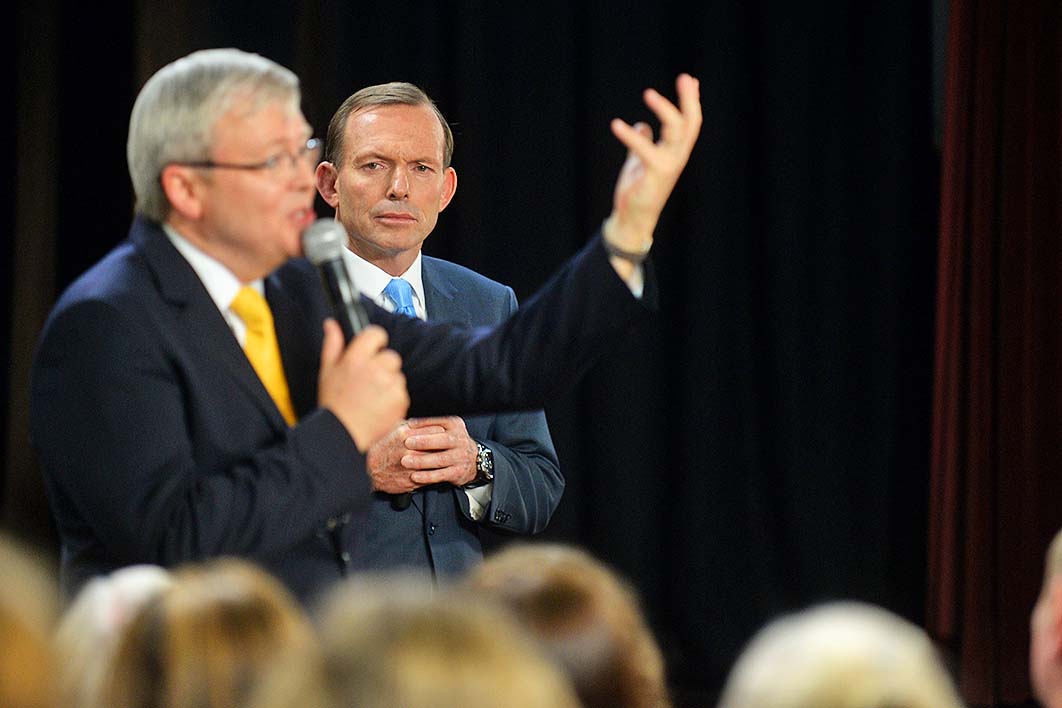

With Tony Abbott’s ferocious payback tour showing no signs of winding down, his behaviour is increasingly compared to former prime minister Kevin Rudd’s conduct during his 2010–13 wilderness years. Similarities there are, but they are vastly outweighed by the differences.

Both men took their party to office at the ballot box, but under contrasting circumstances. Rudd’s feat was far less impressive: he simply slipped into the leadership when Labor was already generally ahead in the polls and headed for likely victory.

Abbott cut his own path to the Lodge. Like Rudd, he was elevated less than a year before an election, and hence enjoyed guaranteed tenure – though in Abbott’s case the Coalition was way behind in the polls and a win appeared unlikely. Abbott was also saddled with his own baggage: he was widely perceived in the community as an overly religious oddity, respected – perhaps – for sticking with his anti-abortion convictions but with little else going for him.

He had already published his book Battlelines, though, in an attempt to flesh out that public persona, and as leader he proved an adept opportunist. References to that which had been “this generation’s legacy of unutterable shame” (the rate of abortions) rarely passed his lips again, and by opposing the Rudd government’s carbon pollution reduction scheme he got into Labor’s head – which turned out to be a breathtakingly easy break-and-enter.

The following year’s drama flowed from that decision. Kevin’s backflip, Labor’s leadership change, the rush to the election, Julia Gillard’s mad incumbency-free re-election strategy – all generated the hitherto unthinkable, Tony Abbott as an acceptable candidate for prime minister. After taking the Coalition to the brink of victory in 2010, his second accomplishment was remaining opposition leader for three more years.

