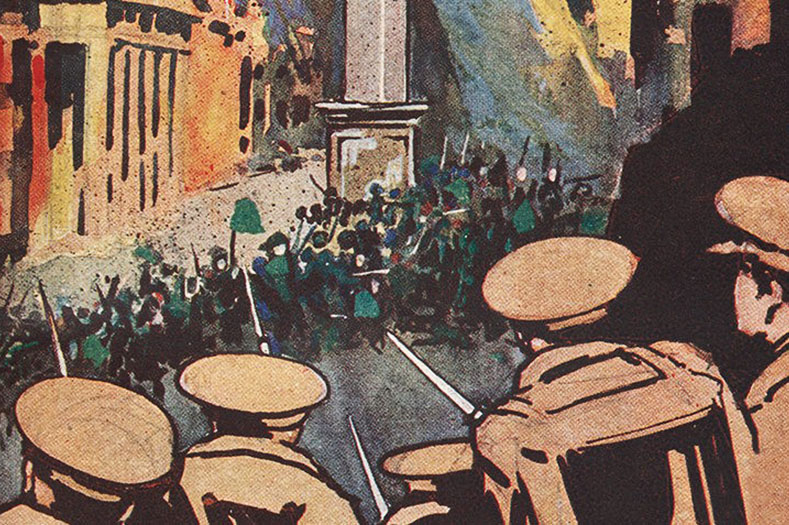

Eight choreographers, all women, create pieces around the theme “Dancing the Proclamation,” interpreting anew the document that launched the armed rebellion in Dublin a hundred years ago. A conference on multilingualism in Ireland cites the presence of a Finn and a Swede among the core group of insurgents, many of them Irish speakers, who seized the city’s General Post Office on 24 April. The city’s beloved Little Museum hosts Fergal McCarthy’s cartoon history of the “Easter Rising,” its sixty panels a witty synopsis of those six days and the subsequent execution of fifteen leaders, which transformed the sympathies of much of the population against the British.

The list of commemorative and spin-off events – running to forty-eight pages in the official program – extends far beyond Ireland itself, including to Australia and New Zealand, reflecting both the reach of the country’s diaspora and awakened interest in the international impact of “1916.” The State Library of Victoria, for example, is hosting an exhibition called The Irish Rising: “A Terrible Beauty is Born” in partnership with the University of Melbourne, where a conference exploring Australasian perspectives on the rising was held on 7–8 April.

A symposium on “Easter 1916 and Cultures of Anti-Imperialism” took place on 1 June at the University of New South Wales. And in Dublin itself, a lecture by Mark Finnane of Griffith University on “The Easter Rising in Australian History and Memory” last October traced the rebellion’s domestic impact, including officialdom’s use of “surveillance, internment and postwar sedition law” in the aftermath, which became “an enduring legacy, whose origins deserve our attention.”

Every big national anniversary is about now as much as then, a renegotiation between past and present on the latter’s terms. Ireland, for all its lived experience of coming to terms with unquiet history, had little practical guidance in how to bring this one off. Events subsequent to the rebellion, among them the independence war of 1919–21 and civil war of 1922–23, had confirmed 1916 as a landmark moment that came to make self-rule in some form inevitable. The “decade of centenaries” would soon have to face, and surmount, those conflicts. But just as the rising itself shifted Ireland’s political ground, so the manner of its observance would influence those to follow. This makes the 1916 agenda – whose overarching themes are “remember, reflect, reimagine” – all the more telling.

Ireland’s principal commemorations of 1916 have always aligned with the movable feast of Easter, which in 2016 arrived in late March, four weeks earlier than a century ago. The custom, and indeed the very term “Easter Rising,” recall the powerful fusion of religious and national motifs that came to be attached to the rebellion: sacrifice and redemption, insurrection and resurrection, martyrdom and transcendence, saintly icons and secular relics. This outcome also had profound effects in the years that followed, particularly on Ireland’s landscapes of the mind and thus its character. Even if these threads present a less tangible focus for public ritual, they too are an inescapable part of the 1916 retrospect.

