I foresaw the death of Harold Holt. It was three years before he drowned and it was the result of a chance encounter on the cliff above the beach where his life was to end. I keep returning to my recollections of that day, scrutinising them for significance. It was the summer of 1964–65; Mr Holt was fifty-six years old and I was seven. Can my childhood memory, however trifling, offer any clues to what happened on the day of his death, Sunday 17 December 1967, fifty years ago?

Since his disappearance in the surf — his body never to be recovered — theories and mysteries have abounded. Why did Holt casually enter such turbulent water? Was he showing off to his mistress, who was watching from the beach? Could the prime minister have been the victim of an assassination plot? Was it an act of suicide by a depressed man? Was he a spy who had a secret assignation with a Chinese submarine offshore? Had political treachery forced him to desperation or listlessness?

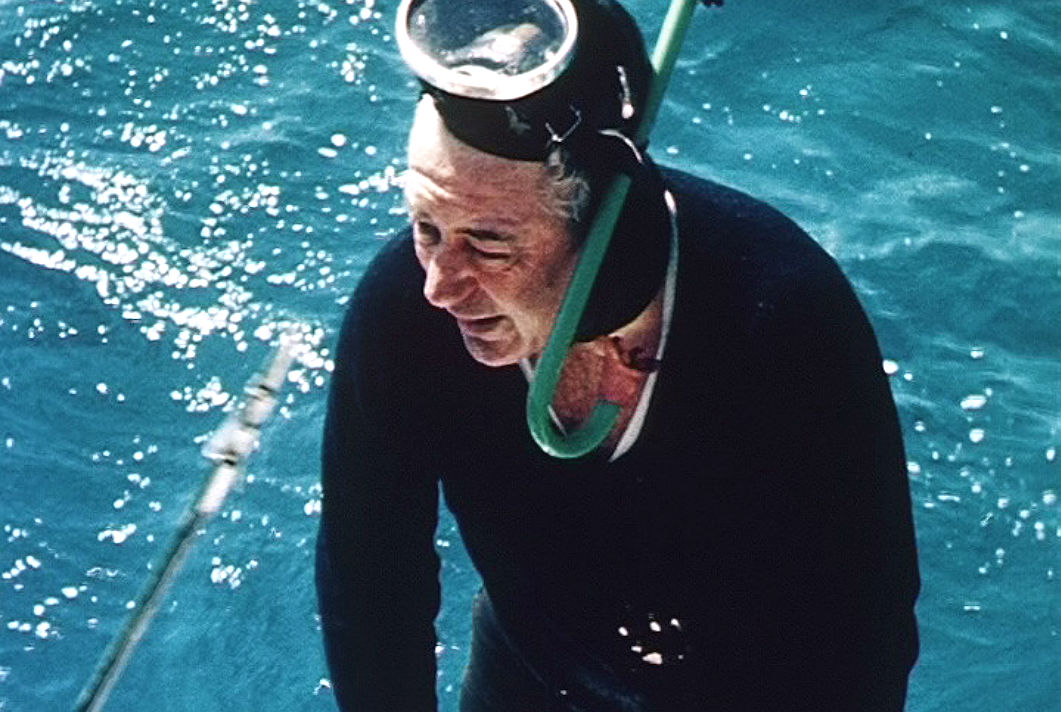

Harold Holt is remembered more for his death than for his life. But he had a long and distinguished parliamentary career that culminated in January 1966 when he took over the prime ministership. He had been Robert Menzies’s treasurer and became his anointed successor after sixteen years of conservative rule. Although he was only fourteen years younger than Menzies, he seemed to represent a new generation of leadership. He helped turn Australia diplomatically towards Asia, began to dismantle the White Australia policy and oversaw the successful 1967 referendum that removed discrimination against Aboriginal people from the Australian Constitution. He was a gregarious man who also enjoyed solitude, and he seemed to embody the swinging sixties. He relished spearfishing in the open ocean and was photographed in his wetsuit and snorkel at the surf beach with his bikini-clad daughters-in-law.

Holt and his wife Zara had a holiday house at Portsea near The Rip at the mouth of Port Phillip Bay. The Rip is the tumultuous stretch of water where two domains meet: the mass of water that comes in and out of the bay as a tide, and the heave and swell of ocean that has come all the way up from the Antarctic. The writer Barry Hill, who lives on the other side of The Rip from Portsea, in Queenscliff, has observed that “the two seas in the act of meeting and exchange create a turbulence as dangerous as anywhere in the world.” It is possible, he says, to see the bay’s water flow upwards as it exerts its will to escape over the southern swell. The turning of the tide in such a place is a moment of danger. It was here — just outside the bay and within the governance of The Rip — that Holt loved to go spearfishing, often alone.

Every Christmas, my parents would take my brother and me for a two-week holiday at Sorrento, where we would hire the basement flat of a house with a vast garden. A regular highlight of the holiday was a trip to Point Nepean, which has since become a national park but was then the site of an operating quarantine station and thus closed to the public. But my father was a Commonwealth public servant at the Government Aircraft Factory and applied each year for a quarantine pass, which we would solemnly present to the soldiers at the gate.

