Towards the end of ABC TV’s special “Sovereign Borders“ edition of Q&A came an intriguing but frustrating back-and-forth about the number of migrants Australia welcomes each year.

The key protagonists were Shen Narayanasamy, GetUp!’s human rights campaign director, and retired general Jim Molan, co-author of the Coalition’s refugee and asylum policy and Tony Abbott’s former special envoy for Operation Sovereign Borders.

As the transcript reveals, the two speakers offered up very different numbers for Australia’s annual migration intake:

SHEN NARAYANASAMY: I think there is an alternative [to Operation Sovereign Borders] because when you understand that we take 800,000 people a year and we have done so since prime minister John Howard, the highest intake in history, it’s because we know it turbo-charges our economy and contributes to our society.

JIM MOLAN: 800,000 per year?

SHEN NARAYANASAMY: 800,000 per year.

JIM MOLAN: 200,000 per year.

SHEN NARAYANASAMY: No, 800,000.

JIM MOLAN: 200,000 per year.

SHEN NARAYANASAMY: This is the problem.

JIM MOLAN: 200,000 per year.

At this point, UNSW law professor and refugee expert Jane McAdam intervened in an attempt to clarify matters. She suggested that the two figures could be reconciled: Molan was referring to Australia’s annual intake of 200,000 permanent migrants, while Narayanasamy was including an additional 600,000 temporary migrants.

Neither of the two protagonists threw much light on the issue; in fact, the exchange probably only added to the level of public confusion, despite McAdam’s attempt to reconcile the figures. This was surely not the panellists’ intention. But combative, live television is not the best place to discuss statistics, particularly when they are complex. Counting the number of migrants Australia takes in each year might appear simple, but it is not really so straightforward.

All three panellists were correct in their own terms: Australia’s annual permanent migration intake is capped at just below 200,000 people (Molan’s figure) and each year around 600,000 migrants are granted temporary visas as international students, working holiday makers or temporary skilled workers (McAdam’s figure). Adding these two numbers together gives the total of 800,000 (Narayanasamy’s figure). But there are two serious problems in counting migration numbers in this way.

The first is that there is a big difference between the number of visas granted in any one year and the number of migrants who actually arrive. Many people granted visas are already in Australia, renewing an existing visa or shifting between different visa classes. Each time this occurs, no additional person enters Australia. They may be changing their status – which can have significant implications – but this doesn’t change the number of people who are coming and going across the frontier.

We know, for example, that almost half of Australia’s permanent migration program consists of people who are already here, generally on some kind of temporary visa. In 2015–16, 190,000 permanent skilled and family visas were granted, of which more than 91,000 went to people already in Australia. To include these people in the number of migrants Australia “takes” in a financial year is to engage in double counting.

The same issue arises in relation to temporary migrants. At least 100,000 of the people granted temporary visas in 2015–16 were transferring from one type of temporary visa to another: 36,000 working holiday makers obtained a second twelve-month working holiday visa; and about 73,000 international students moved to a different type of study visa (from an English-language course to university entry, for example), or to a 485 post-study work visa, a 457 temporary skilled work visa or a working holiday maker visa. There are also other movements across and within visa classes (when working holiday makers become students, for instance, or 457 visa holders renew their work visas). Again, since all these migrants are already present in Australia they can’t be included in the national annual “intake” without double counting.

If we exclude these two groups, then the number of visas issued to permanent and temporary migrants arriving in Australia from another country in any one year would fall below 600,000.

There is an added complication: the need to account for New Zealanders on “special category visas.” Under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, New Zealanders can enter Australia freely, to live and work for an indefinite period, and aren’t included in the migration program statistics. We can set the New Zealand issue aside, however, because it is part of the second, more significant issue we face in counting Australia’s annual net migrant intake – the fact that hundreds of thousands of people also leave Australia every year.

Many students, working holiday makers, international students and 457 visa holders go home at the end of their travels, their studies or their employment contracts. Some permanent residents and citizens also live outside Australia for extended periods, returning to previous countries of residence, pursuing job opportunities or following their hearts or their study goals.