Earlier in the centenary decade, there were signs of what the latest renegotiation between past and present might bring. One was the successful campaign to name a new Dublin bridge after Rosie Hackett, a worker prominent in the city’s great lockout of 1913, an insurgent in 1916, and a lifelong trade unionist. Hackett turned out to be one of many women whose exploits had been marginalised, neglected or forgotten. A great excavation followed, with already illustrious figures of the period – notably Constance Markievicz and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington – being joined in public and cultural retrieval by the Irish Citizen Army’s Kathleen Lynn, the actor-activist Helena Molony, the Scots-born maths teacher and combatant Margaret Skinnider, and a host of others previously unregarded. Along the way, the proclamation’s explicit address to Irish women and reference to their voting rights struck a fresh chord.

(Skinnider, the only woman shot during the fighting, applied for a pension in 1925 and was told that the “definition of ‘wound’” under the Army Pensions Act of 1923 “only contemplates the masculine gender.” It took thirteen more years for her to win that lone battle. Like the testimony of many veterans, Skinnider’s was recorded in the 1960s by the state broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann, or RTÉ.)

Another indicator of the negotiations between past and present has been the detailed attention paid to the experiences of “ordinary” people a hundred years ago: as participants in the rising, for example, but also as diarists and letter writers, affected bystanders and children. In the last case, much is made of the proclamation’s pledge to “[cherish] all the children of the nation equally.” The phrase was intended to reassure hostile northern unionists – those who wanted no change in the ties with Britain – as suggested by the next clause: “oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government.” Yet the contemporary reading has taken hold, bolstering the merited acclaim of Joe Duffy’s Children of the Rising, which tracks the story of each of the forty children who died.

Another sign is the way interest in the period is spreading across military and political divides, building on the more inclusive approach to public commemoration of Irish history since the 1990s. Stories of rival allegiances within the same family, for example, are increasingly common, as are accounts of Irish soldiers in the British army during the Great War (over 200,000 were to sign up). Ronan McGreevy, founder of the Irish Times’s brilliant centenary website and author of Wherever the Firing Line Extends: An Irish Journey Along the Western Front, notes that 532 Irish servicemen were killed by the Germans during the week of the rising alone, most from a chlorine gas attack around Hulluch in northern France, which consumed the 16th (Irish) Division. In the rising and its wake, 488 died on all sides.

One of the latter was Margaret Naylor, who was fatally shot in Dublin on 29 April when she went out to buy bread for her three children. The same day, her husband John, a private in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, was killed near Hulluch. In the thousands of individual episodes and testimonies now being accessed, uncovered (in some cases rediscovered), cross-referenced and explored, a larger record of Ireland’s centenary decade is in the making.

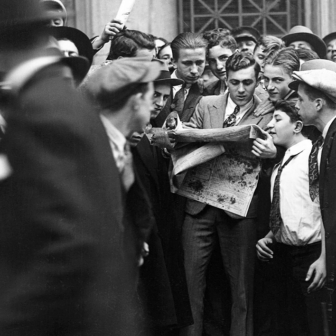

A confluence of four trends foreshadowed the entry of these new actors and experiences into the commemorative landscape. The first is a burgeoning interest in family history, aided by access to online databases and networks, which can facilitate a more personal encounter with the past and its precious lack of fit with backdated orthodoxy. Second is the greater availability of digitised archives, notably the Bureau of Military History’s witness records from 1913–21 and the Military Service Pensions Collection. Third is a favourable political climate between Ireland and Britain, symbolised by the reciprocal state visits of Queen Elizabeth and President Michael D. Higgins in 2011 and 2014. And fourth is a new body of well-researched and acutely judged works underlining the complexity of the period, often including its international connections.

The focus of these books is variably politics, high or low (Ronan Fanning’s Fatal Path, for instance, and Diarmaid Ferriter’s A Nation and Not a Rabble), the grip of an idea (Charles Townshend’s The Republic), social experience (Maurice Walsh’s Bitter Freedom), or aspects of the rising itself (Ruth Dudley Edwards’s The Seven, Fearghal McGarry’s The Abbey Rebels of 1916, Lucy McDiarmid’s At Home in the Revolution: What Women Said and Did in 1916).