Once that gate was opened, we drove into a magic, mysterious world that was all ours to explore: the limestone buildings of the historic station, lonely beaches and sandy staircases, military bunkers and underground tunnels, catacombs and gun emplacements, and the fort that boasted the first shot fired in the British Empire in the first world war, a shell directed across the bows of a German ship attempting to leave the bay. My brother and I played freely in this sand-and-stone labyrinth, and never saw another soul. Later and rather unnervingly, when the national park was established, signs appeared beside walking paths, declaring: “Beware! Unexploded ordnance. Keep to the path!” Sometimes we would stand, windblown, at the end of Point Nepean, looking out across the tumultuous Rip where we could discern the bones of a sailing ship that had once foundered there, still visible in the jaws of the bay. Appropriately, it was the wreck of the Time.

One day, late in 1964, we presented our quarantine pass at the gate and proceeded into our remote, elemental playground, but this time we were surprised to find another car parked above Cheviot Beach. There was a man sitting alone in the front seat, waiting. When he heard our car, he appeared to wriggle back into his wetsuit and then got out to greet us. My parents exclaimed, “Good God, it’s the treasurer!” I didn’t know what a treasurer was but I suspected it was someone precious. Harold Holt looked cold, damp and famished. He explained that he had locked his keys in the boot of his car and asked if we could give him a lift back to his Portsea home, where he had a spare set. He had gone swimming in the early morning and appeared to have been waiting some hours. It was now early afternoon.

Mum hopped into the back seat with her boys, and our wet skindiver slipped into the front seat beside Dad. We drove the four or five kilometres back to Portsea while I discreetly scrutinised this “treasurer” who wasn’t very good with his keys. On arrival at his home, Holt disappeared inside while we waited in the car. Some time later he reappeared, dressed and devouring a huge sandwich, his first food since dawn. Zara was there, and a son, but Holt did not appear to have been missed. His long absence, skindiving alone at one of Victoria’s most dangerous beaches, had not apparently caused undue concern. He told us that his son would now drive him back to the car and invited us inside his home. My parents, reluctant to impose, declined. We left Mr Holt, eating ravenously and juggling a huge bunch of keys, wondering which of them would let him back into his car.

On the drive back through the quarantine gates and out along the headland, I remember my parents talking animatedly. They had just read The Rulers (1964), an analysis by journalist Don Whitington of Menzies’s long conservative reign, in which Holt, “the logical successor,” was pictured in skindiving gear holding a fish for the camera, with the caption: “Holt — fishing in deep waters.” That image had just materialised in our car, still dripping. Mum and Dad were incredulous that anyone, let alone the treasurer of the Commonwealth, would dive alone on such a perilous stretch of coastline.

My father was a keen body surfer and had introduced us boys to the ocean as soon as we could potter about in the froth. The relentless roar of the surf is one of my earliest memories. Dad would watch us carefully, keeping an eye on the weather and the tide, and taught us how to read a beach and look for currents. On this occasion, as we drove back out to Point Nepean, he spoke passionately of the renowned dangers of Cheviot Beach. He stood with us on the cliff and pointed out the rocks that shaped the three gutters that sucked water off the beach into the turbulent, heaving holes of bull kelp that lay just offshore. He feared for Holt. Thus I learned that there were rips as well as The Rip.

Three years later, when our television program was interrupted by a news flash from that very beach, we shared the shock of the nation but also felt somehow implicated. Shocked but unsurprised. The prime minister was missing. I felt that my father had predicted it.

The police report into the disappearance of the prime minister was completed within three weeks, while there was still some hope that a body or remains might be recovered. The inquiry determined that it was an accidental death by drowning. The report dwelt on the “ordinary domestic pattern” that witnesses disclosed and the good spirits of the prime minister in his final days. There were statements from fishermen about the currents and from Holt’s doctors about his health. It was appallingly simple: the man had misjudged his favourite medium.

But in the decades since, alternative theories have proven irresistible. By the end of 1967, Holt was under increasing pressure from Vietnam war protests and political scandals; on the morning of his death, he had a mysterious phone conversation with his treacherous treasurer, Billy McMahon; after his disappearance, police officers secretly removed papers from his briefcase at Portsea; Mrs Marjorie Gillespie, the Portsea neighbour and “family friend” who had accompanied Holt to Cheviot Beach, was also his lover. Serious, sinister and salacious as these facts might seem, none of them has revealed motives for Holt’s death or suicide. Holt had a record majority in parliament; McMahon was renowned for his scheming (and his use of the phone); the papers were removed from Holt’s briefcase at the behest of the governor-general, Richard Casey, who had written confidentially to Holt about McMahon; and Mrs Holt later claimed that Harold had many mistresses over a long period.

