Elections are everywhere, but what are they for? The formal language and concepts we use when we think about the machinery of electoral democracy are stunted. They draw on an idea of elections as competitions whose integrity must be managed. Or they look to an ideal of elections as routes to liberal democratic goals like political liberty and equality. In the first case, the analysis is drily quantitative and economic; in the second, it is lofty and normative.

But elections are not abstract instruments. Above all, they are something we experience as citizens. Indeed that is reflected in much of the media attention given to elections – at least the coverage that is not just horse-race treatment of opinion polls. Elections are profound events in the life of every nation, state or locality.

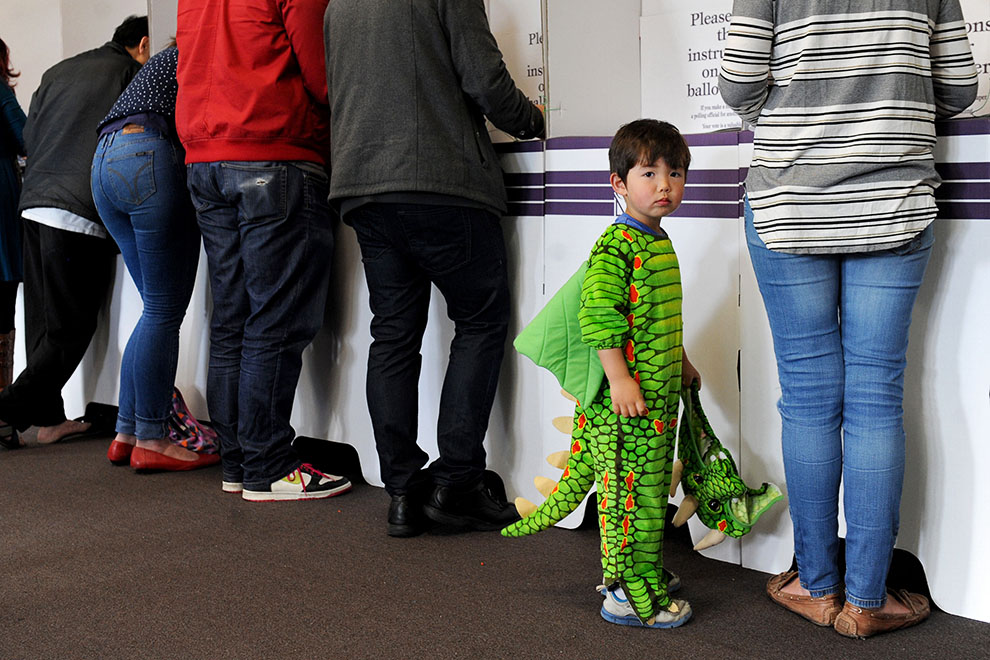

We experience each election as a great ritual, made up of smaller rituals. Those rituals play out through their rhythms: they are patterned, recurring events conveying social meanings, demarked by the parliamentary term. The electoral ritual may be grandiose, as in the summonsing of a parliament or inauguration of a president. Or it can be subtle and everyday, as when the voter retires quietly to cast his or her ballot.

How we run elections encompasses myriad decisions – decisions about how frequently elections are held, about the rhythm of the campaigns, about how much money can lawfully be poured into them. Then there are the communities and communal settings in which we poll. Electoral systems even extend to the social realm and the way people hedge their emotional investment in politics. So we have special rules for alcohol and electioneering (once a problem, then a no-no, now okay) and we regulate betting on elections (once criminalised, now a mini-industry).

Topping it off is the climactic theatre of election night. Britain rushes to declare the result in each electorate in the wee hours of election night – a feat that is only possible because of a simple voting system and an early deadline for postal votes. There is even an informal race to see which declaration can be made first, usually by the local mayor in a town hall with the candidates standing in a row. In Australia, by contrast, all eyes are on the rising tide of data and Antony Green’s computerised modelling of how postal votes and preferences may play out.

That thinking about elections as theatre and ritual might be a fruitful way to understand electoral democracy occurred to me, however dimly, sometime between the ages of six and nine. I recall being taken by my mother to the local polling booth, roughly every year, for a national, state or local poll. We would mingle with neighbours and greet or dodge the party activists who formed a kind of honour guard through which electors passed.

