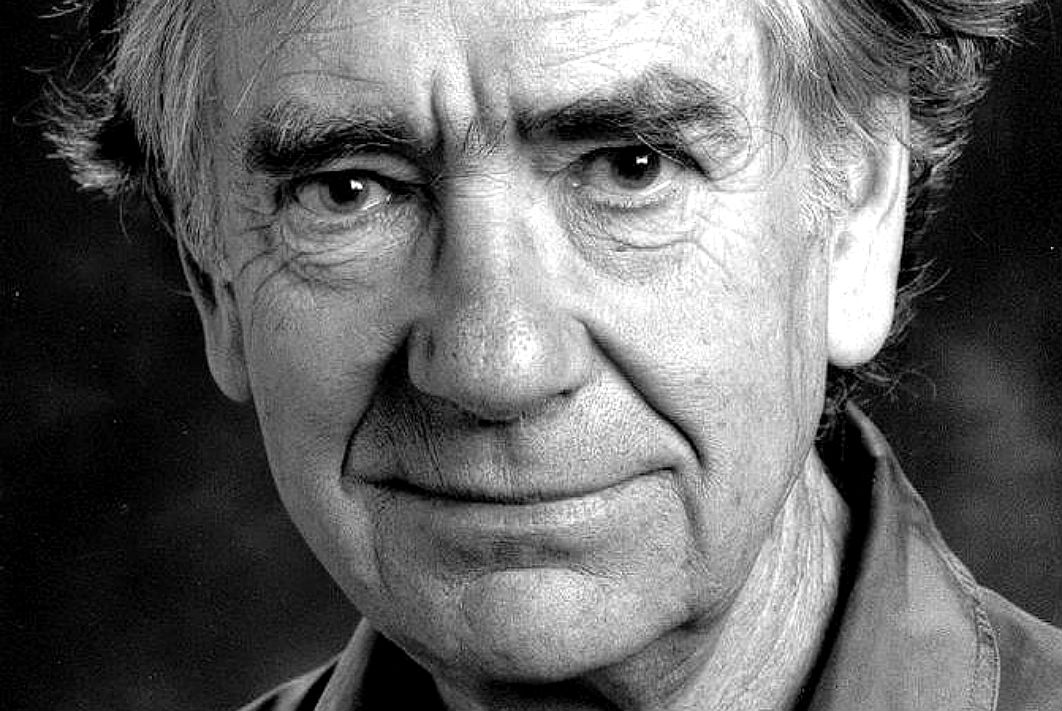

When I visited Ken Inglis early last month, a few weeks before he died, I found him engrossed in the day’s edition of the Sunday Age. It was eighty years since he’d begun reading newspapers as a schoolboy in the northern Melbourne suburb of Regent, and since then he’d become one of Australia’s most highly and warmly regarded historians. But his passion for the press — his fascination with the way it recorded “the history of the present,” as the historian Timothy Garton Ash calls it — was undiminished. And not just newspapers — on the table beside his bed were copies of the New Yorker, the magazine that helped shape his style and fuel his curiosity.

Ken will be remembered most for his major books — The Stuart Case, his forensic study of the prosecution of Max Stuart; The Australian Colonists: A Social History of the Period from 1788 to 1870; his two-volume history of the ABC; and his award-winning exploration of Australian war memorials, Sacred Places — and for two great collaborations, the eleven-volume Australians: A Historical Library and a forthcoming two-volume account, with Semus Spark and Jay Winter, of the men brought forcibly to Australia during the second world war on board the Dunera.

There, and in a great number of journal articles, conference papers, radio talks and seminars, he examined how we think about war and explored our national identity and customs, our changing religious beliefs and observances, the impact of migration, the foibles of the media and much else. His 1965 Meanjin article, “The Anzac Tradition,” for instance, was “the first serious modern discussion of Anzac and the digger legend,” wrote Geoffrey Serle. “Ken was asking his hearers to set aside their prejudices,” adds Graeme Davison, “and to consider whether the seemingly ‘meaningless’ rites of Anzac did not have a meaning after all.”

That setting aside of prejudices was very much a feature of Ken’s work, and carried over into his engagement with newspapers and magazines — as contributor, encourager and critic. In Inside Story’s case, the help came in the form of much-valued advice, including his inspired suggestion in February 2009 that Tom Griffiths write for us about the Black Saturday fires (an essay that went on to win that year’s Alfred Deakin Award).

Journalism had been his “only boyhood ambition,” he wrote when he was in his late sixties, an ambition “formed after reading Isobel Ann Shead’s novels Sandy, about a lad who became a newspaper reporter, and Mike, about another who became a radio man.” But the times — this was near the end of the second world war — turned out to be against him. Young Ken, the sixteen-year-old editor of Melbourne High School’s fortnightly newspaper, the Sentinel, called on the editor of the Age, Harold Campbell, who told him that too many experienced journalists were about to return from the war expecting their jobs back. But the ambition lived on, and found its perfect outlet in the late 1950s.

Ken’s capacity to do two things very well — to identify the shortcomings of the press and to write superior journalism of his own — first became clear in his work for Tom Fitzgerald’s ground-breaking fortnightly magazine, Nation (1958–72). Ken had written for newspapers before, and he had also been an occasional contributor to Harold Levien’s magazine, Voice (1952–56), the first serious attempt to produce an Australian version of the New Statesman. But Nation was a revelation for contributors and readers alike — topical, on-time, sharply written, well-informed and, above all, independent — and Ken, along with Sylvia Lawson and others, was in its pages from the first edition.

