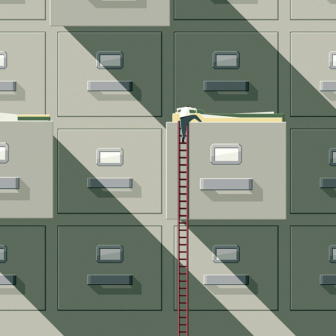

LEGAL scholar Savitri Taylor is frustrated. As one of Australia’s leading researchers on refugee issues, the associate professor of law at La Trobe University maintains a keen watch over Senate estimates hearings, which often provide important insights into the operation of Australia’s asylum seeker policies. This is particularly true of responses to questions on notice – questions that government officials can’t answer on the spot and undertake to respond to at a later date. Senate committees set deadlines – generally about seven weeks after the hearing – for the answers.

Taylor’s frustration stems from the fact that over the past year, with increasing boat arrivals and major policy shifts putting refugee policy in the spotlight, the Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s record on answering those questions has deteriorated. In fact, Immigration has consistently and repeatedly failed to answer many important questions in a timely manner, if at all.

Since October 2012, at three separate hearings of the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, departmental officers have taken a total of 1722 questions on notice. So far, the committee has only received answers to about half of them, though the deadline for responses has long expired.

Questions on notice are often pointed and specific, and they can elicit information about government policies and practices that is revealing in substance and detail. Some of Immigration’s unanswered questions go to the heart of contentious policies, including the reopening of detention centres in Papua New Guinea and Nauru. As Taylor puts it, “Far more questions have been asked about regional processing at Senate estimates than have been answered.”

In October 2012, for example, WA Liberal senator Michaelia Cash asked Immigration officers a series of questions about the transfer of asylum seekers to Nauru and Manus Island. How many flights had the department chartered to Nauru and Manus and at what cost? What airline has been contracted to move freight to Nauru and Manus and what is that contract worth? How did the department establish that it was getting value for money? Has the department had any discussions with the International Organization for Migration about the establishment of centres on Nauru and Manus? Was the IOM invited to tender for any aspect of the management of these centres? If not, why not?

These were some of the 647 questions taken on notice by Immigration at the supplementary budget hearings of the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee in October 2012. The committee set 7 December 2012 as the date by which responses were expected. Almost nine months after that deadline had passed, however, about one in five questions remained unanswered.

The department has exhibited similar tardiness in subsequent estimates hearings. At the additional estimates hearings in February 2013, 509 questions were put on notice with answers due on 30 March. At the time of writing, 176 of those questions – just over one in three – remain outstanding. Not one answer was provided before the due date, and more than 300 answers were received in one batch on Saturday 25 May, just two days before the 2013 budget estimates meeting of the committee. The volume of material made it difficult for senators to effectively process the answers and use them to inform the hearings.

The May estimates hearings resulted in another 568 questions being taken on notice by Immigration, with answers expected by the committee by 12 July. So far not one answer has been provided. At that hearing the secretary of the department, Martin Bowles, admitted that the department had “dropped the ball a little bit” in this regard. “In fairness,” he said, “the number of questions we get is escalating. Nothing we deal with is simple. Everything is complex. We try to get these things through the system, but Senate estimates is not the only list of questions we get. We get them from other Senate and joint committees and all sorts of other processes. The number we are getting is, unfortunately, escalating quite significantly. These people are doing their day jobs as well.”

The multicultural affairs minister, Kate Lundy, has offered a similar defence of the department in parliament. “Over the past seven hearings since the supplementary estimates hearings in October 2010 there has been a significant increase in the number of questions on notice,” she said. “They are doing their utmost to respond to those questions.”

Senator Cash is unimpressed. She points out that other departments seem better able to respond to questions from senators. She says, for example, that at the additional estimates hearings in February 2013 Treasury took 1180 questions on notice from the Economics Committee. Only thirty-nine answers remain outstanding. “In terms of where the Department of Immigration and Citizenship sit on the leader board of tardy responses to questions on notice,” says Cash, “they lead it, by a long shot.”

The senator says there are three possible reasons why the department had failed to provide answers: “They don’t know the answers, they’re too embarrassed to give the answers or they do not want the Australian public to know the truth about how far this portfolio has deteriorated under Labor’s watch.”

In defence of the department, it is true that it has been confronted with an avalanche of questions (particularly from the energetic Senator Cash). Some of the unanswered questions are detailed and could require staff to spend a significant amount of time searching through files or recalculating data. Other questions, however, appear almost ridiculously straightforward – for example, does the Nauruan public dental service have more than one dentist?

Some questions go to the heart of policy and potentially reveal major shortcomings and inconsistencies. How, for example, does the No Advantage principle work in practice? The idea of No Advantage is to remove the incentive to travel to Australia by boat by ensuring that it does not provide a faster route to resettlement than the processes on offer through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In October, Senator Cash asked how this would operate. Would No Advantage be applied differently for different cohorts of asylum seekers according to their circumstances? Would an Afghan asylum seeker who had made an application for refugee status in Pakistan, for example, be treated differently from an Afghan applying for refugee status in Malaysia or Indonesia? No responses have been provided.