That complexity also draws historians to the kindling and tapering of the revolutionary era, either to “get back before hindsight” (in Roy Foster’s compelling phrase) or to examine the ambivalences of retrospect. Foster’s scintillating book Vivid Faces tracks the multiple passions of the pre-1916 generation and its “culture of pre-revolution” into the 1920s, while the Sydney University scholar Frances Flanagan’s Remembering the Revolution finely maps the psychic undercurrents of the post-upheaval Free State through the work of four critical intellectuals.

The centenary mood benefited from two lucky breaks, one intrinsic and the other extrinsic. The first was that disputes over the commemorative schedule occurred just early enough to be cathartic rather than calamitous. A promotional video released without consultation in November 2014 sparked fury from historians on the advisory group, notably Diarmaid Ferriter. This reductive soup, with history squeezed out by heritage, concentrated minds. Ronan Fanning appropriately warned of the “danger of commemoration”: that “it will propagate a bland, bloodless and bowdlerised hybrid of history” and become a “threat to intellectual honesty.” A rethink upheld the value of historical knowledge, encouraged imaginative and Irish-language projects, and promoted citizenship understood as a bond between past and future. If every school received a copy of the proclamation, it seemed every young person was also invited to dream the twenty-first century republic.

The second piece of fortune was a logjam after the inconclusive national election of 26 February, when voters bruised the Fine Gael–Labour coalition, boosted the Fianna Fáil opposition, nudged ambitious Sinn Féin, and promoted sundry independents. (The latter, along with women candidates, were perhaps “the real winners in 2016,” as Liam Weeks wrote in Inside Story.) But for all this, the result offered no clear prospect of a majority, or even a minority, government.

In the wake, desultory talks involving Fine Gael leader Enda Kenny (by now only “acting” taoiseach, or prime minister) and his Fianna Fáil rival Micheál Martin attempted to solve the perplexing equation of the new 158-seat Dáil Éireann, the lower house of parliament. Yet this political division and cloudiness, far from leaching into the national occasion to come, further elevated it above the fray.

With politicians retreating to the backrooms, the approach of “Easter week” brought a final avalanche of exhibitions, debates, TV features, apps, re-enactments and newspaper supplements. A host of angles included mention of how Australian soldiers on leave in Dublin were hurriedly deployed to help crush the rebels, a theme explored in Jeff Kildea’s Anzacs and Ireland, and of their comrades in London who marched in the inaugural Anzac Day parade, which coincided with the rising’s second day.

There was also a degree of nervousness over potential disruption by extreme nationalist grouplets that claim to “own” the rising’s legacy. In the event, everything aligned on the weekend of 25–28 March: a synchronised array of military parades, ceremonial readings, wreath-layings and dignitaries’ speeches, all covered in depth by RTÉ, which also sponsored the concluding “outdoor history event” in central Dublin. Each of Ireland’s counties had its own packed schedule, most the result of collaboration between councillors, archivists, local historians, and families with links to the events of 1916 in their area. But Dublin’s “sites of memory” – including the Garden of Remembrance, which honours those who fell in the cause of Irish freedom, the GPO itself, and the courtyard of Kilmainham Gaol where the executions were carried out – formed the centrepiece.

This sequence, with its palette of tones, resembled a symphony whose citizen-participants infused each movement, and in the end the whole performance, with extra resonance – not least on Good Friday, when four children, one from each of Ireland’s provinces, laid bouquets of daffodils under the GPO’s portico. Monday brought carnivalesque release. Period costumes, vehicles, posters and stalls made O’Connell Street, the capital’s main thoroughfare, a simulacrum of 1916: today’s Ireland performing a heritage version of itself in the quasi-theatrical spirit that many associate with Easter week itself. (The historian of commemoration, Roisin Higgins, a speaker at that Melbourne conference, says that “the Rising was experienced as an other-worldly event happening parallel to real life” even as it unfolded.)

