Settling the Office: The Australian Prime Ministership from Federation to Reconstruction

By Paul Strangio, Paul ’t Hart and James Walter | The Miegunyah Press | $49.99

A visitor to Australia, knowing nothing of the country’s history or institutions, might consult the constitution to understand how the place functions. There, the visitor would find the powerful figure of the governor-general, yet reading the newspapers, watching the news and listening to people talk would yield barely a mention of this personage. Instead, the focus is on someone called the prime minister, of whom not a single mention can be found in the official rule book. How can this be so?

The answer is both simple and complex. The simple answer is that the office did not exist at the time the constitution was framed and given legislative effect by an Act of the British Parliament, whereas the Crown, whose representative the governor-general is, was already extant and clearly defined. The complex answer is that both the office and the function of the prime minister were created as part of the machinery of government necessary to add administrative muscle and flesh to the constitutional skeleton; neither was defined, but each has evolved over time.

A timely study by three scholars, charting this evolutionary process over the first half-century of the Commonwealth, sheds much light on the clearing of the path, not always linear, that would vest national leadership, symbolic as well as real, in an office to which the founding fathers gave little or no thought. We see how individuals holding the office have added to that office incrementally, sometimes through trial and error, occasionally by design.

Settling the Office identifies two very different types of leader – the personalisers (Billy Hughes, Kevin Rudd) who see everything through the lens of their own inclinations (to which the recently departed Tony Abbott must surely be added) and the process-oriented (Stanley Bruce, Malcolm Fraser).

But when we look at the historical record, we find that in just 115 years of the Commonwealth, Australia has had thirty-five prime ministerships, averaging just three years each, and twenty-nine prime ministers. Of course, when we factor in the eighteen years and five months of the two terms of Robert Menzies (1939–41, 1949–66), the eleven years and eight months of John Howard (1996–2007), the eight years and nine months of Bob Hawke (1983–91) and the seven years and four months of Malcolm Fraser (1975–83), just to mention the four longest-serving, we see not only that some have had far more opportunity to shape the office than others, but also that some barely warmed the seat.

The authors describe the early years as the period in which the office was invented. The title of prime minister, though, was far from unfamiliar. In fact, colonial Australia was awash with prime ministers: the heads of the colonial (pre-Federation) governments in New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania had generally accorded themselves the title of prime minister (the other colonies opting for “premier”). As late as 1908, William Kidston, the Queensland premier, was styling himself “prime minister of Queensland.”

Indeed, at the various Federal Conventions during the 1890s that thrashed out a basis for federation of the colonies and eventually drafted the constitution, all the attending heads of government alike, whatever they styled themselves, were assigned the title of prime minister. While some discussion ensued about the title itself, the proceedings were marked by almost total silence in regard to the powers and functions of a prime minister in a federated Australia.

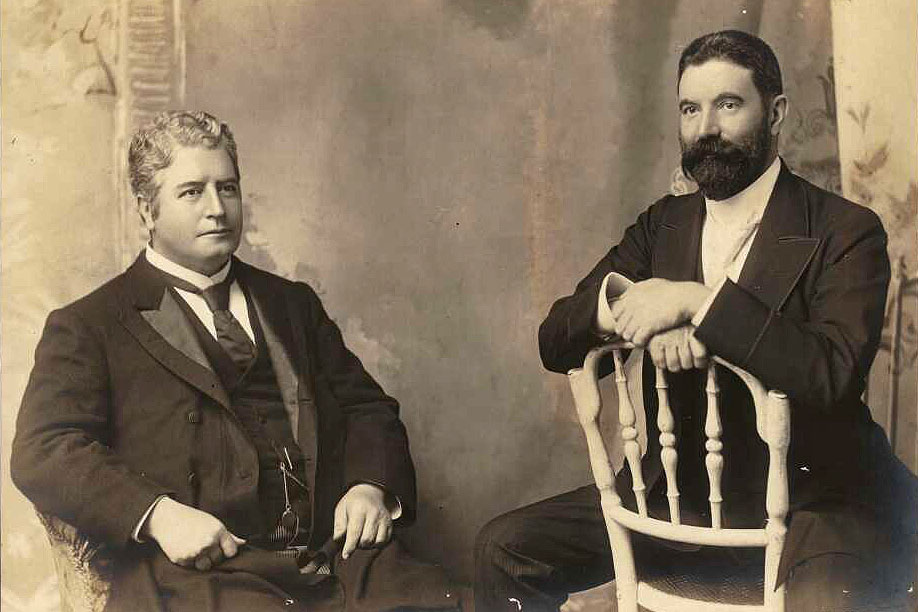

Right up to the end of 1900, just weeks before the Commonwealth came into existence, it still had not been decided what to call the head of government. Edmund Barton, soon to be the first holder of the office, expressed doubts as to the “constitutional propriety” of presuming titular equivalence with the leader of the British government at Westminster. It took Alfred Deakin, who would be the second holder of the office, to convince Barton that it was a title steeped in history and would usefully distinguish the office from that of state premiers. So, prime minister it was.

