IN ITS 28 May edition the Economist carried a long feature about Australia, praising our resilient economy, criticising the quality of our political discourse, and highlighting our social egalitarianism. “The Evolving Platypus: A Distinct Society, Perhaps Becoming Less So,” was the magazine’s summary of how we do things here.

The feature referred to an article in Policy, the journal of the Centre for Independent Studies, by David Alexander, a former senior adviser to Peter Costello. Under the title “Free and Fair: How Australia’s Low-Tax Egalitarianism Confounds the World,” Alexander argues that Australia offers a genuine alternative to both the low-spending but high-inequality United States and the high-taxing but egalitarian countries of Northern Europe. This “unique form of low-taxing egalitarianism,” he concludes, “is both more successful and more sustainable than other models.”

Is this characterisation of Australia’s social protection system accurate? Alexander presents a wide range of evidence to support these arguments, and it is not surprising that I agree with much of it, since one of his sources is a paper I wrote for a conference during the Henry Review of Australia’s tax system.

The most recent data on social spending in OECD countries shows that in 2007, the year before the global financial crisis, Australia spent 16 per cent of GDP on cash benefits (including pensions and unemployment payments, healthcare and community services) compared to an OECD average of just over 19 per cent. We actually spent a little less than the United States and Japan, and the only countries that spent substantially less than we did were lower-income countries like Mexico, Chile, Turkey and Korea.

In most rich countries, the welfare state is the largest single component of public spending and therefore the main determinant of how much tax income needs to be collected. About half of all the taxes collected in Australia are directed to social spending, but because we spend less than average we also have lower taxes than average. With taxes at about 27 per cent of GDP in 2008 compared to an OECD average of close to 35 per cent, Australia is the sixth lowest-taxing country in the OECD.

So it’s fair to say that we are a relatively low-taxing country compared to other rich nations, and to a significant extent this is because we have lower levels of welfare spending. But is this spending particularly egalitarian and are our taxes progressive?

To answer these questions, we need to look at how social spending and taxation is distributed across income groups. And to do that, the most up-to-date comparisons, using 2005 data, are in a 2008 OECD study, Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. (Although the data is six years old, the ways in which benefits and taxes are distributed tends not to change significantly over short periods of time, as was confirmed by an analysis prepared for the OECD Ministerial Meeting on Social Policy in May this year.)

It’s important to remember that the Australian social security system differs markedly from those in other OECD countries. In Europe, the United States and Japan, social security is financed by contributions from employers and employees, with benefits related to past earnings; this means that higher-income workers receive more generous benefits if they become unemployed or disabled or when they retire. By contrast, Australia’s flat-rate payments are financed from general taxation revenue, and there are no separate social security contributions; benefits are also income-tested or asset-tested, so payments reduce as other resources increase. The rationale for this approach is that it reduces poverty more efficiently by concentrating the available resources on the poor (“helping those most in need”) and minimises adverse incentives by limiting the overall level of spending and taxes.

Economist Nicholas Barr from the London School of Economics has pointed out that the main objective of social security systems in most countries is to provide insurance against risks like unemployment, disability and sickness, and to redistribute income across the life cycle, either to periods when individuals have greater needs (for example, when there are children in the household) or to periods when they would otherwise have lower incomes (such as in retirement). Barr describes this as the “piggy-bank objective.”

A second objective of the welfare state can be described as “taking from the rich to give to the poor” – or what Barr calls the “Robin Hood” motive – and Australia is the strongest example of a country emphasising this approach. Our system relies more heavily on income-testing and directs a higher share of benefits to lower-income groups than any other country in the OECD (and probably in the world). The poorest 20 per cent of the population receives nearly 42 per cent of all the money spent on social security; the richest 20 per cent receives only around 3 per cent. As a result, the poorest fifth receives twelve times as much in social benefits as the richest fifth, while in the United States the poorest get about one and a half times as much as the richest. At the furthest extreme are countries like Greece, where the rich are paid twice as much in benefits as the poorest 20 per cent, and Mexico and Turkey, where the rich receive five to ten times as much as the poor.

