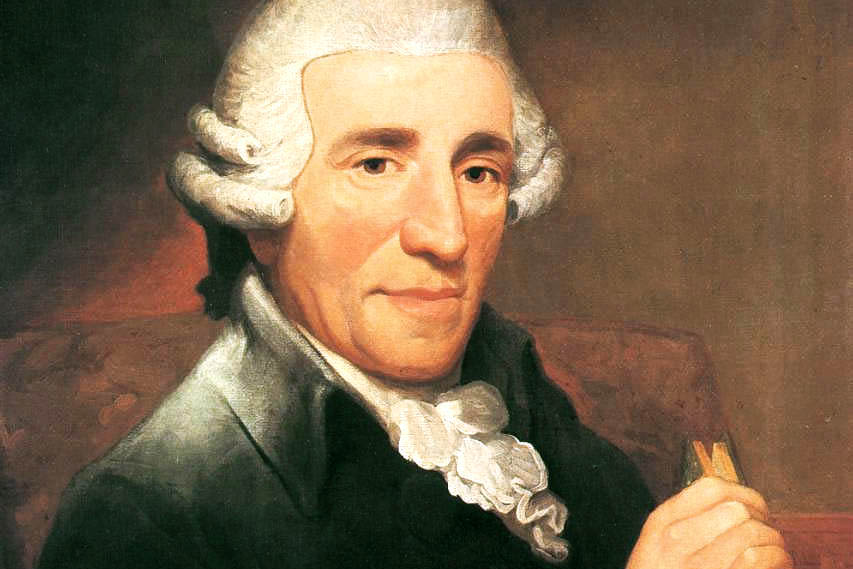

The late composer Peter Sculthorpe once told me he had no interest in listening to classical composers such as Haydn or Mozart. Now, Peter sometimes said things like this for effect, and on this occasion he evidently enjoyed my surprise and mild discomfiture. But even if the declaration was to some degree a pose, he obviously meant it. I think it was the powdered wigs he couldn’t get past. Stylistically, this was music of its time and place – mid- to late-eighteenth-century Austria – and it didn’t speak to him.

When performers play old music at the expense of new, as most classical musicians do most of the time, I find myself tempted to express similar sentiments. But fundamentally I disagree with Sculthorpe (as I told him), because I think great art transcends the time and place of its making. And a good performance of old music makes it new again.

For the past few months, I have been listening with undiluted pleasure to the symphonies of Haydn. For the first time, a set of all 107 is available played on instruments of the period (or copies of them). Most of the recordings are by Christopher Hogwood with the Academy of Ancient Music and Frans Brüggen with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century or the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Each conductor recorded a large number of these symphonies between 1984 and 2000.

Both projects ran out of money, but between them they nearly finished the job. Brüggen recorded the later symphonies, including those often rather grand works commissioned for public concerts in Paris and London in the 1780s and 90s, and the tumultuous Sturm und Drang (“storm and stress”) symphonies from the late 1760s and early 70s; Hogwood recorded pretty much everything up to and including the brilliant, witty works of the mid to late 1770s. It remained only for Decca to invite Ottavio Dantone to record the four missing symphonies (Nos 78–81) with Accademia Byzantina and then box up the thirty-five CDs.

Perhaps the first thing to remark upon is that matter of style. The truth is that these works are hardly all of a piece. Spanning nearly half a century, they range from the sombre to the lighthearted, the dramatic to the formal, the intimate to the celebratory. That’s one aspect of it; the other (this is where the powdered wigs come in) is the overarching style that Haydn and Mozart shared with other Viennese composers of the late eighteenth century, including the young Beethoven. Well, if you keep listening, it disappears. It’s the same as with Jane Austen or Charles Dickens. When you read their opening pages, you are at first aware that these writers’ use of language isn’t your own. But the more familiar the writing style becomes, the more it resembles George Orwell’s “windowpane,” which you no longer see, but see through. You come suddenly face to face with Austen’s and Dickens’s characters.

As you grow familiar with the style of Haydn’s symphonies – which is a matter of repeated listening – you cease to hear it at all. Instead, you are astonished by the twists and turns his music takes, the structural daring; because you have absorbed the style, you notice how often he breaks his own rules, which is a surprising amount of the time. For most of his career, Haydn was a “house officer” in the employ of three generations of Esterházy princes. Based at the Esterháza palace, about 120 kilometres south of Vienna, this liveried servant wrote the majority of his symphonies for the court orchestra, when he wasn’t writing operas, string quartets and 126 baryton trios for Prince Nikolaus I. Haydn might have been told what to write – left entirely to his own devices, he would hardly have opted to write all those trios for a novelty instrument – but exactly how he went about his work was up to him.

Wagner would later dismiss Haydn as an “imperial lackey,” but perhaps he was jealous, given his own less satisfactory relationship with a patron in the form of the mad Bavarian king, Ludwig II. In fact, Haydn’s isolation and workload were the making of him. Haydn was one of music’s great experimenters, Esterháza and its orchestra his laboratory. “I was set apart from the world,” he said. “There was no one nearby to divert me from my course, and so I was obliged to be original.”

That originality is everywhere in these symphonies. There is sonic experimentation, from a pair of reverent cors anglais gliding through the slow first movement of Symphony No. 22, to four cavorting hunting horns at the start and end of No. 31; there is the wide embrace of folkloric elements (Haydn’s orchestra impersonating bagpipes and hurdy-gurdies); there is structural experimentation everywhere as the symphonic form expands and contracts and expands again; and there are avant-garde shocks, for instance when the finale of No. 60 grinds to a halt for the string players loudly to retune their instruments. Surprises abound, and not least, in such a vast body of work, the surprise of discovering a symphony you’d previously overlooked. The other day I heard No. 70 in D, I think for the first time. I don’t know how I’d missed it before, but it’s a wonderful piece and its first shock comes in bar two: a big, fat accent on the last beat of the bar that, 250 years after its composition, caused this listener to wonder for a moment whether the music was in triple time or duple.

But what of the recordings’ use of historical instruments? Isn’t there here, at least, an element of dressing up in powdered wigs? I suppose you’d have to say there is. But that is not what one takes away from listening to these discs. As is nearly always the case with good playing on period instruments, the main effect is to modernise the music. There is something about the slightly fatter oboes and thinner trumpets, the hard timpani sticks on calf skin, the gut strings with sparingly applied vibrato that clarifies the orchestral texture and balance, and communicates the music more directly. Everything is bolder, and that boldness – which is all the composer’s doing – can still stir us or move us or take us by surprise. •