The most sensational conspiracy theory, set out in a book called The Prime Minister Was a Spy (1983), is that Holt worked for the Chinese government and was evacuated in a submarine before his identity could be revealed. But the chief source of the allegation, Ronald Titcombe, has been described as a “professional con man,” and the author of the book, British novelist Anthony Grey, believed that all life forms on earth were genetically engineered by an advanced extraterrestrial civilisation. The spy theory was coolly dismissed as a complete fabrication by Tom Frame in his fine biography, The Life and Death of Harold Holt (2005).

So let us return to the salty reality of the sea, to the cold, famished treasurer who could be absent half a day without raising his family’s concern, to the prime minister who loved the solitude, beauty and risk of the ocean and whose chief relaxation and touchstone of reality was the underwater world. Let us pay attention to the elements rather than to political intrigue or spurious informants.

Harold Holt did love the sea, as his gravestone declares, and as the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre bizarrely honours. His colleague Paul Hasluck, not a fan, actually wrote (without intended irony) that Holt’s greatest asset was his “buoyancy.” But Holt almost drowned twice in the year before his death, the worst occasion at Cheviot Beach when he turned purple and was rescued by companions. He constantly tried to build the strength of his lungs: Zara would sometimes come into the bathroom and find him face down in the water. Long, boring parliamentary debates offered him a chance to practise holding his breath.

Holt was not a swimmer so much as a diver. It was the watery depths that he loved, and they were opened up to him by snorkel, wetsuit and flippers. His friends considered him just an average surface swimmer; if he wasn’t equipped to dive he would generally just have a short dip to cool off. When Zara was told the awful news that he was missing, she asked, “Do you know if he was wearing his sandshoes or his flippers?” On being told that it was probably his sandshoes (as indeed it was), she replied, “Oh, he’s gone!”

When Sunday 17 December 1967 dawned, Holt rose early, walked into the kitchen, looked out the window and remarked to his housekeeper that the weather was puzzling. Local fishermen later testified that “the weather conditions were very bad” and that there were “very rough seas and surf.” Westerly winds were blowing with gusts of fifty to sixty kilometres per hour and there was “a strong flood tide travelling through the heads due to the high westerly winds.” There would have been a strong rip in Cheviot Bay due to the conditions. The nearby Portsea Ocean Beach, normally busy on a Sunday in summer, was closed for the day.

Holt, together with Marjorie Gillespie, her daughter Vyner and friend Martin Simpson, and another guest of the Gillespie family, Alan Stewart, drove in two cars to the old fort at the end of the peninsula to watch the British yachtsman, Alec Rose, come through the Heads. Rose was single-handedly circumnavigating the world in Lively Lady and felt the strength of the currents against his hull that day. After a few minutes viewing the distant yacht and the huge waves rolling in along the coast, Holt’s party decided to have a dip before lunch and drove back to Cheviot Beach. The day was hot and sultry and Holt was concerned about the weather. As they made their way down onto the beach, they observed that the tide was unusually high, and as they picked their way along the narrow remnant of sand, their legs were battered by heavy driftwood in the surf, mainly planks used on ships to secure cargo. There was so much timber in the water that a navy search-and-rescue vessel was later damaged by the buffeting beams.

High water that day was at 11.32am, and it was now approaching noon. The tide was turning. Mrs Gillespie and Alan Stewart said that the sea was higher than they had ever seen it at that beach. Martin Simpson waded cautiously in and retreated after feeling a strong undercurrent. Stewart also went in knee-deep but felt a “tremendous undertow.” Holt reassured them: “I know this beach like the back of my hand.” Having changed into his swimming trunks behind a rock, but still wearing his sandshoes, Holt walked into the water and, without hesitation, plunged in. The observers on the beach thought that he was swimming calmly and steadily away from the shore. But what they saw was a man who could not find a foothold in the unexpectedly deep water and was being swept out by a rip. As his skindiving companion Jonathan Edgar testified, “He would have been intending to swim out about ten to fifteen yards, stand up, brush his hair, and just swim back into the beach.” He had wanted a quick dip after the hot walk down the sand dunes. Holt’s political colleagues considered him impetuous, and he was often reluctant to admit when he was in trouble.

Holt had a recurring shoulder ailment about which he had recently seen two doctors. Sometimes he needed drugs to control the pain. Doctors had advised him to rest his shoulder, but he had nevertheless played tennis the preceding afternoon — although his movement had been a bit restricted and he was below his usual form. Marjorie Gillespie, his lover, told police that the shoulder disability meant that he “could not do an overarm stroke when swimming.” From the beach she watched him drift steadily away from her “like a leaf being taken out.” She could see his head above the water but rarely an arm. Across the breakwater she saw him enter a roiling turbulence and suddenly he was gone.

It is the habit of humans, especially political commentators, to underestimate nature. If my childhood memory has anything to offer, it is to remind us of the awesome power of the sea and the ordinariness and predictability of this Australian beach tragedy. ●