So any meaningful attempt to quantify Australia’s annual migrant “intake” must also reckon with the number who depart – at least as long as our intention is to get a handle on the nation’s capacity to manage the impact of migration flows on such things as the demand for housing, jobs, transport, healthcare and government services.

After years of trying different measurements, the Australian Bureau of Statistics has settled on a methodology for counting migrants that takes account of both arrivals and departures while excluding short-term visitors like tourists. If you’re in Australia for twelve out of sixteen months, you’re included; if you aren’t, you’re not. This enables the ABS to come up with a figure for net overseas migration, or NOM, which is critical to understanding why Australia can’t be said to be taking 800,000 people a year.

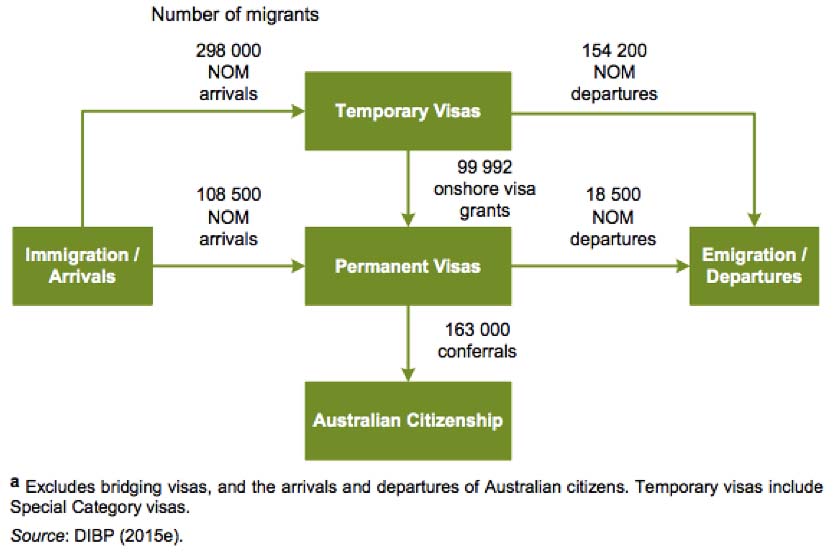

The big difference between the number of visas granted in any one year and the number of people who are in Australia for at least twelve months in a sixteen-month period, was neatly visualised in the Productivity Commission’s recent report, Migrant Intake into Australia:

Migration flows, 2013–14

Source: Productivity Commission, Migrant Intake into Australia, figure 12.3, page 416

The commission’s chart shows the many different migration pathways, including arrival on a temporary or permanent visa, the granting of onshore visas to people already here, departure or progression to citizenship. These are key to understanding why the number of visa grants doesn’t tell us how many people are arriving. The chart shows, for example, that 298,000 migrants came to Australia on temporary visas in 2013–14, yet in that year there were almost twice as many temporary visas issued (292,060 international student visas, 98,570 skilled worker visas, and 183,428 working holiday visas).

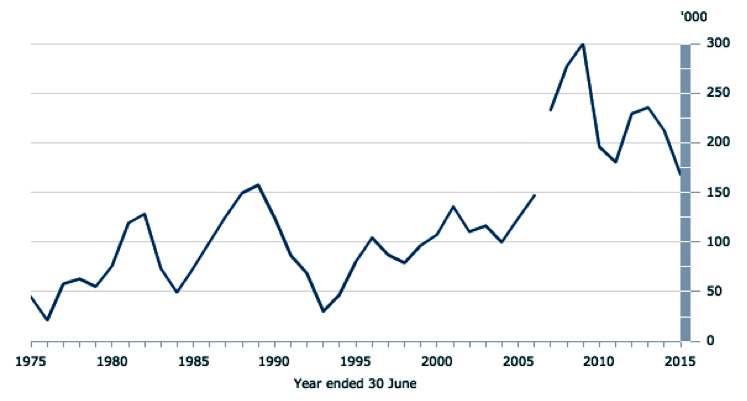

So exactly how many migrants does Australia take each year in net terms – that is, if we deduct departures from arrivals and exclude short-term visitors like tourists? In 2014–15, the ABS estimated the total was 168,200. As the chart below shows, the trend over the last six years has been for the net number of migrants to decrease.