Ken’s style perfectly suited the magazine. As his colleague at the University of Adelaide during the early Nation years, Robert Dare, said at a colloquium on Ken’s work late last year:

His interest was less in voicing disapproval than in observing the rituals, frequently arcane, usually ancient but occasionally in the process of formation, that structure our lives. That required him to be sensitive to idiosyncrasy and self-delusion, paradox and contradiction, change and continuity, all of which have something to tell us about the peculiarities of our culture — and make great copy to boot. Through the pages of Nation he found a way to bring the methods of the historian to an understanding of how we live now.

Ken wrote on an enormous range of topics for the magazine, from the Australian tour by the radical American singer-songwriter Tom Lehrer to a Jehovah’s Witness rally in Adelaide. But mostly he wrote about the press, and what distinguished these pieces from other reporting about newspapers and broadcasting was his careful reading of their content, including their visual styles.

Fitzgerald was more than happy to give space to this kind of scrutiny: his ambition with Nation was to show the broadsheet papers, one of which he worked for, how to better serve their readers. The two men — tall, lanky, slightly dishevelled Ken, with his fine head of hair, and the short, neatly dressed, balding Tom, temperamentally so alike — made quite a pair.

All the characteristic elements are there in Ken’s first piece on the press, which describes the rivalry between the establishment Adelaide Advertiser and young Rupert Murdoch’s afternoon paper, the News. “The News and the Advertiser usually ignore each other’s existence, though they are not inflexible about it,” he writes drily, before describing an early instance of what would become Murdoch’s modus operandi: boosting his own paper by relentlessly attacking the opposition paper’s news as stale. “The attack rested on the undeniable fact that the Advertiser comes out in the morning and the reasonable assumption that a lot of things happen in the world which enable evening papers to report them first.”

Ken’s scrutiny of the Adelaide papers became even more pointed in a series of articles about the police’s mistreatment of Max Stuart, an Aboriginal man accused of a brutal murder. One of Ken’s pieces about the affair attracted the attention of a Sydney Morning Herald journalist, who flew to Adelaide, interviewed a supporter of Stuart’s, Father Thomas Dixon, and turned the case into national issue.

Ken’s technique is on display in two long pieces he wrote for Nation after the launch of Rupert Murdoch’s boldest new project, the Australian, in mid 1964. The new paper, he wrote a few days after its launch, “is, first of all, a clean and handsome thing to look at. Not all the news pages have the ‘elegant appearance’ we had been led to hope for; but compared with those of every other Australian newspaper they are, as promised, ‘uncluttered.’” But the paper’s prose was less elegant: “Contributions by such writers as Robin Boyd, Jock Marshall, Kenneth Hince and Edgar Waters read as if the layout were designed for them; some other pieces, signed and unsigned, sit there less happily.” Even more worryingly, most of page three was devoted to an extended gossip column with a horoscope. Rupert Murdoch’s contradictory impulses, and his fear of failure, were on vivid display.

“On Saturdays,” Ken wrote in a second piece, four months later,

it seems to me quite clearly the best paper we have. During the week, if I lived in Brisbane or Adelaide or Hobart I would feel a daily surge of gratitude to Mr Murdoch for giving me an alternative to the stifling parochialism and ugly layout of my morning paper… If I lived in Sydney or Melbourne or Perth, my estimate of the Australian would depend on how it happened to be performing on any particular day; for its quality as a provider of news varies much more than its readers were led to expect.

Between pieces for the magazine, Ken also had a chance to do the kind of journalism he’d had in mind when he’d called on the editor of the Age. In 1965 he accompanied a pilgrimage of old diggers to Gallipoli for the fiftieth anniversary of the Anzac landing, half his fare paid by his employer, the Australian National University, and half by the Canberra Times. He wrote seven richly reported despatches from the journey, which Inside Story published as an ebook another fifty years later, in April 2015. He later confided that he had been “enraptured” to be carrying a card authorising him to send cables via London to Sydney. He would write in a similar register in several of his books, including his memorable description of his visit to Central Australia researching the extended postscript for Black Inc.’s reissue of The Stuart Case.

Living in Papua New Guinea in the late 1960s and the early 70s with his wife, the writer Amirah Inglis, and their family, he wrote for the Canberra Times about that country’s journey to independence. (Nation already had a correspondent, Hank Nelson, in Port Moresby.) After Nation, Ken continued to write, though less frequently, for newspapers and magazines. Ten years later, a new fortnightly (later a monthly), Australian Society, was launched, and after I became editor in 1985 Ken was a contributor of occasional pieces, including a forensic examination of the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of the Australian, a defence of Radio Australia, and an account of a slightly hair-raising visit to Moscow during the early Yeltsin era (“Will he take all my dollars, and leave my body to be covered by snow under the birches?”). One of his Australian Society pieces was about Nation, and in that same year, 1989, he published a book, part-history, part-anthology, about Nation and its creators.

Ken was a deft, careful and generous writer whose prose lit up any magazine or newspaper — or book or journal — it appeared in. He was also great company, the possessor of a prodigious memory and an insatiable curiosity (clichés that, though accurate, would no doubt bring a smile to his face), and a source of wise counsel. As Graeme Davison wrote in a recent edition of History Australia, his “influence is not to be found in the sum of his scholarly contributions — or not in those alone — but in his influence upon others, and the unfailing generosity of spirit and acuity of mind that he has imparted to our professional and national life.” ●

The location of Ken Inglis’s childhood home, incorrectedly given as Preston, has been changed to Regent.