Even – or perhaps especially – as a child, I could sense a restrained excitement among those milling about to vote, or canvassing for votes, before entering the gentler confines of the hall. My mother would let me watch her vote, and even (naughtily, I now realise) let me help her fill in the nether regions of the voluminous Senate ballot.

Afterwards I would look at the how-to-vote cards, discarded in their hundreds, and wonder at the tribalism in the colours of the different political parties, reminiscent of sporting teams. That night, the results would emerge from the national tally room to be broadcast, complete with mock pendulums to illustrate swings. The mathematics was inescapable. Yet this was more than an arithmetical game, as could be seen in the elation or desperation on the faces of candidates and onlookers alike.

“The act of voting has all the glamour of queuing for a wee at a school jumble sale.” So wrote Carol Midgley, columnist for the London Times, on the eve of the 2010 British election. This sounds like a whinge, but Midgley was not complaining. On the contrary, she continued, this “pedestrian ritual is one of the few things in the slick, stage-managed modern election that doesn’t feel fake.” Marking a paper ballot with “something resembling the runty crayon you find at the bottom of your kid’s colouring box,” we were told, feels authentic.

By tradition, we Australians vote in schools, and by law on a Saturday. Schools remain central to the construction of civic identity, emblemising “common responsibility and opportunity” not just through the mandating of years of compulsory education, but also through the curriculum. Civics, literature, social studies, science, art and sport: here lies a hope, or conceit, about the development of the literate, rounded citizen.

School is also central to the transition between childhood and adulthood. It is no coincidence that the franchise begins in most places at eighteen years, just after schooling is designed to end. Leaving school and entering political maturity are two sides of the same rite of passage. Through voting at schools, the rhythm that returns us to the polls every several years reminds us of a bigger rhythm or transition. This is the staged passage of life from the relative coverture of childhood and youth to the responsibilities and rights of adulthood. Chief among these rights and responsibilities, especially symbolically, is the franchise.

But it need not be this way. The United States is a freer but less egalitarian place. Is it any surprise that American citizens vote on a working day, a Tuesday? And, in the scramble to hire venues, that polling places include private businesses and even residences?

There is a shift, too, to “convenience voting,” in Australia and elsewhere. This shift, encouraging people to vote early as of right, threatens the communal experience of polling day. The next step, we are told, is e-voting. Voting from anywhere, anytime. These shifts entail a leap in our understanding of public and political “space.”

Electoral reform agendas too often overlook considerations of ritual. To give a simple example, in my home state of Queensland the Newman government considered banning all canvassing outside polling stations on election day. The discussion was narrow. Would this improve the integrity of the polling place or would it unconstitutionally limit freedom of political speech and demonstration? Yet voting and public behaviour in Australia is not unruly, and last-minute canvassing has little effect on voting outcomes.

The subtler and overlooked question raised by Newman’s plan was the ritual one. Would such a ban leach further colour and life from the most archetypal electoral occasion? Or would it be the ultimate extension of the polling “booth” as a place of repose, a “closet of prayer,” to borrow Les Murray’s poetic description?

In 2000 the US Congressional Quarterly published the first edition of its encyclopaedic Elections A to Z. Its final entry was “Zzz.” This onomatopoeia, used by cartoonists to signify sleep and snoring, was there to symbolise public indifference about electoral democracy. Such a state of alleged lassitude is frequently bemoaned by political commentators and scientists. In itself, such bemoaning is nothing new.

Politics implies anti-politics, and lampooning politicians is just as much a part of the theatre of electoral democracy as any solemnity or ceremony. Those people emblemised by the “Zzz,” however, are neither political animals nor anti-political animals. The “Zzz” emblemises the apolitical: those for whom elections have ceased to matter at all and those who, whether out of trust, contentment or ennui, just leave the system to itself.

Electoral democracy, being representative rather than directly participatory, does much to accommodate that kind of apathy. To those for whom the electoral experience has become meaningless or nugatory, the notion of electoral “ritual” may seem foreign. Whether people welcome elections as colourful times of political focus and renewal, or recoil at the palaver and partisanship, is up to them.

Yet the ritual aspect of electoral democracy should surely be an element in dealing with that kind of disengagement. As political scientist Ron Hirschbein put it, some of that disengagement is attributable to a decline in the affective, and not just the effective, element of modern elections. Disengagement is not simply a product of an instrumental sense that a single vote has little practical effect in a mass electorate. It is also a product of a decline in the subjective experience and “ritual gratification” of electoral democracy. •