Because of these design features, Australia has the most “target efficient” system of social security benefits of any OECD country. For each dollar of spending on benefits our system reduces income inequality by about 50 per cent more than the United States, Denmark or Norway, twice as much as Korea, two and a half times as much as Japan or Italy, and three times as much as France.

Other countries that are similar to Australia in this regard include New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Ireland, and also Denmark and Finland. In fact, nearly all of the high-spending Scandinavian welfare states target to the poor more than does the United States.

Australia also has one of the most progressive systems of income taxes of any OECD country and, like our social benefit system, our income taxes are the most “efficient” at reducing inequality of any rich country. It is important to note that the progressivity of taxes in Australia is not a result of high taxes on the rich; rather, it’s due to the fact that lower-income groups in Australia pay much lower taxes than similar income groups in other countries (with the exception of the United States and Ireland).

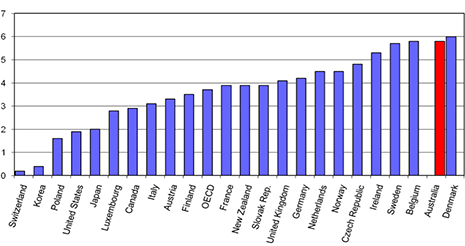

The extent to which the Australian welfare state redistributes to the poor is determined by the interactions between the tax and social security systems, both in terms of the size of taxes collected and benefits paid and the distribution of these taxes and benefits. The chart shows an estimate of “net redistribution” to the poorest 20 per cent of the population in 2005. This is calculated by estimating the level of spending on social security benefits as a percentage of household disposable income and then taking account of how much of this goes to the poorest fifth. The same procedure is used to calculate how much tax is paid by people in that group, which is then subtracted from the benefits received to give “net redistribution to the poor.”

Net redistribution to the poor, 2005

Benefits after taxes received by poorest 20 per cent of households as a percentage of household disposable income

The chart shows that there are large differences in how countries redistribute income to low-income households, ranging from more than 5 per cent of household disposable income in Australia, Belgium, Denmark and Sweden, to around 2 per cent in Japan, Poland and the United States and less than 0.5 per cent in Switzerland and Korea. Nordic countries transfer large amounts of gross benefits to low-income people but also levy a significant amount in taxes from them; conversely, most English-speaking countries pay less generous benefits to the lowest-income households but partly offset this by levying lower taxes on them.

As a result, even though Australia spends below the OECD average on social security benefits, the distribution of benefits is so progressive, and the level of taxes paid by the poor is so low, that Australia redistributes more to the poorest 20 per cent of the population than any other OECD country except Denmark (which spends about 80 per cent more than Australia).

These figures suggest that in important respects the debate over Australia’s welfare state is misconceived. Following the federal budget earlier this year, for example, the issue of “middle-class welfare” attracted considerable media attention. But the OECD data shows that Australia actually has the lowest level of middle-class welfare of any OECD country, a position it has consistently held for at least the past thirty years. Organisations such as the Centre for Independent Studies have also argued that the Australian welfare state is marked by a high level of inefficient and wasteful “churning,” meaning that many people who use welfare state benefits and services finance most or all of what they receive through the taxes they pay themselves. But the OECD data shows that Australia has the lowest level of churning of any OECD country except Korea – and Korea only has lower churning because it has very little at all in the way of welfare payments. Claims by the Institute of Public Affairs that the main beneficiaries of the welfare state are the middle-class bureaucrats who administer the system are equally misleading.

While our social security system has a lot of strengths, this certainly does not mean that there are not real shortcomings to deal with, including the inadequacy of unemployment benefits and rental assistance. The fact that poor Australians get higher benefits than many poor people in European countries or the United States doesn’t actually help them pay their bills. It is always possible to be more efficient, and every year governments go through the laborious process of incrementally adjusting our benefit system to try to produce better outcomes. These changes often look like tedious fine-tuning, but the evidence suggests that it is changes of this sort that produce real improvements, rather than grandiose plans for completely replacing our welfare arrangements. •