Thicker than Water

By Cal Flyn | HarperCollins | $32.99

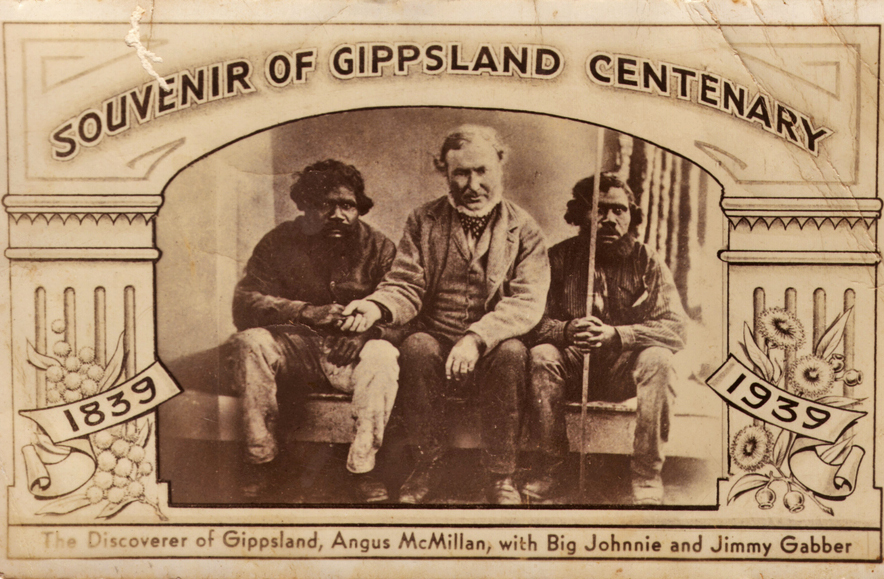

What would make a British journalist drop everything and travel around the world to Gippsland? What propelled her on this journey was an obsession with her great, great, great uncle, Angus McMillan, the squatter who “discovered” Gippsland, and a man regarded by many as a mass murderer of its Gunaikurnai Aboriginal people.

Cal Flyn is a Highland Scot who felt the pull of home at a moment of crisis in her life. There, during a visit to the Isle of Skye, she came across an 1845 map of Gippsland’s squatting runs in an exhibition about the Skye diaspora. It carried a reference to the explorer Angus McMillan. A chance remark by her mother – “he’s a relative of ours” – piqued Flyn’s curiosity and sent her to the archives.

She read McMillan’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography and felt a surge of pride. But what for many amateur genealogists might have been a dream come true was for Flyn the beginning of an angst-ridden struggle to understand the past. That struggle began when the words “Angus McMillan massacres” popped up in her search engine

Much of Thicker than Water is taken up with Flyn’s journey to Gippsland in search of an answer to what she calls her core question: “What could have pushed a man to such extreme behaviour, caused him to slip his moral moorings so completely?” While the research she carried out hasn’t unearthed new material, it is very welcome. Her account of the search for the mysterious “lost white woman of Gippsland,” for instance, brings to readers an important but little-known event that deserves more attention; it was the first great moral panic in colonial Victoria and a disaster for the Gunaikurnai.

Flyn’s strands of historical enquiry are counterposed by a personal anxiety. Does she, as a descendant of McMillan, carry intergenerational blood guilt for the actions of her forebears? Her answer appears to be yes. The book’s title is perfectly chosen.

Angus McMillan has become a polarising figure in Gippsland. For generations he was admired to the point of adulation and no one seemed unduly concerned by his record of violence towards Aboriginal people. Then, thirty years ago, the historian Peter Gardner made the case that McMillan was complicit in massacres. The title of his book, Our Founding Murdering Father, gives you the general idea. Flyn’s account of McMillan draws heavily on Gardner, and is just as tendentious. My main criticism of Thicker than Water is that it simplifies the evidence against McMillan, and presents this in a way that denies readers the opportunity to decide for themselves.

It also contains curious omissions. Flyn doesn’t mention the one primary source tending to confirm speculation about McMillan’s participation in the frontier violence. In 1858, his friend Caroline Dexter wrote that McMillan was “compelled, in his early days, to destroy numbers of more treacherous natives.” This is an important revelation, and it came to light only recently (for the details, see Patrick Morgan’s book Folie à Deux: Caroline and William Dexter in Colonial Australia). In my view, Dexter’s source was McMillan himself, but what still isn’t clear is whether McMillan was referring to the tit-for-tat skirmishes he describes in his own recollections, or admitting to something that had previously been off the record. In particular, is he alluding to an event that has come to be known as the Warrigal Creek massacre?

Somewhere near Port Albert in 1843, Aboriginal tribesmen ambushed and killed a man named Ronald Macalister. This Macalister was the nephew of Lachlan Macalister, an uber squatter who bankrolled the exploration of Gippsland. The elder Macalister was a captain in the NSW border police, and an experienced hand in the violent suppression of Aboriginal resistance. In reprisal for Ronald’s death, settlers tracked down a group of Gunaikurnai camped near a waterhole, most likely at Warrigal Creek near Woodside, and killed a large number of men, women and children using firearms and possibly tomahawks.