Later events included the unveiling of a remembrance wall at Glasnevin Cemetery listing the names and affiliations of the 488 people who died in the insurrection and its aftermath: 268 civilians, most of whom were killed by the heavy British shelling or shooting, eighty-four rebels, 119 British soldiers, over twenty of them Irish, and seventeen police, also Irish. Among them are Gerald and Arthur Neilan, brothers from Roscommon, who wore opposite colours. Nearby, demonstrators from a republican group protested the sacrilege of mixing oppressors and martyrs.

Together, all these elements highlight both the novelty of the 2016 commemoration and its political undertow. It was novel not just in the sense that any centenary is a first, but also because the marking of 1916 in earlier decades had established no unambiguous model of how it should be done at all. Its undertow lies in the response of Ireland’s state to the growing influence of Sinn Féin, a political party inseparable from the Irish Republican Army, or IRA.

A month later, on 24 April, the latest episode in this history of contested, or at least negotiated, memory was played out on Dublin’s streets. On this, the rising’s launch date by the secular calendar, Sinn Féin promoted a heritage-style pageant – “Reclaim the Vision of 1916” – which interspersed re-enactments and historical readings with rousing speeches. The title came from a “citizens’ initiative” established in 2015 with the support of some relatives of the 1916 leaders and cultural figures. The previous day, a pro-“dissident”(or anti-IRA) republican offshoot held a much smaller rally.

Sinn Féin’s gathering is part of a separate 1916-related program, expressing the party’s view of itself – and the IRA, now supposedly out of business – as the anointed inheritor of Ireland’s republican tradition. In its weaponised version of history, Sinn Féin has the freehold on modern Ireland’s foundation myth. The legitimacy of the “republican movement” derives from the example of the armed rebels who in any generation have fought for Irish freedom, a struggle that found ultimate democratic sanction in the result of the December 1918 election. That worldview underpins Sinn Féin’s need to reaffirm the eternal verities of 1916 with a festival of its own. More broadly, it also helps explain the party’s consistent and striking disdain towards the actual institutions of the actual Irish republic. In fact, its conception of unconstrained sovereignty is the very image of the British establishment’s. Perhaps that’s a clue to why they can get along so well.

Sinn Féin insiders are skilled in finessing the theological aspects of its doctrine. Many who work or vote for it in good faith do so on account of its conventional radical rhetoric, left-wing nostrums, and popular local campaigners. It has vanquished its rivals in Northern Ireland and is entrenched in government there, where the personable Martin McGuinness has been deputy first minister for nine years. It is the only party with members elected to the parliaments of Dublin, Belfast, London and Brussels/Strasbourg. It is by far Ireland’s richest political party. And it has built extensive support in the south, furthering its aim of being in government in both states as a decisive step towards a united, socialist Ireland.

All this suggests a movement confident and on the rise, which is indeed how Sinn Féin has appeared and been portrayed for several years. But there are downsides, some revealed by February’s election. Its advance in votes (from 9.9 to 13.8 per cent of first preferences in Ireland’s STV/Hare-Clark system) and seats (from fourteen to twenty-three) was modest, its sepulchral leader Gerry Adams proved a drag as much as an asset, and it had the highest unfavourable ratings of any party. That hostility extends to the two leading parties. After the election, they not only ruled out working in coalition with Sinn Féin, but also sought to prevent its becoming the main opposition in the Dáil. (That also foreclosed any prospect of a Fine Gael–Fianna Fáil coalition, an option much discussed though always remote.) In the absence of a new election, a minority government was the last resort. On 29 April, party negotiators reached a three-year “confidence and supply” deal, allowing a new Fine Gael–independent cabinet to coalesce.

This attitude towards Sinn Féin may seem an affront to democracy. But if much in Irish politics is not articulated, nor is it arbitrary. The leading parties share an implicit recognition that in its own mind the “republican movement,” with Sinn Féin as its public face, is less a democratic body than a quasi-state with an armed wing. Ireland’s electoral cycle could yet bring power close to the movement’s grasp – but without fundamental change in its nature, constitutional principle and political logic precludes that.

Ireland’s constitution says: “No military or armed force, other than a military or armed force raised and maintained by Parliament, are raised or maintained for any purpose whatsoever.” That was the undertow of the military parade in Dublin on 26 March. In the words of Micheál Martin, a trenchant opponent of Sinn Féin and the “cult of paramilitarism,” “There is only one Óglaigh na hÉireann.” Can a party that does not fully embrace this reality and continues to venerate the IRA as an “undefeated army” ever be in government in the republic?