This he achieved by, yes, relentlessly attacking the Gillard government (he was desperate for an early election) but fundamentally by winning thumping voting-intention leads in the published polls. But he was never held in any kind of regard by most voters, and after Rudd’s return in June 2013 his position began to look shaky. Kevin obliged by calling the election quickly, motivated in part by fear of a return to the now-popular Malcolm Turnbull.

The two men’s personalities could hardly be more different. Abbott is, by all accounts, genial and considerate in person (like Julia Gillard). Rudd, on the other hand, is often cranky, sometimes bullying, with a curious need to put others in their place. He is highly intelligent, a policy wonk, and was across all portfolio areas. Abbott, not to put too fine a point on it, is none of these; philosophical musings are more his forte.

For a time, Rudd attracted the highest recorded approval ratings for an opposition leader, and then for a prime minister. The only records Abbott was in contention for were at the other end of the scale.

The dumping of Rudd in June 2010 is seen, close to unanimously, as an act of monumental political stupidity. The government had briefly dipped below 50 per cent two-party-preferred support in the polls, and at the time of the leadership change had been ahead in Newspoll for two fortnights in a row. If you accept (as I do) the counterfactual of a comfortable Labor victory under Rudd in 2010, the Abbott experiment could have been quickly terminated if Labor hadn’t panicked.

While Malcolm Turnbull might have disappointed as prime minister, the Liberals’ September 2015 leadership change will never be widely perceived as a blunder. It was more like Rudd’s 2013 comeback, which was greeted with an almost audible sigh of relief in voterland. Turnbull remains streets ahead of Abbott in head-to-head polling of preferred Liberal leader.

While Rudd enjoyed high esteem in the community during his exile, Abbott remains toxic. Yet he is adored by a highly ideological section of Liberal supporters, the self-appointed “base.” In Labor’s leadership wars, Labor’s own base remained firmly behind Gillard. Rudd was like Turnbull, seen by true believers as a carpetbagger; as Wayne Swan once put it, in characteristic prose, he “lacks Labor values.”

So Rudd’s campaign to retake the top job was directed not at caucus but at the general public, whose role it was to earbash their local Labor MPs. Abbott also bypasses the party room, but speaks to a small minority of Australians, the roughly 10 per cent of the voting population that tells pollsters he should lead the Liberal Party. At the elite level, the Abbott Show is strictly for the Hadley, Jones, Sky News (evening editions) crew and a handful of News Corp sentimentalists.

Any leadership aspirant must offer electoral salvation to his or her party. Rudd promised a popular and reauthorised leadership, generating a boost in the polls that would carry the party to victory (or at least “save the furniture”). Abbott pledges a major shift to the political right that he believes will remake the political landscape. Conceptually, such a strategy shouldn’t necessarily be dismissed, but the specifics here – the detested Abbott at the helm, voters reinvented as coal-adoring, renewables-hating, 18C-fixed IPA card-carriers – sit in the realm of science fiction.

After he lost the February 2012 leadership spill, Rudd warned (in not so many words) the party not to replace Gillard with anyone other than him. Abbott, by contrast, gives the impression that he would accept the consolation prize of another conservative (read “Peter Dutton”) as prime minister.

The Liberals will likely tear Turnbull down (or he will come up with a reason to bow out) by year’s end, but the choice before them of replacement is invidious. The candidate who is streets ahead as his most-wanted replacement, Julie Bishop, will be bypassed, not because she’s a woman but because she’s seen as “moderate,” and it’s a right-winger’s turn again, and because she’s too close to Turnbull and was insufficiently loyal to Abbott in September 2015.

The most likely candidates are Dutton – another Sky News hit for whom even fewer Australians clamour – or, perhaps, Scott Morrison (whom Tony has not yet forgiven for his 2016 desertion).

Bill Shorten, meanwhile, enjoys enhanced security thanks to rules put in place by none other than Rudd. The view must be wonderful from there. •