After the housing boom came the bust. It’s been the main story in Sydney and Melbourne for a year or more, in the rest of Australia more recently. But a dramatic seven days has firmed up the view that we will soon be reversing course: prices will hit bottom and start heading upwards.

The Morrison government’s election win killed Labor’s plan to shut the gate on negative gearing and reduce tax breaks for capital gains. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority lowered the excessive safety margins it required on home loans as insurance against rate rises. And Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe made it very clear that the bank is about to cut interest rates.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver now forecasts that prices will bottom out by the end of 2019, not much below current prices. That would allay fears of further price falls dragging down the economy. But it would also end the progress made on housing affordability, which has allowed first homebuyers back into the market.

The key question is: what comes next? What do the Morrison government and the Reserve Bank want the next stage of the housing market to look like?

Will they aim to create the conditions for another boom in housing prices? Or will they aim to create stability in house prices — just as the Reserve Bank aims for price stability in more humdrum purchases?

And as the global and Australian economies lose momentum, could the housing market once again be conscripted to lead the fight against the threat of recession — with housing affordability sacrificed as collateral damage?

Welcome back to government, Mr Morrison. There are a few challenges waiting for you.

The housing market is one that Scott Morrison knows a lot about: he used to work there, and he made it a central issue in the election campaign. And now it’s his opportunity, and responsibility, to set the goals for what happens next.

The central issue is: do we want to return to the way the housing market has developed in the past forty years, and continue those trends into the future? Or do we want to end this long period of high inflation in housing prices, declining affordability, and declining home ownership?

In 1980, the median home cost less than three years of median household income. Home ownership was not universal, but it was close. The 1981 census found 75 per cent home ownership among thirty-five- to forty-four-year-olds, and 61 per cent even among twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-olds. If you aspired to own your own home, you usually could.

Then housing prices took off.

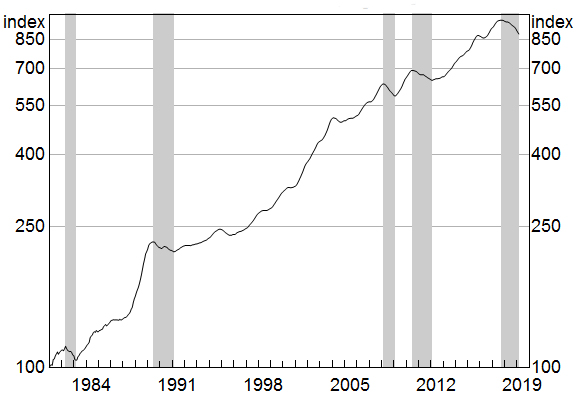

We had a boom from 1983 to the end of 1985, a pause when Labor ended tax breaks for negative gearing, then back to boom when it restored those tax breaks. Prices had roughly doubled by the time the boom ended in 1989, when the Reserve Bank lifted mortgage rates to 17 per cent.

National housing prices 1980–2019

December 1980 = 100. Logarithmic scale

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia chart using CoreLogic data

There was a small correction, and seven years of roughly stable markets allowed incomes to catch up a bit. Then prices took off again in 1997, in a boom that essentially ran until rising interest rates choked it at the end of 2007. By then the median house cost two and a half times as much as it had in 1996, and five times as much as it had in 1986.

A big correction was needed: a long period of slowly declining or stable prices, to allow household incomes to catch up. Instead, we were hit by the global financial crisis. Interest rates went down, so housing prices went up. The Reserve soon slammed on the brake, raising interest rates by far more than the economy required, and prices edged down. But in 2012 a crucial policy choice intervened.

The mining investment boom had seen the Australian dollar soar to levels that made Australian industries across the board globally uncompetitive. After the boom would come a bust, and some of us noted that every time mining investment had gone bust in the postwar era, the economy had gone bust with it. This was a colossal boom compared with any before it. We were facing a colossal bust.

The Reserve got the message.

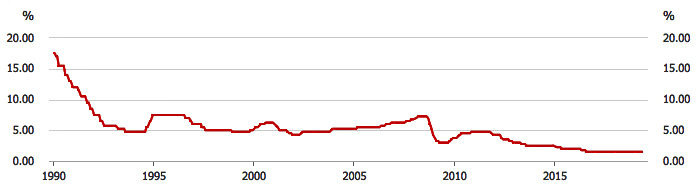

It repealed every one of its interest rate hikes, and then some. In fifteen months during 2012–13 it gave us the equivalent of seven interest rate cuts, taking the cash rate to a record low of 2.5 per cent. Two more cuts followed in 2015, and another two in 2016.

Reserve Bank cash rate, 1990–2018

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

These interest rate cuts had nothing to do with the 2 to 3 per cent inflation target. They aimed at stopping the economy going into recession as the mining boom turned to bust. And the housing market was to be its saviour.

The mining boom peaked in September 2012. In the next four years, the volume of housing construction and property transfers shot up by 35 per cent. With their links to manufacturing, transport, professional services and so on, they largely offset the fall in mining construction.

Alas, this created another boom in home prices. The Bureau of Statistics estimates that Sydney prices shot up 80 per cent and Melbourne 57 per cent. Housing affordability became collateral damage in the war against recession. As the Reserve Bank graph shows, national housing prices by December 2017 were almost ten times higher than in December 1982.

Household incomes had not kept pace. Buying a home now required six or seven years of the median household income, not two or three. The 2016 census found home ownership rates had slumped from 75 to 62 per cent among thirty-five- to forty-four-year-olds, and from 61 to 45 per cent among twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-olds. Young buyers could not compete with rental investors enjoying tax breaks on rental losses and capital gains. For a while, most of the money banks lent for housing purchases went to investors, not owner-occupiers. Sir Robert Menzies would have turned in his grave.

Another long correction was needed. And a year and a half of falling prices has made some progress in improving affordability. Housing analyst CoreLogic reports that median prices have fallen 15 per cent in Sydney, 11 per cent in Melbourne, and 10 per cent across capital cities. Its head of research, Tim Lawless, noted that the pace of decline has slowed in 2019, easing fears of a hard landing in which investors might panic and rush for the exits.

Some say Labor’s plan to shut off tax breaks on negative gearing for new purchases was a factor in the price fall. Certainly, the real benefit of that plan was that over the long term it would weaken the incentive for investors to jump in, and hence reduce the frequency and size of future booms, creating a period of price stability in which renters could again afford to become first homebuyers.

Lowe implied in his answers to questions on Wednesday that the looming rate cuts will be aimed not at the housing markets but at stimulating the economy in general. The Reserve Bank is sufficiently worried by the trends in global markets and at home that it is prepared to use up scarce ammo to try to boost activity.

Morrison and treasurer Josh Frydenberg also did their bit for the economy in the budget, with a tax break offering up to $1080 to low- and middle-income earners, and a $284 grant to people on welfare. Economist Chris Richardson of Deloitte estimates that this is equivalent to a 2 per cent rise in after-tax wages: significant at a time like this.

But the long-term issues must be faced. If the PM and his team want to keep negative gearing, do they want it to play as big a role as in the past?

In the four years to 2016–17, the tax office notes that a quarter of the growth in negatively geared taxpayers was among people who owned three or more investment properties. Morrison as treasurer tried to cap this, but was blocked by opposition from MPs and senators, one of whom owned fifty properties. To revive his plan would be a small step, but a useful one that sends a message.

And the message from both the government and the banks needs to be: we don’t want any more housing booms. We want to make homes affordable for ordinary Australians. •