There is a “potent fission when politics meet history in Ireland,” writes Roy Foster in his consummate essay “Remembering 1798.” The Sinn Féin dimension excepted, they have been kept conspicuously separate this year. Even during and after the election, which coincided with the approach to the Easter rising’s centenary, recruiting the past for low advantage was given a pass. Much of Ireland seemed to have let history be history and politics go hang.

Anniversaries to come will test that informal pact, and on both sides of the Irish border. Most immediately, the period from 1 July will see many events marking the Great War battle of the Somme, whose many thousands of Ulster Protestant dead enshrined it with a significance that has been curated across decades. An even more cherished date among Northern Ireland’s loyalists is 12 July, when the battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690, long the focal point of their “marching season.” Often during the 1968–98 conflict, its mix of hot weather, alcohol, drums, bonfires and bravado proved combustible.

But much has changed, and there are counter-trends that echo those in the republic, with suitable northern twists. Many Ulster Catholics also fought and died at the Somme, an experience brought into the light by such works as Richard Grayson’s Belfast Boys: How Unionists and Nationalists Fought and Died Together in the First World War. So did Irish soldiers from other parts of that integral island, and for almost two decades they have been honoured in joint Irish-British ceremonies. The annual Boyne memorial in the republic, where the battle site is located, is now an amicable north–south affair. Post-1998 politics and diplomacy have helped leaven attitudes and lower barriers (though Arlene Foster, Northern Ireland’s new first minister, couldn’t go as far as accepting an invitation to attend the 27 March parade in Dublin).

Genealogy and local history are booming in the north, and surveys note a rise in people expressing a “Northern Irish” identity as distinct from a British or Irish one. Government agencies, civic groups and cultural bodies have invested heavily in ensuring a multifaceted centenary, and new academic work addresses the north’s singular character both then and now, and its all-Ireland, British and imperial dimensions. Here, too, more thorough knowledge and a common frame of reference bring new air to the social conversation (if also, in a sectarian polity, the temptations of blandness). As Charles Townshend writes in his classic Easter 1916, “It may never be possible to reconcile the Battle of Dublin with the Battle of the Somme, but both may perhaps be contained by a more capacious understanding of the past.”

Ireland’s politics are very much in transition. In the election, voters put the system on notice. Reform of leading institutions, including both houses of parliament, is overdue. The social impact of the debt crisis remains acutely painful. The new government’s problems include an eruption of vicious warfare between family-crime syndicates, which has claimed twenty lives in 2015–16. Lack of accountability and opportunity drives many to despair, or away.

Most of all, however, Ireland’s leaders are alarmed that the UK – the country’s leading trade and diplomatic partner – might decide in the referendum of 23 June to leave the European Union. If so, the impacts on Irish business and employment, and on relations with Northern Ireland, would be complicating and expensive, and the creation of a new EU land border would seed new insecurities all round.

John Major and Tony Blair made a rare joint appearance in Derry (Londonderry) on 10 June to bolster the anti-Brexit case, echoing concerns already expressed more subtly by Ireland’s government and diplomats. Enda Kenny is visiting three British cities this week to put the message directly. Daniel Mulhall, the engaging London ambassador, points out that common European membership since 1973 has helped make the Ireland–UK relationship one of equals, a status reinforced by the diplomacy of recent decades. “The relationship is now the best that’s ever existed between the two countries. That’s why we’re so worried about [the referendum],” he said on 7 June. That the comment came at a screening of Briona Nic Dhiarmada’s documentary 1916: The Irish Rebellion added to the poignancy.

Amid current uncertainties, Ireland’s honest and large-minded exploration of events a century ago is on track to change the country for good. The commemorative decade might also offer a unique opportunity to turn amity into lasting progress, should the imagination and leadership be found. But if Britain votes to leave the European Union? That would dim the light of this centenary year, divide Ireland further, make a British reckoning with its Irish past even more unlikely, and perhaps cast history into dark reverse. •