Flyn presents McMillan’s leadership of the attack at Warrigal Creek as a fact, and her book begins with a dramatisation of the event. She makes some vague comments about sources in the Author’s Note, but you won’t be able to go to a library and use the book to check on any of this. A reader would not know, for example, that no firsthand accounts of the Warrigal Creek massacre exist, and that Flyn’s information comes from two secondary sources, both of which appeared decades later. One version is contained in George Dunderdale’s The Book of the Bush (1898) and names Lachlan Macalister as the leader of the reprisal. Dunderdale doesn’t mention McMillan in connection with the events following Ronald Macalister’s death, although he does appear elsewhere in the book.

The second source is an article published in The Gap magazine of 1925 by a writer under the pseudonym “Gippslander.” “Gippslander” was William Hoddinott, whose father held the Warrigal Creek run at the time. Hoddinott claims to have known two of the survivors. One was a boy, shot in the eye, who was forced to lead the attackers to other camps. The other was a man who managed to swim away.

This is the key piece of evidence linking McMillan to Warrigal Creek, but I wonder if Flyn has read the original text. All it says directly about McMillan is that he was the discoverer of Macalister’s body. The perpetrators are named as “every man who could find a gun and a horse” and there is no mention of anyone leading the attack.

A third source much closer to the event also confirms that violence broke out after the killing of Macalister. It is a young squatter named Henry Howard Meyrick. In my reading about William Thomas, an assistant protector of Aborigines, I came across a record of a meeting with Meyrick, which Thomas’s journal records as taking place early in 1846. Meyrick is recorded describing the “awful sacrifice of life after the murder of Mr Macalister” and then referring to “a reported Act of a Scotchman who went out with a party Scowering, not to be credited by one who calls himself a Christian.” Again no names are given. Who was the “Scotchman”?

Another Scot on the Gippsland frontier may deserve more attention than he has previously received. Frederick Taylor, a Lowland Scot born in Forfarshire, is not mentioned in Flyn’s book, and rates little mention in other accounts. In 1836, he tied an Aboriginal man to a tree and left him under the supervision of a convict servant called Whitehead, who shot the man dead. Whitehead was tried for murder and acquitted; police magistrate Willian Lonsdale “entertained a strong suspicion that he [Taylor] had given strong encouragement to the prisoner to commit the murder.”

In 1839 Taylor was overseer on a new squatting run, Strathdownie, near Lake Corangamite in Victoria’s Western District. Without provocation and with little assistance, he wiped out almost the entire Tarnbeere Gundidj clan of the Djargurd Wurrung. In what is known as the Murdering Gully massacre, around thirty people were shot dead when Taylor led an attack on their camp under cover of darkness. Other stockmen were shocked by the extremity of the act, and the details are confirmed by multiple firsthand accounts. Rather than face questioning, Taylor fled to India.

Taylor resurfaced in 1842 – in Gippsland. His presence came to the attention of the superintendent of Port Phillip, Charles Latrobe, and, through him, Governor Gipps in Sydney. Taylor’s homicidal history was known to the authorities, and Gipps ruled that Taylor was not to hold a squatting licence or supervise a run in Gippsland. In other words, Taylor was too great a risk to be given unrestrained access to Aboriginal people in the back blocks of 1840s Gippsland. Ultimately, these efforts – effectively an attempt to drive him out of the province – failed when Charles Tyers, the local crown commissioner for land, backed down on the ban. Gipps was infuriated. (I have recently transcribed the correspondence relating to the episode; it makes a fascinating case study of the limits of executive power in the governance of the colonial frontier.) Taylor’s behaviour was shocking in other ways. During a trip over the Alps in winter, he made his Indian employees sleep in the snow while the whites sheltered in tents.

The allegations against Angus McMillan are of the utmost seriousness, but there is no evidence that he was a gratuitously cruel man. In fact, Flyn discovers, as have many of us who have gone searching, that the McMillan of the 1850s and 60s was in many respects an admirable person who showed concern, in his own way, for Aboriginal welfare. This is what makes him such an interesting and infuriating figure to study. Life would be easier if we could just write him off as an utter villain.

One of the thorny problems in making moral judgements about the past is that good people could say and do things we find appalling. Henry Meyrick was willing to call out “complete murder” when he saw it. He died young, drowned while swimming across the Thomson River seeking help for a woman who was dying in childbirth. He was a good and humane man in anyone’s book. And yet he was capable of saying, “If I caught a black actually killing my sheep, I would shoot him as I would a wild dog.”

In my own journey of reading Gippsland, I have struggled with the question of where McMillan stands on the spectrums of decency and violence. The extent, nature and context of the latter does matter. Frederick Taylor would have made a fine conquistador, but we should be grateful that not all squatters were of his ilk. Was Angus McMillan such a man? Flyn is certain that he was. I’m really not sure.

For all the polemic about which squatter did what, the 1840s were years of bloody catastrophe for the Gunaikurnai, whose numbers were massively reduced by disease and violence. Thicker than Water is an important contribution to public understanding about this period, and Flyn’s compassion for Indigenous Australians is manifest throughout. But if I could recommend one text for all Australians to read about the fall of Ancient Gippsland, it wouldn’t be this book, or Peter Gardner’s writings, or even Don Watson’s masterpiece, Caledonia Australis. It would be Alfred Howitt’s introduction (pages 181–88) to his contribution to Kamilaroi and Kurnai, published in 1880, where the tragedy of the Gunaikurnai is captured in a few pages of deeply humane prose, leaving little else significant to say. •