Whatever workload pressures the department is under – and they are no doubt intense – it is hard to escape the conclusion that some questions are not being answered in a timely manner because they are politically inconvenient or because they would provide a level of openness and scrutiny that government would rather avoid.

In October 2012, for example, Greens senator Sarah Hanson-Young asked Immigration officers to provide a copy of the manual used by the private security company Serco to train its employees in how “to conduct themselves and run facilities in detention centres.” Almost a year later, this question remains unanswered. Presumably Serco has a training manual. If it does, then it is difficult to understand how it can take more than ten months for it to be presented to a parliamentary committee in response to a clearcut request. If no manual exists, then it should have been possible to answer the question even more promptly.

An exchange between Senator Cash and the secretary of the department, Martin Bowles, sheds some light on the process of answering estimates questions, and suggests that the hold-up may sometimes involve the minister’s office rather than the department. Bowles explained that when questions on notice are received they are farmed out to relevant line areas for a response. The responses come back to his office for clearance and are then sent to the minister’s office before being provided to the committee. Senator Cash pushed to know more:

Senator Cash: Do you track the date on which you send to the minister’s office the answers prepared by your department?Mr Bowles: We just started that process.

Senator Cash: On what date did you provide the answers to the October estimates to the minister’s office?

Mr Bowles: It will be various dates, and I am not quite sure how far I can go back and track it. I can take that on notice and try to see where we can come up with the —

Senator Cash: To be fair to the department I am trying to work out if the tardiness is with the department or with the minister? If you can say to me, “We provided the October ones in November,” then I do not have any argument with the department.

Mr Bowles: I am being very up-front with you. We have been tardy in the department. There are some that we just have not got to. There is a range of reasons. In the minister's office, between February and now, we have had a change in minister and change in the minister’s office staffing. That plays into it as well, from that perspective.

To press her point further, the senator drew the secretary’s attention to the fate of a particular question – question AE13/0183, posed in February 2013, which asked about the blowout in budgeted costs for asylum seeker management since November 2007. The answer, provided in May, was “See answers to AE13/0016 and AE13/0017.” As Cash noted with some amusement, however, questions AE13/0016 and AE13/0017 did not yet have answers themselves:

Senator Cash: I am sure we all know where this is going, because then when you flick through your bundle and you find that those answers have not been provided, I think the obvious question arises. Why? And that is not the only example. I just want to see where the fault lies, and obviously I would like to see the answer to that question, because it is of particular interest to me.Mr Bowles: Clearly they are in our system somewhere between us and the minister’s office. I would have to check specifically where they are.

Senator Cash: How does an answer get left —

Mr Bowles: Because they would all be done at a similar time, probably. This one has been released and the others have not at this point.

THE estimates process is one of the most important mechanisms of transparency and accountability in Australian democracy, because it allows senators to pose direct and specific questions to departmental officers who are obliged to provide truthful answers. The requirement to provide answers continues, even when parliament is prorogued for an election.

Unfortunately, though, when a department fails to answer questions, the remedies are limited and far from immediate. Senator Cash says the only action she can take is to raise the matter in the Senate chamber under standing order 74(5) and ask the responsible minister why questions have not been answered. (Clearly, this can only happen when the Senate is sitting.)

If the minister fails to provide an answer then the senator can seek to move a motion to debate the matter. As the deputy clerk of the Senate, Richard Pye explains, “This may be considered to be both an accountability mechanism and a procedural penalty, as it diverts scarce debating time from other matters, including from the government’s legislative program.”

If debate in the chamber still fails to elicit results, then a senator may move a motion to require the production of answers by a given deadline. Pye says that this “raises the profile of the matter from a committee concern to a concern of the Senate itself” and puts “further pressure on the government to provide answers.”

If the government still refuses or fails to respond then the Senate can use procedural penalties to escalate the matter one step further – “for instance,” says Pye, “in the Senate refusing to deal with related legislation until the matter is resolved.” The Senate resorted to this ultimate penalty in the first half of 2009, when the government failed to respond to an order to produce documents about the National Broadband Network, by postponing consideration of any government legislation relating to the project until the documents were finally provided.

If there is a change of government on 7 September it will be interesting to see how committed Senator Cash remains to pursuing responses to many unanswered questions. As Savitri Taylor from La Trobe University says, the failure to answer questions on notice goes far beyond political point-scoring or academic frustration. “The proper functioning of democracy depends on an informed citizenry,” she says. “If citizens cannot find out what their government is doing in their name, they are not in a position to hold government accountable for those actions at election time or any other time.” •

• The Department of Immigration and Citizenship was approached for comment during the writing of this article and undertook to respond to specific questions by the end of August. At the time of writing, no answers had been received.