A year ago today, Australians were shocked to learn they had re-elected the Coalition government — and with a 1 per cent two-party-preferred swing, no less (although that translated into only one extra seat).

Back then, Scott Morrison and his team ran a disciplined, hip-pocket-focused campaign. For the very opposite, go back to Labor’s 2013 re-election attempt, when Kevin Rudd tried again and again, with on-the-run policymaking, to get a “boost” in the polls that would carry through to election day.

Desperate prime ministers can be tempted to do this kind of thing. John Howard did it in 2007 with his Northern Territory intervention and, twice, by targeting Sudanese refugees.

But last year’s more successful effort was focused on the fundamental equation: the decision voters make at the ballot box. And the message Morrison and his colleagues hammered home was that they were the safer alternative.

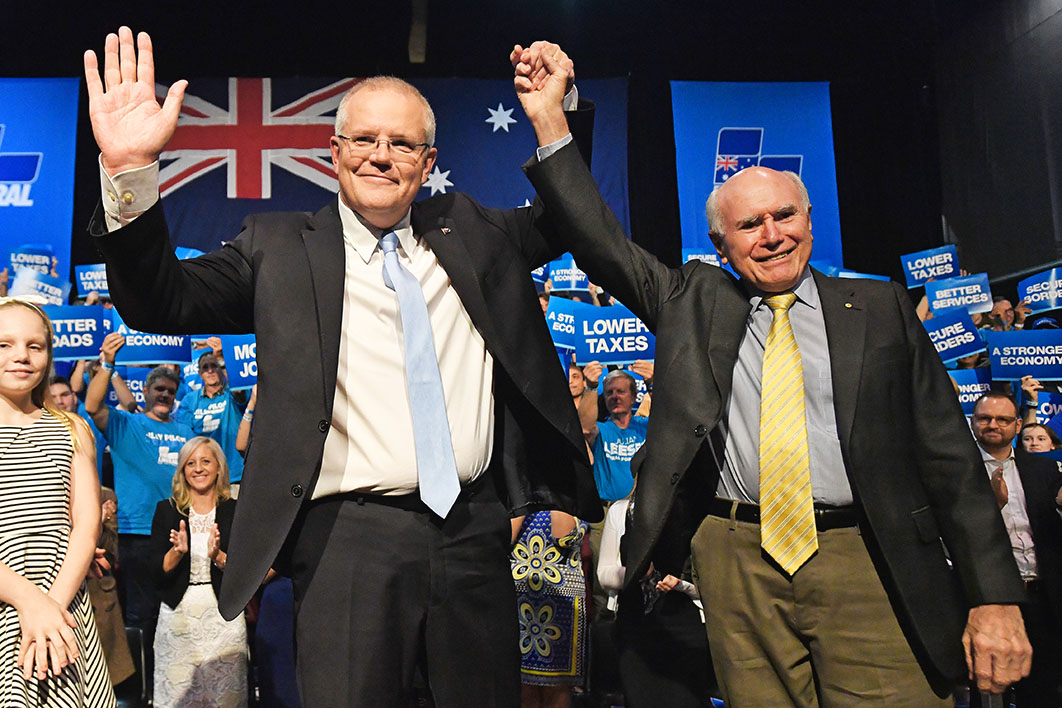

After 18 May 2019, Morrison was God — even better, to some, he was Howard reincarnated. But the more apt comparison is with Paul Keating in 1993. A surprise win transformed Keating into the unbeatable master of caucus — until his comeuppance five months later after a budget no one liked. (Hiking indirect taxes after an election dominated by your opposition to a GST can do that.) Last year Morrison enjoyed seven months of sunshine before an unwise holiday in the Pacific followed by several blundered attempts to reset his public persona.

But that’s all forgotten now. He’s riding high, as are the state and territory leaders. It’s a respite from a long, steady depletion of trust in political parties and governments, assisted by sluggish economies. But while the coronavirus will linger, our leaders’ heightened stature can’t.

The latest federal Newspoll, roughly in line with other surveys, has the prime minister’s personal ratings still very high, with voting-intention figures putting the Coalition on 43 per cent and Labor on 35. If this were Britain or Canada, with first-past-the-post voting, such figures would point to a landslide win for the government. As it is, estimated preference flows put the Coalition just ahead, 51–49, because around 80 per cent of Greens support (which is 10 per cent in this poll) will end up in Labor’s two-party-preferred pile.

What do polls like this mean? Very little. Given Morrison’s personal ratings, it’s interesting that the government isn’t further ahead. But the “if an election were held today” scenario is even more ludicrous than usual. We’re in a crisis and political attitudes are on hold.

Overall, the 2022 election result remains as it was last year: unpredictable, but with Labor the likely victors. Re-election is difficult for nine-year-old governments. The economy wasn’t great before the current crisis, which has added to the likelihood of the unexpected (and unforeseeable), in any direction.

The biggest potential strain lies within the Coalition. If it were in opposition it could complain about Labor’s reckless spending, but governing bestows certain responsibilities. Still, a substantial section of the government’s support base is grumpy about the measures taken, partly because they have internalised the propaganda about the Rudd government’s response to the global financial crisis: you can’t spend your way out of trouble. Now this centre-right government is doing the same, but on steroids. There’s also the related backlash against the health restrictions, which often veers into voodoo analysis, mixing up cause and effect (namely, “all these restrictions and for what, just a few deaths?”).

Naturally enough, the rushed-out spending has its anomalies. If Labor were in power we would have a good idea how it would play out politically in coming years (not well for them) but the electorate gives the Coalition more leeway on fiscal behaviour.

Which brings us back to the friendly fire. For the time being, Morrison’s heightened community standing inoculates him against internal mischief. But that’ll be gone soon enough, probably by the end of the year.

Then intra-party machinations might get interesting again. •