Net overseas migration to Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Migration, Australia, 2014–15, 3412.0

There is a big difference between Net Overseas Migration of 168,200 people and the assertion that “we take 800,000 people a year.” Molan’s figure was certainly closer than Narayanasamy’s, but seemed to be based purely on the government’s annual quota for permanent arrivals, with no allowance for temporary migrants or departures.

GetUp!’s Shen Narayanasamy used her 800,000 figure to mount an argument in favour of increasing Australia’s annual humanitarian intake, including urgently resettling around 1500 people who have been recognised as refugees on Manus (561) and Nauru (929) but who continue to languish in those places at the government’s pleasure.

She laid out her case in much greater detail at the Wheeler Centre’s Di Gribble Argument in Melbourne the previous week. Identifying what she called “the great immigration con” perpetrated under prime minister John Howard, she argued that the overall size of our migration intake means we shouldn’t be anxious about boat arrivals and could certainly do much more to accommodate refugees. “At their panic-inducing peak in 2013, boat arrivals brought 25,173 people seeking safety to Australia,” she said. “Over the same period we welcomed 818,863 people on a variety of long-stay temporary and permanent visas… without anyone batting an eyelid. That’s an average of 2200 migrants coming through arrival terminals in our airports every single day.”

If 800,000 new migrants were arriving each year without being offset by a large number of people also leaving, then we would definitely notice dramatic differences in everyday terms. It would put significant strain on schools, hospitals, roads, public transport, housing and other services and infrastructure.

This is not to disagree with the politics of Narayanasamy’s position: as a rich, developed nation Australia clearly has the capacity to resettle many more refugees, including those on Manus and Nauru. The government’s claim that people smugglers would set sail again the moment Australia weakened its resolve on resettlement lacks merit. It is even less credible to suggest that taking up New Zealand’s offer to resettle 150 refugees each year from Manus and Nauru would reignite maritime smuggling. On Q&A, Molan suggested that the government had spurned New Zealand’s refugee resettlement offer because “in three years’ time, after they go to New Zealand, they have the right to come to Australia.” Aside from Molan’s factual error (it takes at least five years’ residence to become an NZ citizen), his claim that resettling refugees from Manus and Nauru is handing a “people smuggler somewhere in Java something to sell” isn’t convincing.

As Frank Brennan, Robert Manne, Tim Costello and John Menadue have argued, while Australian naval forces keep intercepting maritime asylum seekers and returning them to Indonesia (or Sri Lanka) the people smugglers will struggle to find customers for their trade:.

How many asylum seekers would be willing to pay people smugglers thousands of dollars when the overwhelming likelihood is disruption by Indonesian authorities or interception by the Australian navy and return to the place of their departure?

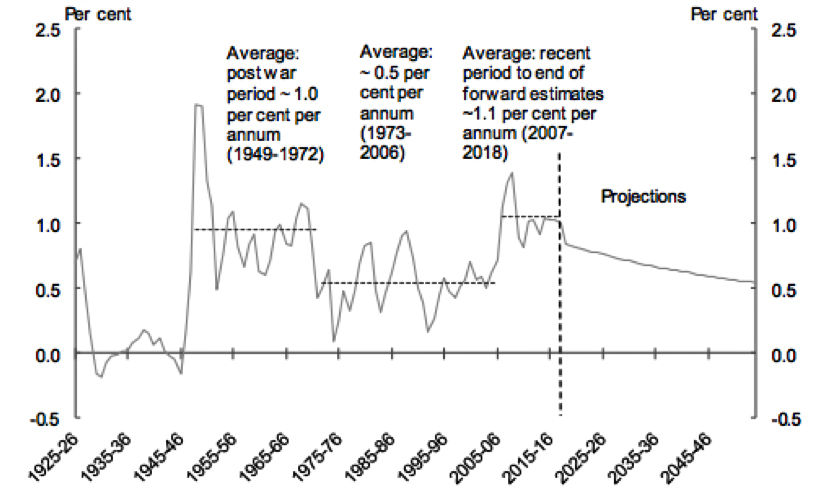

How, then, should we assess Australia’s capacity to resettle more refugees and provide them with housing, jobs, education and healthcare, without massive disruption to, or opposition from, existing residents? Rather than looking at absolute numbers, the best approach may be to consider Australia’s net migrant intake as a proportion of population. Making this comparison over time provides a more useful measure of Australia’s capacity to manage higher migration levels, including an increase in the resettlement of people displaced from war-torn countries like Syria and Iraq. A chart from Treasury’s 2015 Intergenerational Report provides this data:

Net overseas migration as a percentage of the population

Source: Treasury, 2015 Intergenerational Report: Australia in 2055, chart 1.5.

