After nearly ten months of political uncertainty, Saturday’s parliamentary elections in Timor-Leste delivered a decisive result. The Change for Progress Alliance, or AMP, a coalition of three parties led by Xanana Gusmão, won 49.6 per cent of the national vote, delivering thirty-four out of sixty-five seats and winning a narrow majority in its own right. In Timor’s proportional system, where outright majorities aren’t common, this was a strong vindication of the decision to combine the forces of Gusmão’s CNRT with Taur Matan Ruak’s Popular Liberation Party, or PLP, and the smaller youth-focused party KHUNTO in a formal pre-election coalition.

This was a polarising election. The AMP achieved a swing of 3.1 per cent on its collective 2017 results, though the entry of a new party saw its tally of seats fall by one. Fretilin received 34.2 per cent of the national vote, and twenty-three seats, maintaining its 2017 seat tally. This represented a substantial swing of 4.5 per cent, though it proved insufficient to overcome the formidable AMP coalition, as the swings to both major groupings came at the expense of smaller parties. The result sees Xanana Gusmão back as PM, at least in the initial phase of the new government, ousting the Fretilin–Democratic Party minority government led by Mari Alkatiri. The Democratic Party is also back in parliament with five seats (down from seven in 2017), and a new coalition, the FDD, has three. The AMP government is likely to form a ministry from within its own ranks, though the FDD may well be invited in later.

With many residents back in their home districts to vote, Dili was unusually quiet in the wake of a divisive and heated campaign. Though observers remain alert to the potential for trouble in coming weeks, there seems no immediate prospect of it occurring in the wake of the poll. The campaign and its divisive prelude in 2017 clearly drove the electorate towards the larger players, with 84 per cent voting for the two major blocs and over 97 per cent of the vote going to four parties. The entire electorate seemed to want to ensure their votes would count, and abandoned the parties unlikely to clear the 4 per cent hurdle to win seats. Turnout was a strong 81 per cent, up 5 per cent on last year.

Some results in the districts were significant. Repeating similar patterns since 2007, the AMP won the ten western districts. Of particular interest was the large swing against Fretilin in the district of Oecusse. It was here that Fretilin recorded its only fall in votes in any district. The fact that the party has had sole responsibility for the district’s Special Economic and Social Market Zone project in recent years will no doubt play on the minds of party strategists, and local Fretilin chief Arsenio Bano apologised publicly for the performance to his leader on Saturday night. In Dili and the eastern districts of Viqueque and Baucau, on the other hand, Fretilin performed strongly, gaining large swings.

With an AMP government and a Fretilin president, the next few years will demonstrate what “cohabitation” looks like in Timor-Leste’s semi-presidential system. Given that previous presidents have been independents, this will be a first, and is likely to test the constitutional relationship between president and parliament, and the scope for presidential vetoes of legislation. Some vetoes are reversible by a simple majority in parliament (though vetoes of decree laws issued by the government are irreversible), but reversing certain other vetoes requires a super-majority of two-thirds. These include legislation in such key areas as “the budget system,” which means the president has the power to veto future budget legislation or refer it to the courts to test its constitutionality — a power former presidents José Ramos-Horta and Taur Matan Ruak used at different times.

An important difference between Ruak’s veto of the 2015 budget and any potential veto during this parliament is that Ruak was exercising his powers in the era of the de facto national unity government, which meant the government could draw on a super-majority to reverse it. Fretilin’s twenty-three seats in the new parliament means that non-Fretilin forces are one short of the super-majority of forty-three seats.

The political stalemate of the past ten months, and the effective freeze on government spending have inevitably affected the economy. Given this, insiders believe the president is highly unlikely to veto the first budget, but could, like other presidents before him, do so in future, and with fewer prospects for reversal. This indicates the potential scope of “cohabitation”-related stand-offs over the next few years.

With a clear majority, the AMP will now set about forming a new government and passing a much-needed budget. The major question yet to be answered is how the coalition will reconcile the CNRT’s focus on megaproject-led spending with the PLP’s focus on basic development spending in health, education and agriculture. On the campaign trial, Gusmão acknowledged “mistakes” by his previous governments and gave the floor to the PLP and KHUNTO leaders to address these issues in rallies — a sign he was listening and open to change. Some AMP supporters see this as a second chance for the great resistance leader to consolidate his other legacy as a leader of government. Though his previous governments brought social stability, economic growth and much else, there is a sense that spending on basic development measures has lagged badly, and far too much has been spent on big infrastructure projects.