Assuming office at the start of 1901, pending elections in March, Barton was very much, at the start, prime minister in name only: his role undefined, his authority unclear, his powers unknown. He didn’t even have a physical office (later remarking that at the time he had carried the “whole federal archives in his Gladstone bag”). His entire staff consisted of one person, a private secretary, Attlee Hunt, who wrote in his memoirs, “No clerical staff had been detached temporarily to assist ministers; there was not even a messenger; no stationery had been ordered, no place set apart where officials might work.”

It fell to the home affairs minister, William Lyne, to organise for Barton an office in Sydney, where he lived. But Lyne had been passed over for the prime ministership and, according to Hunt, he was “not disposed… to smooth the path” of Barton. Lyne (who was concurrently prime minister of New South Wales) arranged an office on a balcony of the overcrowded NSW Treasury building in Macquarie Street that was also used as a thoroughfare and exposed to the weather.

Nonetheless, the machinery of government, albeit rudimentary, was slowly assembled, and Barton set about creating the office. After two years at the helm, Barton happily left for the High Court, to be succeeded by Deakin, who is credited as the driving force of the office’s early evolution. Deakin was very much constrained by the political situation, though: his first two administrations were minority governments relying on the support of Labor.

The slow development of political parties in colonial Australia had created a situation in which political leaders generally held office through personal loyalties rather than party position, and this spilled over into the early Commonwealth. But with the nascent Labor Party on the rise, the two non-Labor groupings – Deakin’s Protectionists and George Reid’s Free Traders – were forced to organise as quasi-parties to combat their common foe. Deakin’s complaint about three almost equal parties in the parliament being akin to a cricket match with three elevens on the field highlighted the inherent instability in that first decade of Federation.

Deakin, as the authors rightly observe, was the undisputed ringmaster of that first decade, making and breaking governments and prime ministers with them. It was Deakin, after losing Labor’s support, who had Labor’s Chris Watson installed and it was Deakin, four months later, who had Watson put out. Deakin arranged for George Reid to take over and a year later he had Reid removed.

Between the inception of the Commonwealth and Deakin’s electoral defeat in 1910, what we have is the beginning of the exercise of prime ministerial power, depending very much on Deakin’s own highly personalised leadership style. The dominance of parties was not yet apparent.

The coming to office of Andrew Fisher in 1910, at the head of the first majority government, heralded a shift. Given Labor’s ambitious social program, Fisher was aware of the need to maintain the confidence of the party. His nation-building project was impressive, as was his attention to the needs of a chief executive, establishing for the first time a prime minister’s department as an initial step in institutionalising the resources available to the head of government.

Billy Hughes was a driving force in all three Fisher governments, but his prime ministership on succeeding Fisher could not have been more different. Dynamic, mercurial and at times brilliant, Hughes left chaos trailing in his wake, splitting his party and defecting to the other side while retaining the prime ministership. With the war bringing unprecedented focus on the federal government, it was Hughes who made the office of prime minister not only highly visible but also resoundingly influential.

But all-powerful he was not. He became the first prime minister to fall victim to the party system when he was forced out in 1923 after the new Country Party insisted on his removal before it would join a coalition with the Nationalists.

Bruce, succeeding Hughes, was different in every way, not least because he was the first prime minister not to have been part of the federation process. Aghast at the way Hughes ran his government according to whim, Bruce became the first incumbent to take meaningful steps towards professionalising cabinet and its procedures. Coming from a business background, he insisted on a proper agenda for cabinet meetings, the circulation of ministerial briefs, and full discussion. It was Bruce who made cabinet a more deliberative body than had previously been the case.

Bruce was also an innovator in another sense. He was the first prime minister with what we would now call a narrative: his mantra of “men, money, markets,” focusing on the need for population and economic growth, was an important framing tool for his policies. He was also instrumental in highlighting the need to reform federal–state relations, even if he achieved little.

The hapless prime ministership of James Scullin (1929–32) served to highlight the limits of prime ministerial power and authority: he was opposed by hostile state governments, hostage to external forces such as the Commonwealth Bank, and undermined by a party at war with itself. An inability to control the party badly weakened Scullin.

His successor, Joseph Lyons (1932–39), an ex-Labor man, brought a semblance of assurance to a Depression-ravaged nation; he was the first media-savvy prime minister, using radio and press coverage that projected his relaxed persona. Though he was popular with the public, he faced tough problems at the cabinet table, his authority constantly under challenge (and even derided). For all his appeal, he was more a figurehead than a potentate.

Robert Menzies (1939–41) came and went in his first incarnation, another victim of party intriguing. It was the succeeding prime ministerships of John Curtin (1941–45) and Ben Chifley (1945–49) that would do most to shape the office.

Curtin was fortunate in having the loyal Chifley to manage the party, containing as it did formidable figures such as Bert Evatt, Arthur Calwell and Eddie Ward. Both men had learned from a past that demonstrated prime ministerial authority was dependent to a very large extent on authority within the party. They also used the wartime emergency to increase federal powers, especially over finance, and to draw on academic and industrial expertise to professionalise the public service and to broaden the advice and resources available to the government, and especially the prime minister. It was in this period that the modern prime ministership began to take shape.

The second volume in this erudite, fascinating and very accessible history is eagerly awaited. •