Looked at this way, it is clear that migration as a proportion of population peaked at around 2 per cent in the “populate or perish” years after the second world war, when Australia resettled tens of thousands of displaced Europeans. Migration fell to its lowest point under Gough Whitlam, then waxed and waned in the Hawke–Keating years before peaking again at around 1.5 per cent of population, under John Howard, in the first decade of the century.

What this chart doesn’t reveal are the dramatic changes to the migration system during that period, and particularly from the mid 1990s onwards. Until about the end of the cold war, the federal government generally maintained firm control over the number of people who entered the country. Each year, the permanent migration program was established in the budget with an allocation of permanent visas. These were virtually the only visas available, and their numbers were set by Treasury boffins based on their projections of future economic circumstances. As emigration from Australia also tended to be permanent rather than fleeting, this ensured the total number of people coming and going was pretty easy to count.

Today, governments and bureaucrats face a very different proposition. While the Australian government continues to set the number of permanent visas in the budget each year, migration overall is managed rather than controlled. There is no cap on temporary migration: the number of people who arrive as New Zealand citizens, international students, working holiday makers or skilled workers on 457 visas is determined by factors that are largely beyond government control: employers’ demand for overseas workers, the success of our universities and training organisations in attracting fee-paying international students, the exchange rate, and rates of youth unemployment in countries that are reciprocal partners in the working holiday maker scheme.

In this sense, Narayanasamy was right to claim in her Di Gribble Argument that John Howard doubled Australia’s migration intake while asserting that “we will decide who comes to this country, and the circumstances in which they come.” She was right, too, in saying that the disconnect between tight border control and high migration went virtually unnoticed in public debate, as did the transformation of Australia’s migration system from a tightly controlled program of permanent settlement to an uncapped and demand-driven scheme with high levels of temporariness.

Yet her laudable aim of encouraging Australians to support a much higher intake of humanitarian migrants needs to be based on firmer foundations than the flawed assertion that Australia already accepts 800,000 migrants every year (not least because for many people this high figure might be reason to slam the entry gate shut rather than open it wider).

Nor can humanitarian migrants – refugees and other displaced people – be compared easily with international students, working holiday makers or skilled workers on temporary visas, since they generally have very different characteristics. Humanitarian migrants are generally likely to be much less fluent in English and, on average, to have lower skills and qualifications. Statistically speaking, they will find it much harder to find employment and may come with a burden of trauma and illness. For this reason, humanitarian migrants need much greater levels of support than other migrants (whether temporary or permanent). Fiscal questions are also involved, since humanitarian migrants are immediately (and rightly) eligible for government benefits like Newstart and services like Medicare, whereas temporary migrants and new permanent residents are not.

None of this means that we should dodge the challenge of increasing Australia’s refugee intake, or support the government’s claim that Australia is already doing enough, or disagree with the proposition that large-scale humanitarian migration could be in Australia’s long-term interest (just look at how this country has benefited from the resettlement of displaced people from postwar Europe and of refugees from Indochina).

There is no doubt we could do much more. History, and migration numbers, tell us as much. In 1980–81 under Coalition prime minister Malcolm Fraser, Australia had a population of just below fifteen million people and resettled 22,545 humanitarian migrants. We have never reached that number again. If we resettled an equivalent number of refugees proportionally to our population today, then our current annual humanitarian intake would exceed 33,000 people. This is 75 per cent above the increased intake of 19,000 people promised by Malcolm Turnbull at the recent refugee summit in New York, and significantly beyond Labor’s election promise to increase Australia’s humanitarian intake to 27,000 by 2025. Yet we are a much richer country today than we were in 1981. •