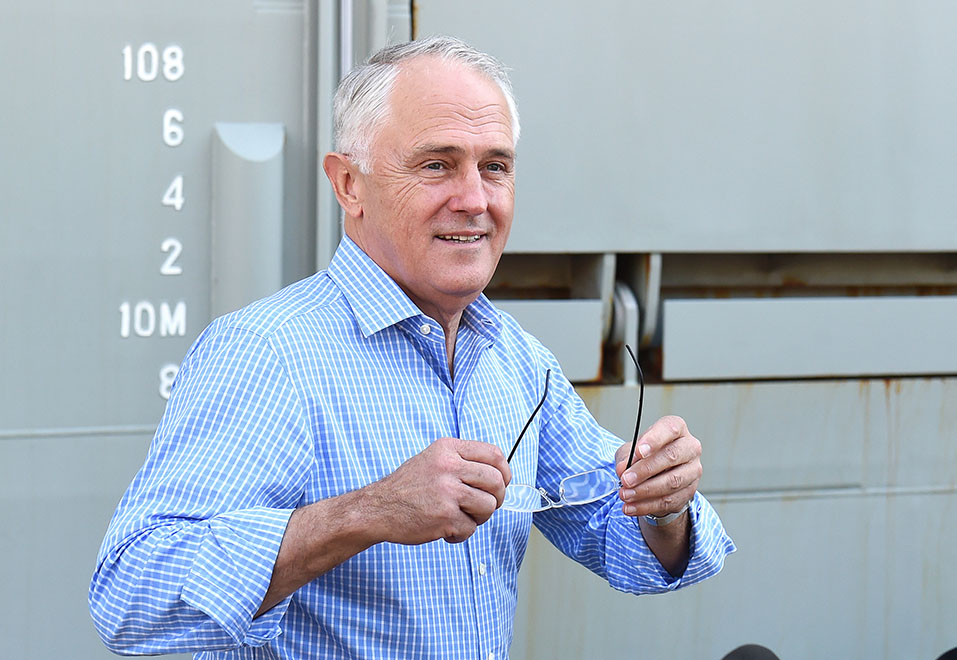

Newspoll has shifted two points in two-party-preferred terms over the past fortnight, putting Labor slightly ahead, at 51–49, for the first time since Malcolm Turnbull became prime minister. Within Australia’s version of the beltway, this has set off several clanging bells.

As a general rule, attempting to identify the drivers of fluctuations in individual opinion polls is a mug’s game. Surveys bob up and down for no real reason, or they’re pushed by deeper underlying dynamics or events from weeks or months ago.

I’ve noted here before that Newspoll’s preference flows are probably overly generous to Labor; today’s primary vote numbers (Coalition on 41, Labor on 36, Greens 11 and others 12) would at most elections produce a likely 50–50 after preferences. And if this were a move from 57 to 55 rather than 51 to 49, no one would be flicking the drama switch.

But sometimes, on rare occasions, poll shifts can reasonably be assigned to particular occurrences, and this is very likely one of them. It’s a good bet that the Coalition’s dip into the red is due to Turnbull’s suddenly announced plan last week to hand back income-taxing powers to the states.

The fact that it died an ignominious death within hours was good for the government. If the premiers and chief ministers had jumped on board, Turnbull and Scott Morrison would now be taking a huge, controversial, complicated and yet-to-be-finalised tax package to the 2016 election.

In policy terms, the prime minister’s suggestion may well be just what’s needed to address vertical fiscal imbalance. If so, then early in the next term would have been the time to throw it open for consideration. The very idea of producing such a scary proposition just months before an election boggles the mind. The dollars involved, the anticipated payslip disruption and the fodder for an opposition scare campaign dwarf the Howard government’s 1997–98 GST adventure.

Labor will now campaign on the Coalition’s secret plan to give taxing powers to the states, and Turnbull will need to deny it. So by kicking this contentedly snoring dog at this particular time, the prime minister has made state income-taxing powers even less likely in the medium term, and will ensure that any such policy joins GST-tinkering as something both parties routinely swear off before every election.

Why on earth did he do it?

Perhaps Malcolm and his confidantes were swayed by the commentators nagging for the Coalition to take a substantial tax plan to the election. They simply must, because, as we have read, Labor has seized the agenda, and if the government doesn’t match it, well, the press gallery will shake its head and write and say unpleasant things about the prime minister and his colleagues. Politicians and their advisers do tend to get caught up in political narratives.

Another related possibility is that party research has found a craving among voters for substance. The punters are asking what Malcolm Turnbull stands for. Where’s the beef?

This outsourcing of strategy to focus groups is usually something associated with the Labor side of politics, but back in 1997 a fear that his government was perceived to be drifting pushed John Howard into his near-fatal GST excursion. So it can happen on that side too.

It has been suggested, tantalisingly, that this was simply a negotiating position for COAG, with little consideration given to wider political ramifications. This is a fascinating possibility. It would be consistent with the brinkmanship and single-mindedness that has characterised much of Turnbull’s professional career. It would mean that he totally subjugated any public political considerations to the demands of the deal-making, which would be just amazing for a political leader.

Still, if we accept that last week’s clanger produced this week’s Newspoll, then this means that, if not for that error, the government would now be comfortably ahead in the polls. And because Turnbull has unloaded this policy, the long-term damage should be minimal and the Coalition remains almost as likely to win the next election as it was this time last week.

Except that events have repercussions. The political class hangs off Newspoll, and this will further embolden Coalition conservatives in their cot-rattling. In February a surprise 50–50 Newspoll was followed within days by the Safe Schools capitulation. What’s next on the agenda?

On the plus side for the government, this might encourage Labor to roll out more bold policy, because it believes its courage drove last week’s debacle – and in the sense that it led to an unforced prime ministerial error, that’s right. But Labor has already unveiled more than is politically wise, and during the campaign will likely be regretting its big-target housing policy.

As Tony Abbott’s final months illustrated, errors heighten insecurity and can produce more blunders. Abbott did dumb things, but they usually involved drawing succour from the party base, with collateral damage in the mainstream. Turnbull’s misjudgement, by contrast, was truly Gillardesque in its provocation of the economic anxieties of the electorate.

The biggest take-out from last week’s fiasco is not its repercussions, but what the event itself says about Turnbull’s political judgement. We now know he is capable of gratuitous, spectacular error. There’s hope for the Labor opposition there. •