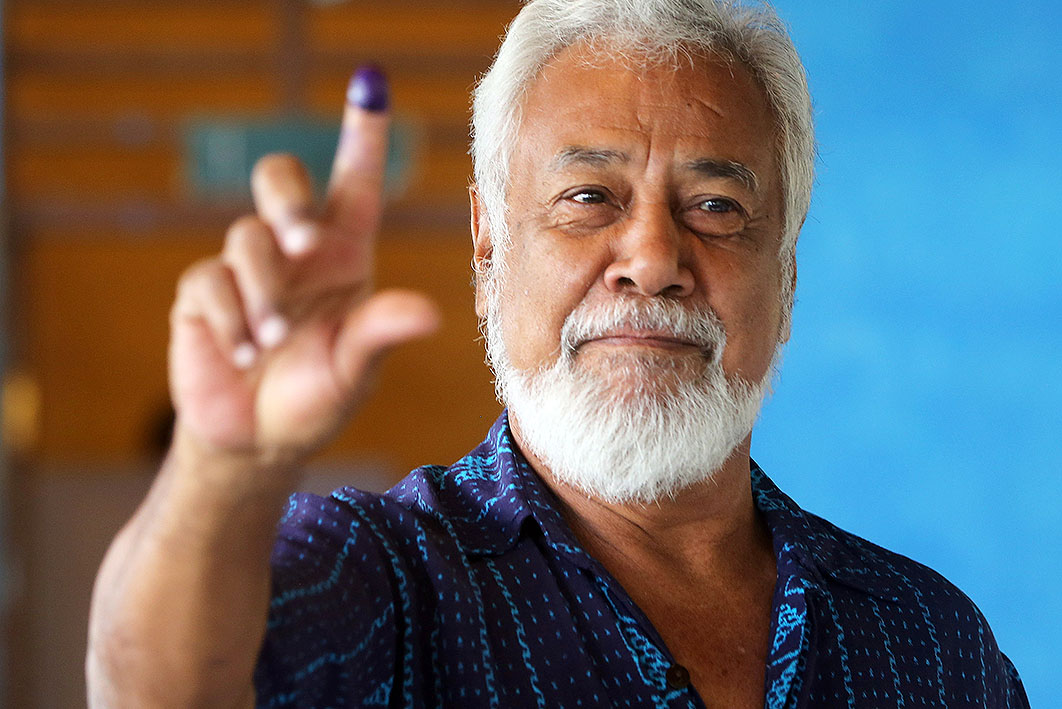

Election day passed without major incident, though comments from Gusmão on the day that he “would not accept the result if it was not fair” were unhelpful, and built on a series of complaints from AMP in the campaign that were not backed by strong evidence. In its preliminary report, the largest observer mission referred to the “injudicious and inappropriate language of some political representatives” and noted that allegations about the election process are “serious in character and, if made, need to be supported by evidence.” On Monday, Fretilin raised similar concerns over the vote in Oecusse, again without immediately offering compelling evidence. Timor-Leste’s two electoral agencies again did an excellent job despite the pressure of the re-run campaign and limited budgets.

Saturday’s win for the AMP was a clear and decisive one, and many in Timor will be relieved at the end of political uncertainty and protracted coalition negotiations. Though some in the AMP saw the election as a chance to put Fretilin away for good, and some projected a massive win, the Fretilin vote grew significantly for the first time since the post-crisis election of 2007, demonstrating the impact of new affiliations by independents and, perhaps, new support from elements of the church. Though Fretilin is deeply disappointed by the defeat, it has increased its support base in 2018 and is likely to remain the biggest single party in the country. The AMP may come to see Fretilin’s continuing strength as a reminder of the need for discipline and unity in its three-party coalition, and hence as a positive.

Great challenges lie ahead for the new government, including the need to diversify the economy before the sovereign wealth fund, based on finite oil and gas reserves, depletes somewhere in the late 2020s. In this process, it is clear it will face a strong opposition determined to hold it to account. •