disadvantage it’s that the control of tone, the meticulous avoidance of melodrama and the highlighting of significant shifts in the action, makes the book a bit like a short story that has been magnified extraordinarily under the microscope. Characters flit across dance floors and streetscapes almost anonymously. Worlds of characterisation are done in the flat with only the surge and lilt of the dialogue to indicate human intensity. It's a world where people swim in and out of the main character’s awareness and sense of hierarchy.

At times this means that the narrative seems to strain to find significance in the relentlessness with which it orchestrates the everyday, with no sense of display. The advantage, however, is that when emotion is clarified into action or when feeling rises up it’s with a quite unexpected sense of “the rise, the roll, the carol, the creation.”

This book is a hymn to the feminine in all of us as well as to the quiet power of Irish womanhood, recapitulated with great delicacy and apprehension. It's an ugly duckling of a book, a wallflower in the world of contemporary fiction, but it is also that very rare thing, an absolutely believable dream about the all but recent past and the way it lives inside us all, just a step or two away from consciousness. •